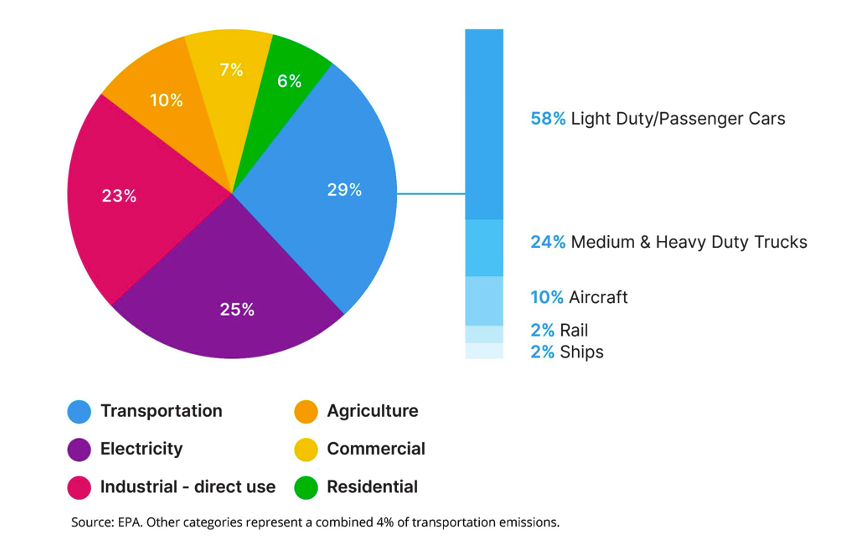

As the world prepares for the UN Climate Change Conference this November, policymakers are exploring strategies to help us reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The United States has made progress in greening our electricity grid, with the majority of new generation capacity installed over the past decade coming from renewable sources such as wind and solar. However, emissions from the transportation sector continue to grow and now represent 29% of total US emissions—more than any other sector. In the coming months, the Aspen Institute Energy & Environment Program will explore pathways for decarbonizing transportation including passenger travel and freight movement.

In this post, we focus on local passenger travel. The majority of passenger vehicle trips in the US are five miles or fewer, and passenger travel represents a significant share of transportation emissions. Solving this piece of the puzzle will be critical to achieving the Biden-Harris Administration’s goal of a 50% reduction in the nation’s GHG emissions by 2030. Below, we offer a three-part framework for decarbonizing local passenger travel.

I. Designing the built environment to reduce the need for motorized travel

Our daily travel patterns are determined in large part by the shapes of our cities and rural areas. A range of land-use policies and strategies are available to shape the built environment more sustainably. For example, we can encourage walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods where residents can reach many of their day-to-day needs without a car. One such strategy is transit-oriented development (TOD): locating new residential, office, and retail development at or near transit hubs.

TOD can transform underutilized land into homes and recreational spaces that spur economic development while giving residents better options for convenient and affordable mobility. The San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District (BART) has already built more than 2,000 housing units and nearly one million square feet of office and retail space on land formerly used for parking at rail stations, with many more TOD projects planned or under construction.

Many cities and states are revising or even eliminating long-held building codes, such as parking minimums, to support sustainable land use. Parking mandates inhibit density and raise housing costs, requiring all buildings to maintain a certain ratio of parking spaces per residential or retail unit. As a result, land that could be used to house people is instead reserved for housing cars—whether or not residents want them. As cities gradually pivot away from a car-first orientation, these land-use strategies will play a key role in reducing carbon emissions while creating more livable communities.

II. Shifting travel onto public transportation

Of course, the goal of transportation policy should not be to eliminate all vehicle travel. Rather, we should give people more options to get where they need to go safely, reliably, affordably, and sustainably. For most of the last century, federal and state transportation funding has focused on building highways that allow for convenient travel in private cars, while investing much less in public transportation. As a result, fewer than 5% of Americans use public transit to commute to work—a number far lower than in most other OECD countries.

To bend the curve on our transportation-related GHG emissions, we need to increase funding for transit, correct hidden subsidies that encourage private vehicle use, and encourage innovation in shared mobility. In many cases that will mean investing in high-volume fixed-route transit services such as commuter rail, light rail, and bus rapid transit, along with reliable local bus services. In other cases, like in lower-density areas or during off-peak hours, dynamically routed on-demand transit can offer a flexible and rapidly deployable solution to expand access or improve service quality and efficiency. And increasingly, transit agencies are turning to bike, scooter, and microtransit services to improve first- and last-mile connections to fixed-route transit.

III. Electrifying our fleets

By building more walkable communities and shifting more trips from cars to public transit, we can reduce the total number of vehicle miles traveled (VMT) on our roads—a key metric for transportation decarbonization. The final piece of the puzzle involves vehicle technology, and ensuring that as many as possible of the VMT we travel are taken in low-emission vehicles.

We have made considerable progress in this area. In 2010, fewer than 17,000 electric vehicles (EVs) existed around the world. Today, we are putting about 17,000 new EVs on the world’s roads every day. But we’ve got a long way to go. Battery electric vehicles make up less than 1% of all light-duty vehicles in the US and an even smaller fraction of heavier vehicles like trucks and buses. To further electrify our fleets, we need to ramp up investment in alternative vehicle technology research, development, and deployment. And just as important as the vehicles is the investment in the infrastructure needed to power the vehicles of the future—including an expanded network of EV charging stations and the electric grid infrastructure needed to supply power to those charging stations. It could also include other alternative fuel infrastructure such as green hydrogen distribution networks.

Equity and funding the transition

Beyond their climate impacts, the investments outlined above are critical to advancing equity and economic mobility. Transportation is the second-largest expenditure category for US families, and the average cost of car ownership is equivalent to 20% of US median income. Moreover, in some metro areas, individuals with a car can access almost 30 times as many job opportunities as those who rely on public transportation. Public transportation services are essential to ensuring that everyone can access jobs, schools, medical appointments, and other resources, regardless of their economic means or physical abilities. A more sustainable transportation system would also help reduce emissions of particulate matter and other local pollutants that lead to a range of health problems and disproportionately impact low-income communities and people of color.

A range of options exists to fund the transition to cleaner transportation networks. Policies like an economy-wide carbon tax or cap-and-trade system could generate significant revenue for investments in infrastructure while eliminating hidden subsidies for carbon-intensive modes of travel. Many cities are now considering congestion pricing programs that assess a charge for driving private vehicles into heavily trafficked urban centers. New York City plans to introduce a new fee next year that would initially fund up to $15 billion of investments in transit improvements. European countries have used a range of carrots and sticks to accelerate EV adoption, from tax incentives and discounts on tolls and parking for EVs, to new fees on traditional internal combustion engines (ICE) and even banning ICE sales completely in some places.

Transitioning to a lower-carbon economy will require significant investment and creative policymaking. By building more walkable communities, replacing private vehicle trips with public transit, and using cleaner vehicle technologies, we will put the world on a path to avoid the worst impacts of climate change while delivering cleaner air and a more equitable and inclusive economy.

Joshua Goldman is the director of strategy and business development at Via where he works with cities and transit agencies around the world to develop innovative public mobility systems.