In November, Aspen Words announced the longlist for the fifth annual Aspen Words Literary Prize, a $35,000 award recognizing a work of fiction that addresses a vital social issue. The selected books explore questions of freedom and identity, exile and belonging, and are set against the ravages of colonialism, consumerism, and classism. While the jury works on selecting a shortlist, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, how they view their role as a writer in this cultural and political moment, and the best piece of writing advice they’ve received.

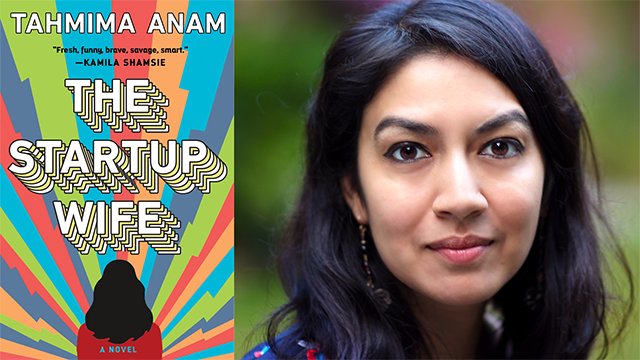

Tahmima Anam is an author and contributing opinion writer for The New York Times. In The Startup Wife, she takes on faith and the future with a gimlet eye and a deft touch. With a wickedly funny feminist look at startup culture and modern partnership, the book asks if technology—with all its limits and possibilities—can disrupt love.

How do you view your role as a writer in this cultural and political moment?

I’ve always believed that fiction is deeply political. There is no other artistic or cultural act that can so thoroughly allow us to see the world through another person’s eyes. Writers have an immense amount of power to move people, and I consider this a gift and privilege which I take very seriously. I grew up in a household of activists—my mother still regularly goes on marches! So it was never an option for me to write fiction simply for the pleasure of it. I think we are here to change peoples’ minds, to break their hearts, and to shift their perspectives as we give them small glimpses into what it’s like to be someone else living a totally different life on another corner of the planet. And at this moment in history, where all our fates are entwined under the shadow of the climate crisis, this mission feels all the more urgent.

What inspired you to write The Startup Wife?

Startups are all about revolution—the whole industry (or ecosystem, as it’s bizarrely referred to) promises to change every aspect of human interaction. And yet the workplace is still fundamentally biased against women. I wanted to tell a story about a woman, an immigrant woman, trying to make her way in this world, and finding that it’s not the haven she imagined it was. The story is also about power within relationships, in this case, in a marriage.

What is the core tenet of your book’s philosophy?

That in work, love, and all the places that matter, women are far from gaining equality.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve received on writing fiction?

Many years ago, when I was doing an MA in Creative writing, my teacher Andrew Motion, who was then the poet laureate of the UK, said “stop being so dutiful”—it was the moment I realized I was cleaving my story too closely to history, and not allowing my characters to go on their own journey. It’s important, even when telling a story that is based on real events, to remember that people read because they want to know what happens next. And so I’ve tried to hold those two interests—the political and moral objective, and the integrity of a story and its characters—in balance ever since.

What are you currently reading?

Khwabnama, by Aktaruzzaman Elias, translated by Arunava Sinha. It’s a magic-realist epic set in Bengal in the 1940s, and tells the story of a peasant rebellion called the Tebhaga movement. There is a vast cast of characters, a wayward spirit, and, in the background, the brutal realities of the Bengal famine. It’s an immersive reading experience.