One in ten workers in the U.S. work outside of permanent, full-time employment. More than half of these are independent contractors, without an employer obligated to provide them workplace benefits and protections. As risk has shifted increasingly onto workers in our modern economy, these independent workers have received greater attention from policymakers, researchers, and labor advocates. California has been at the forefront of these conversations: Silicon Valley has cultivated platform companies that rely on independent contractors to perform a wide range of tasks; Hollywood has long brought together independent artists and tradespersons; and the state is home to more independent agricultural workers than any other.

California also has a history of labor movement leadership. It was one of the first states with a minimum wage, it gave birth to the agricultural labor movement, and, last month, it passed one of the nation’s first laws intended to extend the benefits and protections of employment to gig economy workers. California’s Assembly Bill 5 (AB5) redefines employment across the state and has brought significant national attention to the issue of worker classification in today’s economy. This post provides some background on worker classification in the U.S., explains what California’s new law does and does not do, and highlights some areas for continued policy innovation to ensure work provides dignity and security in the 21st century.

Worker Classification in the U.S.

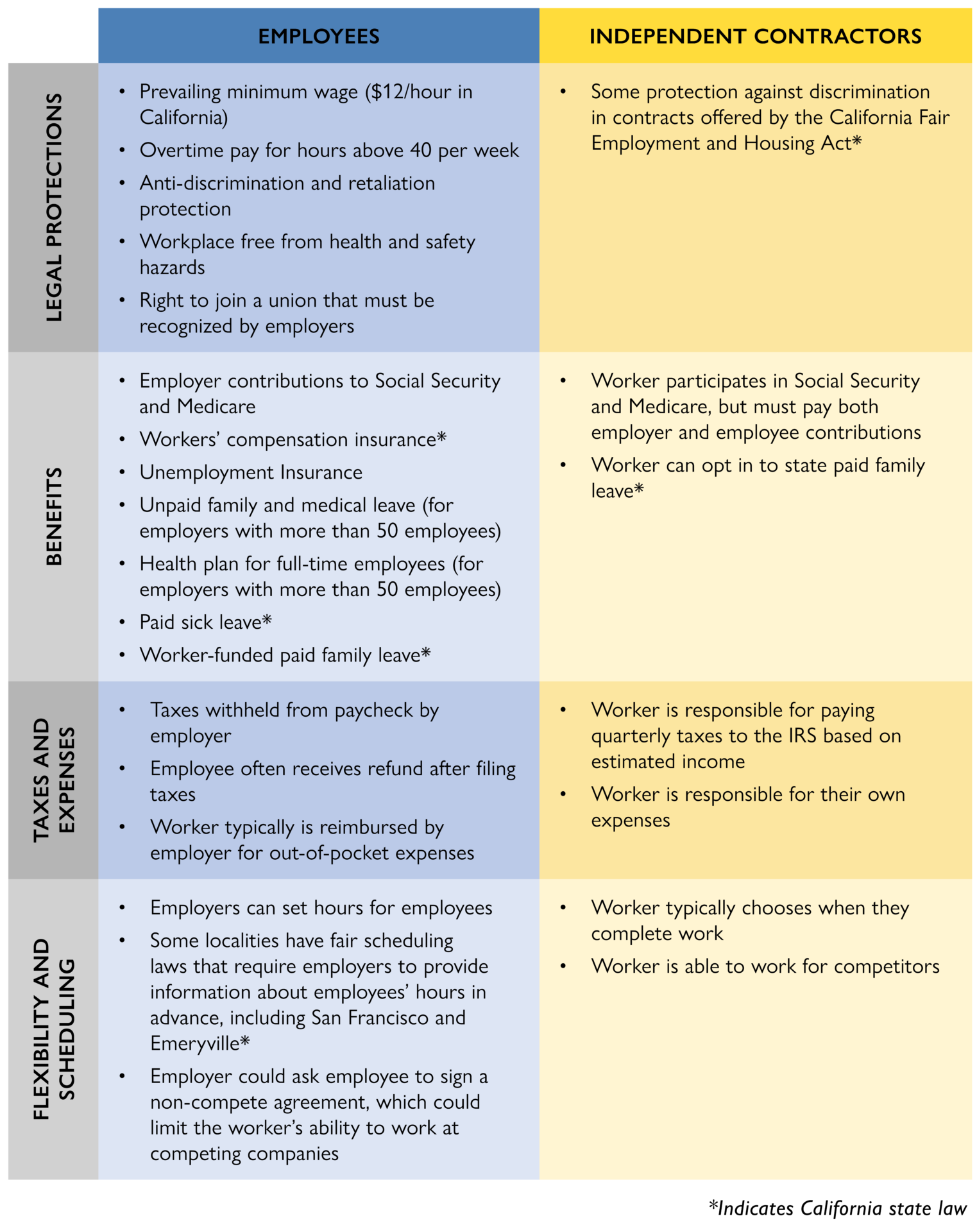

In the U.S., companies hire workers as either employees or independent contractors—and there are major implications of this classification for both workers and businesses. Typically, employees are hired to work directly for a company part- or full-time and are covered by federal and state labor laws, which mandate that employers provide and pay for a range of benefits and protections, including but not limited to a minimum wage, Unemployment Insurance, workers’ compensation insurance, employer contributions to Social Security and Medicare. Independent contractors, often hired to perform discrete services or projects, are not covered by these laws, and typically have a greater degree of control over the way they charge for and complete their work.

There is not one set of criteria used across the U.S. for determining if a worker is an employee or independent contractor. Instead, different agencies at different levels of government offer different sets of criteria, resulting in a complex and at times inconsistent landscape. At the federal level, the National Labor Relations Board, the Department of Labor, and the IRS all offer guidance. In states, wage boards, state departments of revenue, workers’ compensation offices, and Unemployment Insurance programs can each apply their own criteria. Although all criteria speak in some way to the degree of control a company has over workers’ labor, there is wide variation in the clarity and strictness of different tests. They range from a 20-factor test formerly used by the IRS that still applies in some states, to a 3-factor test, often called an “ABC” test, that is commonly used by states to determine Unemployment Insurance eligibility. One work arrangement can be subject to different tests across state and federal agencies, and could be found by courts to be considered an employee under one test, but an independent contractor under another.

California’s recent legislation is one attempt to simplify this complicated landscape. Since a state Supreme Court case in 1989 dealing with the classification of cucumber harvesters, S. G. Borello & Sons, Inc. v. Department of Industrial Relations, California’s Industrial Welfare Commission, the entity responsible for enforcing wage and hour laws, had used an 11-factor test when deciding if workers were employees or independent contractors. In 2005, a delivery driver for the company Dynamex filed a complaint that he and others had been misclassified as independent contractors, which eventually became a class action case in the state’s Supreme Court, Dynamex Operations West Inc. v. Superior Court. In its decision, the court applied an “ABC” test for the first time in California. Under this test, a worker was more likely to be found an employee, and the court agreed that the delivery drivers had been misclassified as independent contractors.

Under the test laid out in the Dynamex decision, workers are assumed to be employees, and companies must meet each of three criteria in order to prove their workers are legally independent contractors:

- The worker must be free from control and direction;

- The worker must perform work outside the usual course of business of the company; and

- The worker must be engaged in an independently established trade or business

These criteria were similar to those used in a number of offices around the country, including many Unemployment Insurance offices, Massachusetts’ wage and hour laws, and within particular industries in a handful of states. Although setting an important precedent in California, the Dynamex case itself, settled in May 2018, did not bring widespread change. Workers who felt they had been similarly misclassified still had to bring their claims to court.

Introduced in December 2018, California’s Assembly Bill 5, abbreviated AB5, codifies the ABC test used in the Dynamex case into law, meaning that companies would have to prove workers met each of the three criteria in order to be legally classified as independent contractors and not covered by state wage and hour laws. Introduced by Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez of San Diego, it passed the Assembly in May and the state Senate on September 10, before being signed into law by Governor Gavin Newsom on September 18.

Although much of the conversation about the bill has centered on rideshare and online platform workers, there are more than 2 million independent contractors in the state, most concentrated in construction and in service professions ranging from medical providers to janitors. AB5’s ABC test will not apply to all of these workers; the law includes exemptions for a range occupations, including real estate agents, doctors, architects, cosmetologists, dog groomers, lawyers, and engineers. Most of these exemptions were granted on the basis that workers in these occupations typically set their own rates, communicate directly with their own customers, and make at least twice the minimum wage. Industry lobbyists argued the stricter test would limit economic activity in the state. In exempt occupations, the previously used 11-factor Borello test will be used for classification decisions. Several online platform companies, including Uber, Lyft and Postmates, pushed for an exemption of their own. In the weeks leading up to the final vote, they discussed a proposal with policymakers and labor advocates in which they offered a wage floor, a benefit fund, and a recognized worker organization along with their proposed exemption.

Although the law will take effect at the start of 2020, it will not automatically change work arrangements, and thousands of workers will not suddenly begin receiving the benefits of employment. Instead, they must be reclassified by employers. If workers believe that they have been misclassified under the new test, they can pursue legal action. In addition, the state can take action against companies it considers to misclassify workers. Willful misclassification of workers as independent contractors is a violation of California labor code, and the law has a specific provision allowing the state Attorney General or city attorneys to seek an injunction against companies they believe to be in violation. Uber has announced that it plans to continue to classify drivers as independent contractors, asserting that they are a technology company, and driving is outside their usual course of business. In addition, rideshare drivers typically agree to arbitration clauses when they sign up, requiring them to settle disputes out of court and preventing class-action cases.

Employee Status Ensures Range of Benefits and Protections

Being classified as an employee guarantees a worker a range of benefits and protections that are not offered to independent contractors, summarized in the chart below.

As the chart shows, being classified as employees ensures workers a range of benefits and protections. Platform companies have often cited flexibility as a key advantage of independent contracting for workers. Although companies have a greater ability to set schedules for employees than for independent contractors, there is no requirement that this be the case, so the employees’ flexibility is at the discretion of the employer. Several companies have developed flexible scheduling options for short-term and task-based employees, including Hello Alfred, an at-home services provider, Eaze, a California-based on-demand cannabis delivery company, and Spin, a scooter sharing company owned by Ford. These companies allow workers to sign up for shifts and tasks based on their needs and availability. Despite the legal framework, the additional costs of hiring workers as employees instead of independent contractors may lead companies to impose limitations, such as limiting the number of workers active at a given time, or limiting hours to prevent full-time employment (and therefore mandated health insurance coverage) or overtime payments.

Work Still to be Done

AB5 is likely to lead to more workers being classified as employees, and therefore to increase those workers’ access to the benefits and protections described above. There is still room for further policy innovation in California and beyond in order to address the needs of precarious workers in today’s economy.

There are millions of workers classified as employees who struggle to access key benefits, living wages, and stable jobs. 27 percent do not receive any paid sick time. 45 percent do not participate in an employer-provided health plan. 48 percent do not have employer-provided retirement benefits. 82 percent have no paid family leave, and 90 percent receive no childcare assistance. Temp-agency, on-call, and subcontracted employees are particularly unlikely to access benefits through their employer.

As argued in the Future of Work Initiative’s recent publication, Designing Portable Benefits: A Resource Guide for Policymakers, portable benefits policies can help address this challenge and ensure that work can provide financial security and a sense of stability for everyone in America. Portable benefits are those that are attached to a worker, rather than to a particular job, allow for contributions from multiple parties, including multiple employers, and are available to all workers. If workers are in part-time arrangements, they can receive proportional contributions to social insurance programs, and if they hold multiple jobs, benefits contributions can be combined. Social Security is an example, facilitating contributions from workers as well as multiple employers, sequentially and simultaneously. Several states have implemented paid leave and retirement programs that follow this model. Recognizing the importance of both clarifying classification and improving benefits coverage among workers, Washington state Representative Monica Stonier proposed legislation last session that combined a new portable benefits program with an ABC test for classification, a model others may consider to comprehensively address workers’ needs today.

In addition to expanding benefits, policymakers seeking to further the goals of AB5 need to consider how to strengthen worker voice—and due to recent federal action, platform workers may require particular focus. Among the protections that come with employee status, the right to organize, guaranteed by the federal National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), is particularly important, because it equips workers to fight for additional rights and to ensure their current protections are enforced. But platform workers, even if reclassified as employees, do not have this right. In May, the National Labor Relations Board, which oversees the NLRA, wrote that it would not enforce the NLRA against these workers. One proposal that can ensure the right to organize and collectively bargain is available to more workers is sectoral bargaining, in which workers across businesses in a given industry organize to collectively bargain with employers of that industry on a wide range of issues—an idea that has gained support from the California Governor’s office, the labor movement, and rideshare companies. A benefit of this approach is that it reduces any competitive disadvantage a company may face if its workers unionize, since bargained-for standards apply to all workers at all companies in the industry. Sectoral bargaining could also bring the right to organize and collectively bargain to workers left out of the National Labor Relations Act, including domestic and agricultural workers and independent contractors.

As policymakers consider ways to expand workplace benefits and protections, they also need to keep in mind the broader economy. Beyond the issue of classification, our economy is not working for many; wages for low- and middle-income earners are stagnant, families struggle to meet unexpected expenses, and increasing numbers of workers are taking on supplemental work to make ends meet. This includes the majority of platform workers, who work sporadically to supplement other income sources. Structural change can and must address these problems over time, improving the quality of jobs and reducing the need for supplementary income. However, in the immediate future, thousands of workers need job opportunities with low barriers to entry that enable them to earn extra income when it is needed. If AB5 impacts the availability of these earning opportunities, it may focus policymakers on the long-term changes needed to address the underlying problems mentioned above, but may also temporarily exacerbate financial insecurity for people who depend on platform work in America.

While there’s more work to be done, AB5 is a significant piece of legislation for the so-called gig economy and beyond. It seeks to clarify the incredibly complex and muddled arena of employment classification and expand the number of workers who access benefits and protections through employment. Yet it is not a quick or complete solution. The inclusion of specific exemptions and its coexistence with other criteria of classification both within and beyond California mean that policymakers, workers, and employers will continue to navigate its implications in the coming months and years ahead. Building on this recent legislation, labor advocates and employers have a great opportunity to develop complementary approaches to renew the promise of work in the 21st century.