This article originally appeared on The Atlantic.

In recent years, Raj Chetty has become economist-famous for cataloging American inequality, assembling enormous data sets showing which Americans tend to get ahead. More to the point, his work show where Americans tend to get ahead. Chetty, a Harvard economics professor, has focused on how where one grows up shapes one’s economic prospects.

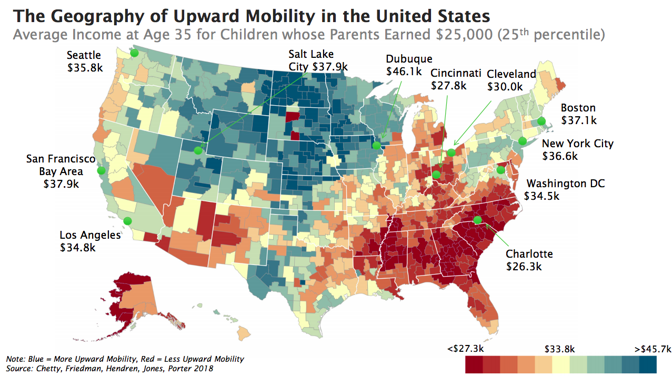

Chetty’s research demonstrates just how unevenly “upward mobility”—basically, people’s ability to earn more money than their parents did—is dispersed throughout the country. The following visual, for instance, shows the average earnings at age 35 of people raised in various regions to parents who were in the 25th percentile of income; the areas shaded in blue offer more upward mobility to children born there, while the areas shaded in red offer less.

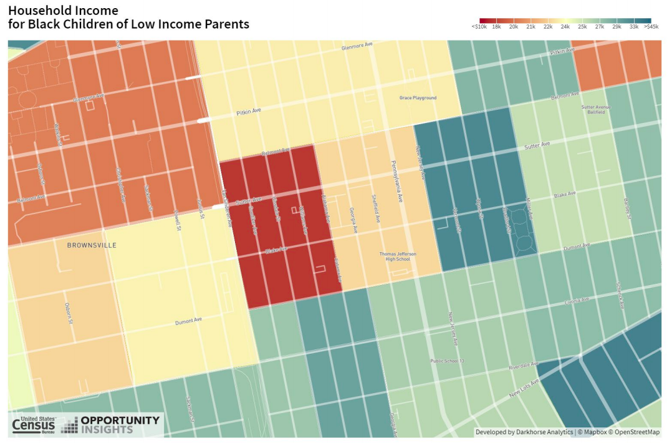

But Chetty and his research collaborators have gotten much more granular than that. Those same reds and blues, it turns out, exist on the level of the city block. Consider the large disparities in average earnings for people born into low-income black families and raised in different, but nearby, parts of Brooklyn’s Brownsville neighborhood. (Each rectangle represents a city block.)

Huge gaps in economic prospects, in other words, frequently exist across very short distances. And it’s a bit jarring just how short those distances can be. “Poverty rates that are more than about half a mile away from your house are essentially completely irrelevant in predicting your own outcomes,” Chetty told an audience at the Aspen Ideas Festival, co-hosted by the Aspen Institute and The Atlantic. Which is to say, a high rate of poverty in the area immediately surrounding one’s home can be stifling, even if a “higher opportunity” neighborhood with great schools is only a short distance away.

Chetty said that this half-mile figure can be viewed as both encouraging and discouraging. It’s discouraging in the sense that a straightforward, one-size-fits-all nationwide policy would be unlikely to address neighborhood-specific disparities—something more locally tailored is probably in order.

But it’s encouraging in the sense that “we don’t need to look at a different country or a different time period to figure out how we would get to a situation with higher upward mobility,” he said. “Often, we can just look a mile down the street, or a couple miles down the street … It shows that we’re not trying to achieve something unimaginable.”“I don’t view the half-mile radius as some structural fact about the world that will never change,” Chetty went on. “I think that’s partially a result of the highly segregated nature of American cities. Things tend to be very clumped … and it need not be that way.”Chetty is currently doing research on how these patterns might be undone. In one promising experimental program—the results of which will be released in a month—he and other researchers have teamed up with housing authorities in the Seattle area, helping low-income families move to higher-opportunity neighborhoods, if they want to.

The theory behind the program—which is targeted toward families who get off the wait list for housing vouchers—is that many of these families might want to move to a new neighborhood but face barriers to doing so. So the program provides ways of potentially eliminating those barriers—for instance, participating families can take tours of unfamiliar neighborhoods and receive money to be put toward moving costs or a security deposit they otherwise couldn’t afford.

“Of the various things I’ve studied over many, many years, this turns out to be one of the highest-impact, most successful things I’ve seen,” Chetty said. “We’ve dramatically changed where families choose to live. Where previously it was a small fraction of families moving to high-opportunity areas, now the majority of families are choosing to live in high-opportunity areas.” With programs like this, the composition of American cities could, with any luck, gradually start to change.