Let me tell you a story about Kobe Bryant that has not been shared before. It’s one that speaks, I think, to the true character of the man we just lost, all of us, in ways that can only be fully appreciated when a force of enormous creativity, drive and purpose comes to rest – and there is no more inertia, just waves of impact washing over us, each bigger than we anticipated at the start of the day.

Last August, we launched a major public awareness campaign called Don’t Retire, Kid. By we, I mean Project Play, our Aspen Institute initiative that aims to build healthy communities through sports with the help of many organizations that touch the lives of kids.

You may have seen the lead PSA. A 9-year-old boy announces at a press conference that he is “retiring from sports” because the adults have gone haywire. He got into this to have fun with his friends, and … well, you know the rest. Kobe needed to like the spot because he was going to launch the campaign for us, pro bono, on social media and ESPN.

“What do you think?” I asked him, in a room at ESPN’s LA studios.

“It’s OK,” he said, curtly, lips pursing with that familiar intensity.

Of the four languages Kobe spoke, body language was his loudest.

He wasn’t happy, and, having talked with him about the campaign for nearly a year, I knew why – the Mamba wanted a more aggressive script. He didn’t just want to wake up sports parents to the undue pressures they are putting on kids to perform. He wanted to punch them in the nose, these adults, many of whom were surely his fans.

Now, mind you, the script was already pretty direct. The truth it put on the table was uncomfortable, that we’re screwing it up for the next generation and that all of us – leagues, media, tech, athletes, coaches, schools, colleges and policymakers – need to be better stewards of the institution of youth sports. When the average kid quits sports by age 11, as our research shows, we collectively have a systemic problem.

As a trained journalist with a long history of trying to push truth into the jockosphere, I was thrilled that ESPN was prepared to run the spot hundreds, if not thousands, of times in the coming months.

Kobe wanted more edge, because to him it was personal. The first time we had lunch about Project Play, two years earlier, he told me about a game in which he was coaching his daughter Gianna’s team. The opposing coach was screaming at his players, berating them for mistakes. This went on the whole game, Kobe’s temper growing. He knew from being coached well that this isn’t coaching well. And he hated to see the girls on that team suffer from the emotional abuse.

During post-game handshakes, Kobe told me, he stopped the coach, looked directly into his eyes and, with the same quiet if intense fury once directed at NBA rivals – he demonstrated this for me – said, If you EVER act like that in another game in which I am coaching, you are going to have to deal with me. And trust me, you don’t want that.

At that moment, I knew Kobe was sincere about our project. I had never heard an athlete talk with such passion about sticking up for kids. Or ask as many sophisticated questions about our work.

“How do you approach the debate around participation trophies?”

“How do you mobilize organizations to change the game?”

“How do you tell your stories?”

Most pro athletes are one-way streets. You ask, they tell. Comes with the territory, a lifetime of being put on a pedestal in which you are treated as the center of the universe and nothing is as interesting as you. Here, in Kobe, I had one of the world’s true sports icons being curious about realms well beyond the arena, committed to learning, unafraid of the unchartered, and offering to give voice to the voiceless.

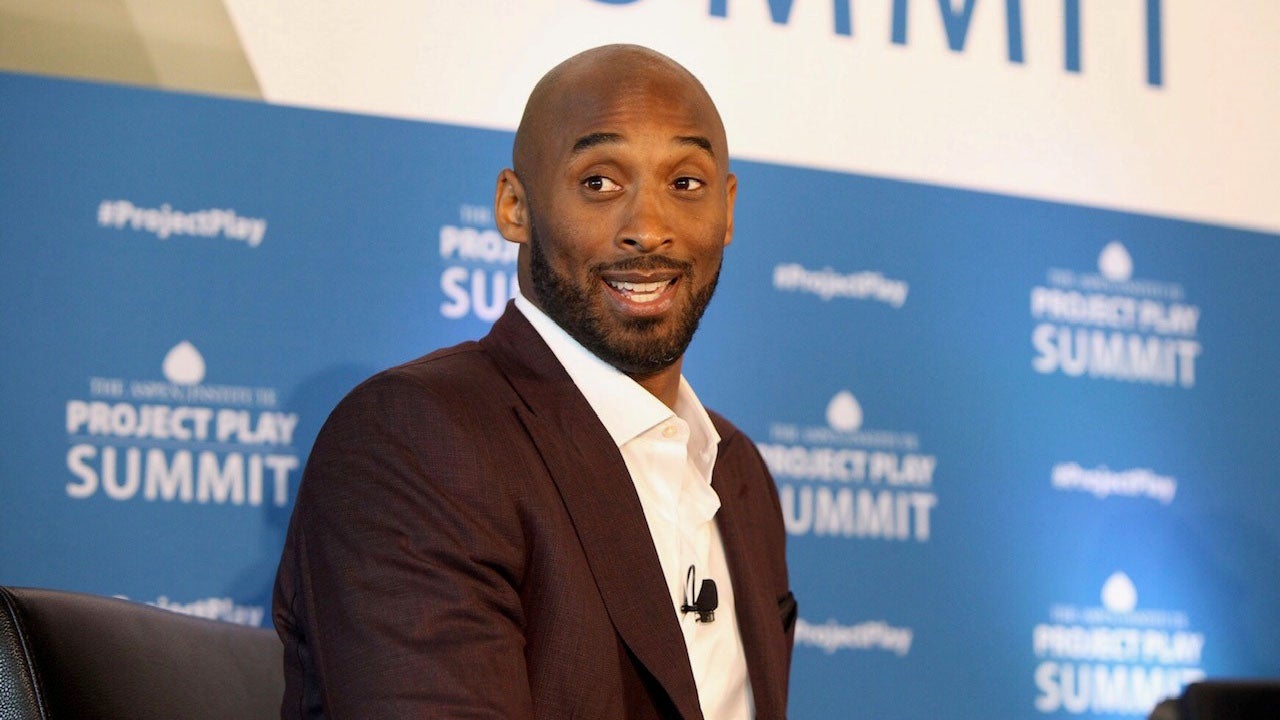

I didn’t have to sell him on anything. He was just in, eager to deploy his assets – his champion’s credibility, his social network, his advocacy, his international reach – to improve an institution that impacts the lives of youth. We chose Arnold Worldwide, the Boston-based agency that built Don’t Retire, Kid, based on his recommendation and that of his deft marketing chief, Molly Carter. Kobe moderated a panel with children at our Project Play Summit, to help tease out what kids want from a sports experience. For our Healthy Sport Index, he supplied a list of companion sports that basketball players can use to build skills and health (he also suggested meditation, to focus the mind).

My favorite athlete as a child was Roberto Clemente, for the style in which he played and his obvious care for others. His 1972 death from a plane crash while on a humanitarian mission left a hole in our hearts but opened up something to be filled as well by citizen-athletes, like Kobe using the modern tools of social change.

I learned of his passing shortly before I boarded a flight in Washington D.C, just as I was about to call my youngest child, Kellen, the boy holding a basketball aloft on the cover of my book, Game On: The All-American Race to Make Champions of Our Children. He’s 16 now, a soccer athlete who hasn’t played organized hoops since middle school but like his big brother Cole has always admired Kobe above all athletes. I apologized by text that I couldn’t call, with all the news coming in. He texted me back:

No problem, I have been reflecting on the impact he (Kobe) had on my life. His work ethic, determination, and what he did to give back to society. He was more than a basketball player to me and his legacy will forever live on. Hope you are doing well with this and we can talk later. Love Kellen.

With that, I cried so hard one of the contacts in my eyes fell out. I didn’t know that was possible. We learn something new every day. Including: Money isn’t the only way an athlete can change the world. LeBron represents the gold standard when it comes to athletes deploying dollars for good, and God bless him – we need more like him. Kobe donated in places too, but he also knew his lane. He sought culture change, building on the foundation, established over a long NBA career with just one team, of the personal characteristics he embodied.

He wasn’t perfect. He flashed ego and made errors that altered his life and that of others. A friend of mine likened him to Our Lady Di, flawed but beloved. But the better angels of his nature carried the day.

“Sport is the vehicle through which we change the world,” Kobe said in my interview with him in 2018. “The next generation is going to carry this world forward.”

That he died while traveling by helicopter to a youth basketball game, with his daughter and others he brought along for the ride, is not ironic. It is consistent with what he cared about: fatherhood, imagination, and youth sports as a tool of human development. My heart breaks at the horror he must have felt in those final moments, knowing the life of his child might end right there, at age 13, with no chance to flower further.

I am also sad for everything that lay ahead for Kobe, who at 41 was just getting started on his post-life mission. He was laying the groundwork to push so much good into the world, through his books, podcasts and other projects aimed at children. He had more to give Project Play. As a major donor to the construction of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, he was granted one free lifetime use of the facility. He offered that to us, for our annual Summit.

We will gather at a different venue in Washington D.C. this October, at a space and date to be announced in the coming weeks. And when we do, he will be appreciated. Not just for his contributions to Don’t Retire, Kid, now up for several international awards. Or the advice he shared with parents on our platforms. But for building a life that helped build that of others. For being an original, in service of the future.

“Dream Big, Live Epic,” he scrawled on one of our Summit boards.

Now it’s up to us to be as impatient as he was with progress.

Tom Farrey (@tomfarrey) is executive director of the Aspen Institute’s Sports & Society Program (@AspenInstSports), and a former ESPN journalist. Watch videos and learn about Kobe Bryant’s perspectives on youth sports, as well as other contributions to Project Play, here.