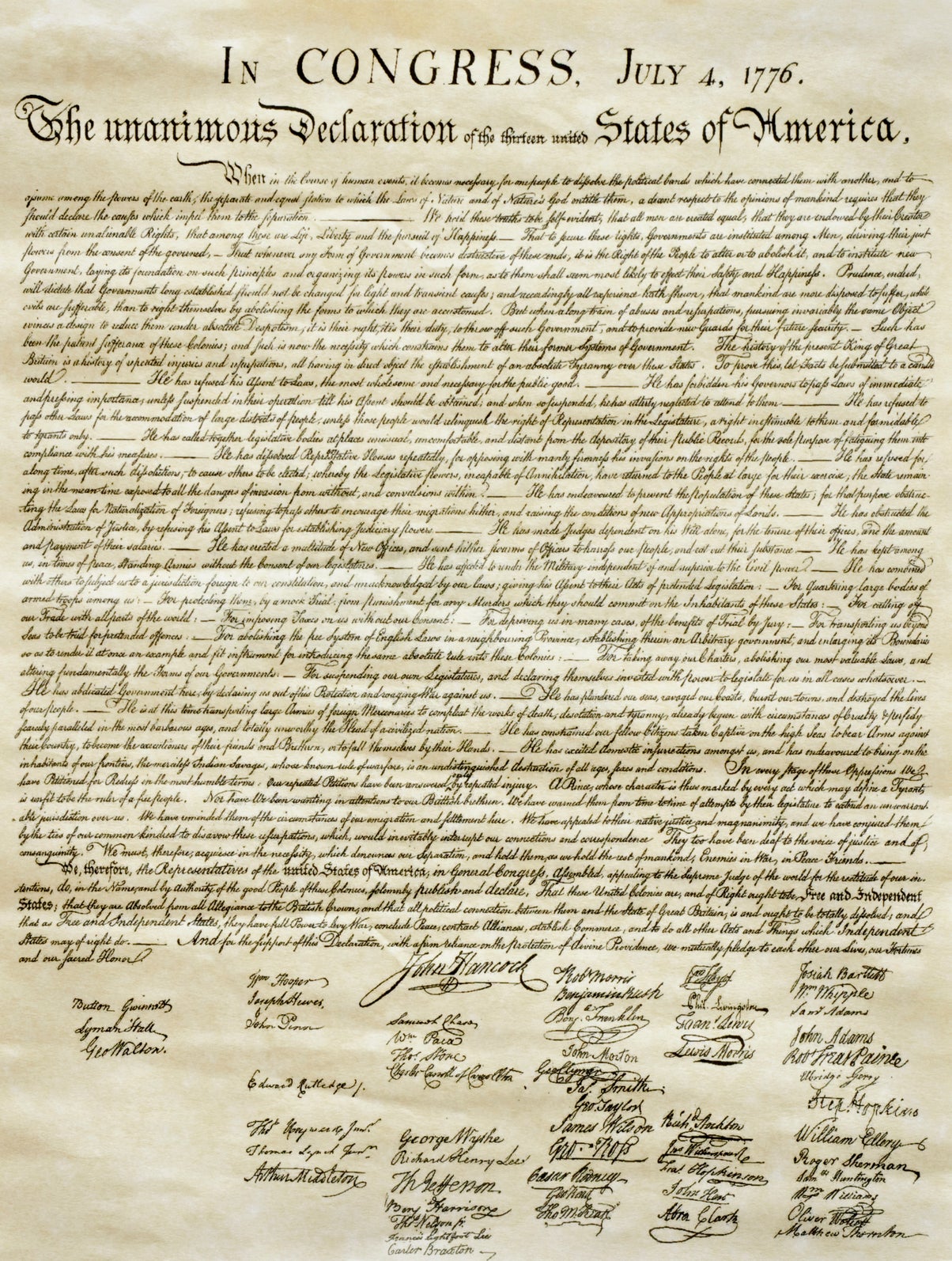

At the dawn of the American Revolution, a young member of Virginia’s elite planter class penned the sentence that has reverberated throughout history:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

For 240 years, the ideas Thomas Jefferson expressed in the Declaration of Independence have ignited imaginations, inspired song and verse, and aroused political campaigns, social movements, and revolutions around the world: “let freedom ring” … “God bless America” … “We shall overcome.”

But for America’s black population, freedom didn’t ring in 1776. It would take 87 years and a bloody civil war for most African Americans to gain their “unalienable Rights,” and another 100 years of courageous protests before those rights could be fully exercised. That duality played out across the country, and on Jefferson’s plantations.

Of the 607 men, women, and children Jefferson owned throughout his life, only 10 were freed on or before his death, at which time approximately 130 individuals had to be sold, along with Monticello, to account for his debts. Jefferson’s notion of liberty, while visionary for his time, did not extend to all people. Yet many enslaved individuals knew of his stirring words and were inspired by the Declaration’s proclamation of equality.

What should every American know about the paradox of the Declaration of Independence? The Aspen Institute Citizenship and American Identity Program’s “What Every American Should Know” initiative crowd sources ideas from a wide range of Americans into top 10 lists about what all Americans should know in order to be aware, effective, and engaged citizens. The goal of this project is to spark creative conversation about who we are as a nation today — and how we want to tell that story.

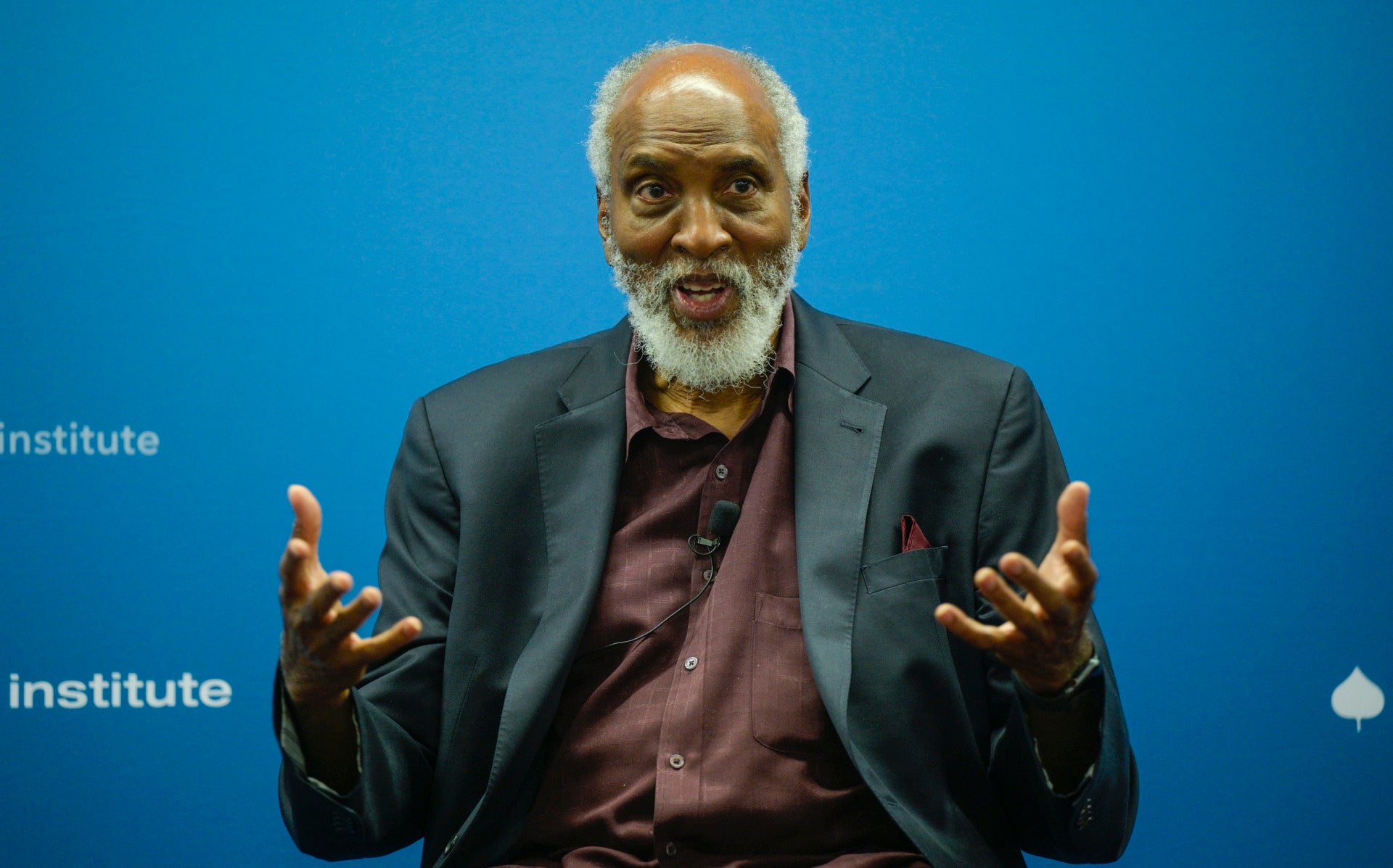

Below, Leslie Greene Bowman, president and CEO of theThomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello, shares what she together with foundation scholars and staff, thinks every American should know about the paradox of the Declaration of Independence — how it might have influenced Monticello’s enslaved families, future generations of African Americans, and freedom-seeking people around the world.

- The Fight for Freedom’s Promise

Jefferson’s words left an indelible imprint of freedom’s promise on Monticello’s enslaved families and their descendants, many of whom pursued equality and racial justice for their people.

Two examples: Peter Fossett was born a slave at Monticello, and settled in Ohio after his manumitted family purchased his freedom. As a free man, Fossett became a church pastor and an Underground Railroad conductor, bravely guiding his brethren to liberty.

William Monroe Trotter — a descendant of Elizabeth Hemings, enslaved at Monticello — founded the Boston Guardian newspaper, helped found the Niagara Movement, precursor to the NAACP, and vociferously challenged President Woodrow Wilson’s segregationist policies.

- Challenging Slavery

In early America, enslaved people struggled for their independence — in small but significant ways — every day.

In addition to the better-known slave revolts of the 18th and 19th centuries, slaves undertook daily actions to challenge their condition and assert autonomy — including work slowdowns, truancy, and feigned illness.

- The African Colonization Movement

Jefferson believed that blacks and whites could not co-exist in the American nation.

Along with political allies James Madison and James Monroe, Jefferson supported the American Colonization Society, a campaign advocating for African Americans to migrate to Africa. Many did, including members of Monticello’s enslaved community, settling in what became Liberia. In 1847, that fledgling nation incorporated ideas from America’s Declaration of Independence into its founding document.

- Jefferson’s Civil War Prediction

At the same time, Jefferson thought that the paradox of freedom in an age of slavery would ultimately destroy the new nation.

In “Notes on the State of Virginia,” Jefferson wrote, “I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep forever…” He believed that to keep slaves in bondage, with part of America in favor of abolition and part of America in favor of perpetuating slavery, would result in civil war. Jefferson’s prediction was correct: in 1861, the contest over slavery sparked a bloody civil war and the creation of two nations — Union and Confederacy — in the place of one.

- Frederick Douglass’ Independence Day Speech

In his 1850 Independence Day speech, Frederick Douglass, the great abolitionist and former slave, invoked the Declaration’s principles to excoriate America for the hypocrisy of its founding.

“What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than any other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is a constant victim.” Yet Douglass also found hope in those principles. “While drawing encouragement from the Declaration of Independence, the great principles it contains, and the genius of American Institutions,” he said “my spirit is also cheered by the obvious tendencies of the age.”

- Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I Have A Dream” Speech

In his famous “I have a dream” speech, delivered in 1963 from the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, Martin Luther King, Jr. also drew upon the Declaration’s promise to advance civil rights.

Borrowing from the Sage of Monticello, King shared his vision for America: “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up, live out the true meaning of its creed: We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.” Dr. King’s call was answered on July 2, 1964, when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act, outlawing racial discrimination in the United States.

- The Black Panther Party

In 1966, the Black Panther Party was founded in Oakland, California, to advocate for the constitutional rights of black Americans, rallying around a Ten-Point Program that referred back to Jefferson’s words.The program, a call-to-action for party members, closed with a modified version of the Declaration of Independence’s most famous paragraph: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal…it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security.”

- Women’s Rights and the Seneca Falls Convention

Another population who could not fully enjoy the liberties outlined in 1776 — women — drew upon the words of the Declaration of Independence to advance their social, civil, and religious rights at the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848.

Drafted by suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, the Declaration of Sentiments, following the structure of the original Declaration of Independence, was read and debated at the Seneca Falls Convention. The document called for equality with men before the law, in education, and employment. It was signed by 68 women and 32 men on July 20, 1848.

- The Global Impact of the Declaration of Independence

Beyond American borders, the ideas expressed in the Declaration of Independenc

e have been echoed in hundreds of like declarations around the globe.More than half of the countries represented at the United Nations have a founding document that can be called a declaration of independence — from Venezuela, Armenia, and the Republic of Ireland, to Yugoslavia, Korea, and even Haiti, the only nation borne out of a slave revolt.

- American Presidents Who Owned Slaves

Twelve American presidents were slaveholders. However, thanks to Jefferson’s copious record-keeping, we know more about plantation life at Monticello, and its enslaved community, than can be known about the vast majority of early American historical sites.

For more than 50 years, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation has been working to add a critical human dimension to the study of slavery through documentary research, ongoing archaeology, and a groundbreaking oral history project, Getting Word. Since 1993, the Foundation has conducted almost 200 interviews with descendants of Monticello’s enslaved families. For more information, please visit https://www.monticello.org/getting-word.

Ultimately, Jefferson’s most enduring legacy is not what he intended the Declaration of Independence to mean, but how succeeding generations have drawn inspiration from its words. History has proven that the prospect of equality and human freedom — life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness — belongs to all people, in all ages.

Leslie Greene Bowman is president and CEO of the Thomas Jefferson Foundation at Monticello, in Charlottesville, VA.