Photo by Kristina Sherk

Aspen Words will confer the inaugural $35,000 Aspen Words Literary Prize this year, recognizing a work of fiction with social impact. Twenty nominees are still in the running, and the diverse list includes 12 novels and eight short story collections covering a variety of critical issues and published by an array of presses. While the jury works on narrowing this list down to five finalists and a winner, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, the importance of fiction in understanding contemporary issues, and the books that have influenced them most.

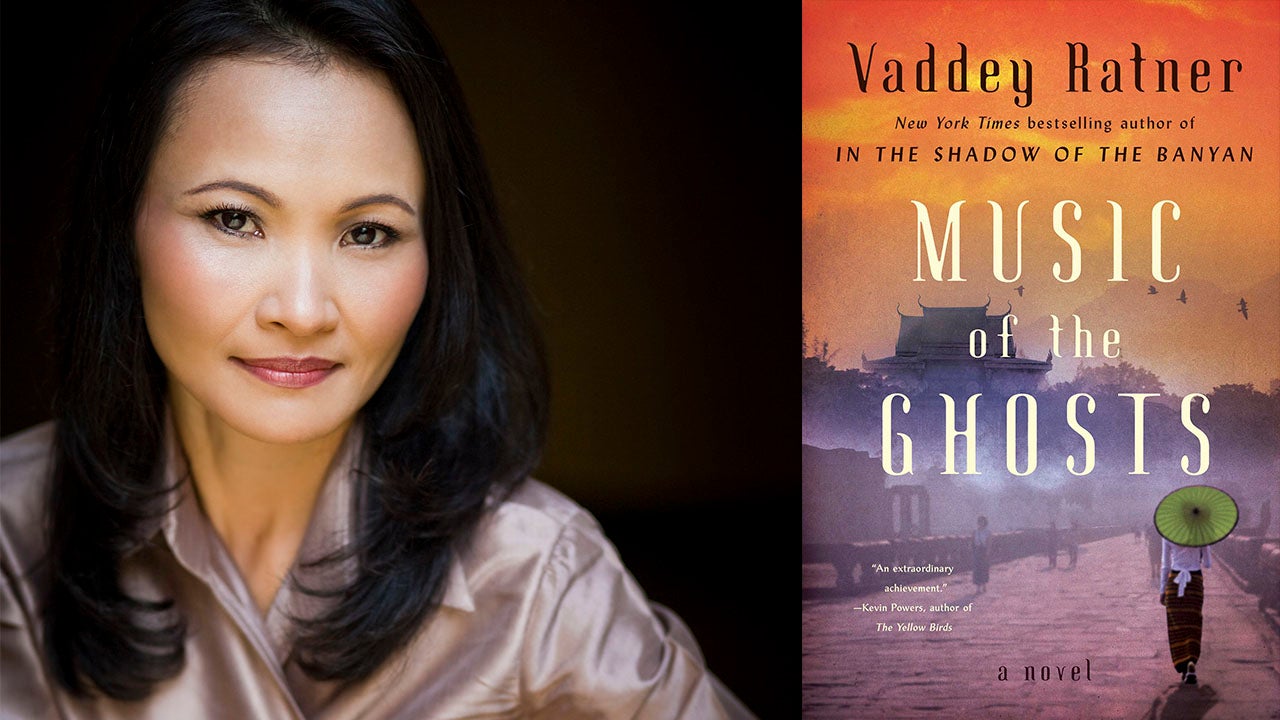

Vaddey Ratner’s Music of the Ghosts follows Teera, who escapes the Khmer Rouge regime in Cambodia as a child only to return decades later to meet a man who claims to have known her father in prison. The story is a personal one — Ratner herself survived the Khmer Rouge. Her debut novel, In the Shadow of the Banyan, was a New York Times bestseller and a finalist for both the 2013 PEN/Hemingway Award and the 2013 Indies Choice Book of the Year.

Why did you write Music of the Ghosts?

Essentially, I write to heal. Music of the Ghosts is not autobiographical, but it traverses an emotional landscape that is deeply personal. There is something of me in Teera, the young American woman returning to Cambodia, which she fled as a child refugee more than two decades before. And there is something of me in the Old Musician, the survivor who was left behind, scarred by the choices he was forced to make. Between them lies a journey that neither can complete alone, compelling each to probe the possibilities of atonement and forgiveness.

My first novel, In the Shadow of the Banyan, is a story of survival. Music of the Ghosts is a story of survivors, both victims and perpetrators of atrocity. It asks, How can we move on when some may have committed such unforgivable wrongs? How can we live together?

What was the most challenging thing about writing this book?

Beyond the emotional trauma of reliving my own childhood ordeals was the challenge of trying to imagine the suffering that went beyond my own experience. I had to place myself in the mind and heart of a soldier, enduring the trials of a jungle training camp. I slipped in and out of torture chambers, weaving my words through the haunted corridors, trying to elicit light from the dark, reaching for hope. The writing seared my soul, but I emerged grateful.

My constant aim is not simply to portray suffering or injustice but to show the courage of those who, against the greatest odds, maintain their dignity and their humanity towards others. Ultimately, this is a story not only about healing but also about the rediscovery of home, and the possibility of love. Music is so important in the novel because of its redemptive quality, its ability to transport a listener, to evoke emotion in ways that words cannot. I tried to reflect that power in the writing, and in the very structure of the novel.

How might fiction help us to explore contemporary issues?

More than 35 years ago, I arrived in the US as a child refugee of war. From a huge extended family, only my mother and I escaped together, eventually resettling to Missouri. Today the world’s attention is focused on refugees fleeing Syria, Afghanistan, northern Africa, and now Myanmar. This mass movement of people elicits a wide range of response — compassion and kindness but also fear and hatred.

I’ve seen where the rhetoric of fear and hatred can lead. I know in my bones that, under certain conditions, we all have the potential to inflict violence, to perpetuate it. So, how we react in the wake of chaos, in the wake of profound suffering, is so important, not just for the victims and survivors of violence, but ultimately for all of us, for our human society as a whole.

The world is more connected. Whether we travel, or stay in one place, we come into contact daily with people of different backgrounds, experiences, and beliefs. How do we make sense of our own lives amidst these clashes of identity? How do we learn to understand one another, to make sense of injustice, without being overwhelmed by hatred or by grief?

An essential role of fiction is that it enables us to find reflections of ourselves in lives that are so vastly different from our own. I’m certainly nourished this way as a reader of fiction. The best writing leaves me transformed, more hopeful — not because it glosses over the things that divide us, but because it illuminates both our differences and our commonalities with compassion.