Mass evictions are a looming threat to 19-23 million American renters

Across the country, renters and tenants advocates are sounding the alarm about the coming eviction crisis, referring to it as an avalanche or tsunami. Over the past five months, more than 44 million Americans have filed for unemployment amid the COVID-19 pandemic. As the recession continues, economic stimulus payments are spent, and expanded Unemployment Insurance expires, many of these displaced workers will be unable to make housing payments.

Mass evictions would be a disaster. For both individuals and families, evictions result in severe harm; when they become widespread, there are also significant consequences for entire communities and even the speed of economic recovery. Policymakers are actively seeking solutions, but it is difficult to prepare without knowing the size of the problem.

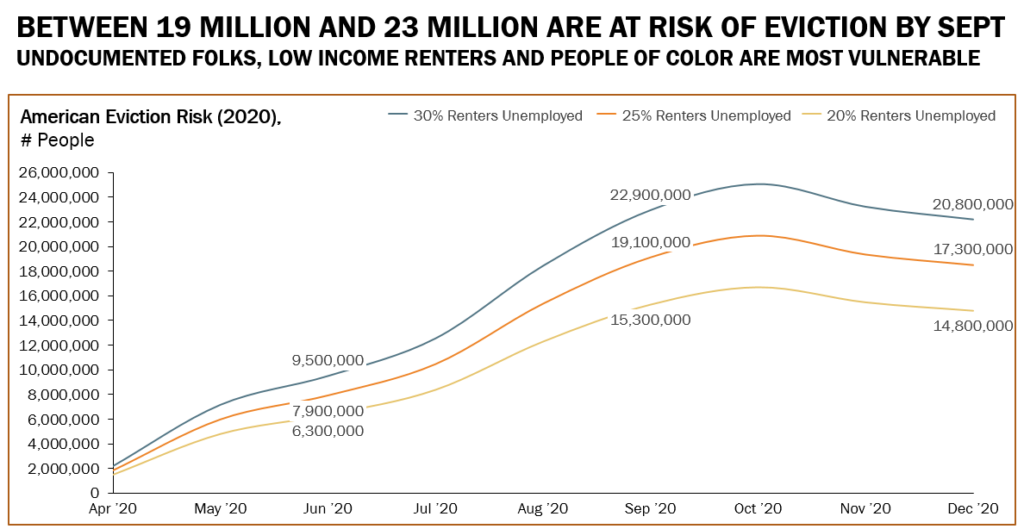

The COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project (CEDP) was formed to solve that problem. It is a coalition of economic researchers and legal experts who developed a model to estimate eviction risk nationally and at the state level. The disturbing result: 19 to 23 million, or one in five of the 110 million Americans who live in renter households, are at risk of eviction by September 30, 2020.

CEDP co-founder Sam Gilman reached the estimate by building a model that incorporated data on renter households’ income, savings, and housing cost burdens (a household is cost-burdened if they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs such as rent or mortgage, utilities, insurance, taxes, and maintenance). The model also accounted for new income through stimulus payments, enhanced unemployment insurance, and state unemployment insurance in each of the 50 states and Washington, DC. This allowed the organization to predict how many renters are at risk depending on the level of unemployment renters are experiencing. If their unemployment rate is 25 percent, 19 million people would be at risk of eviction by September 30, as their unemployment benefits expire, stimulus payments are spent, and savings dwindle; that rises to 23 million if renters’ unemployment rate is 30 percent.

The costs of eviction

In January 2020, Aspen’s Financial Security Program (FSP) published Strong Foundations, reporting findings from our current research initiative on housing affordability and stability. We and others have documented high levels of financial insecurity among renters over the past two decades. Even before the pandemic, renter households had lower incomes (median of $40,500 in 2018, compared to the national median of $63,000), more consumer debt relative to their income, fewer assets, and low liquid savings. More than 40 percent of renters were cost-burdened before this unemployment crisis; one in four was spending more than half their income on housing. This level of insecurity has been building for decades; median monthly rents have grown more than renters’ incomes in every year since 2001.

FSP also found that the number of households experiencing instability—including being threatened with eviction, having initial eviction paperwork filed in court, actually being evicted, and becoming homeless—was relatively small, between 3-6 million per year, but that these individuals and families experienced severe, long-lasting harm to their financial security, health, education, and well-being. Many landlords will not rent to anyone with a past eviction or debt owed to a previous landlord so displaced families often have few options except substandard homes in disinvested neighborhoods that offer little access to good jobs or transit. Court costs and moving expenses tend to consume all the household’s savings and assets, leaving them more vulnerable to future income or expense shocks which most households experience at least once a year. Children fall behind at school and some students drop out altogether—which jeopardizes their ability to earn a living when they are adults.

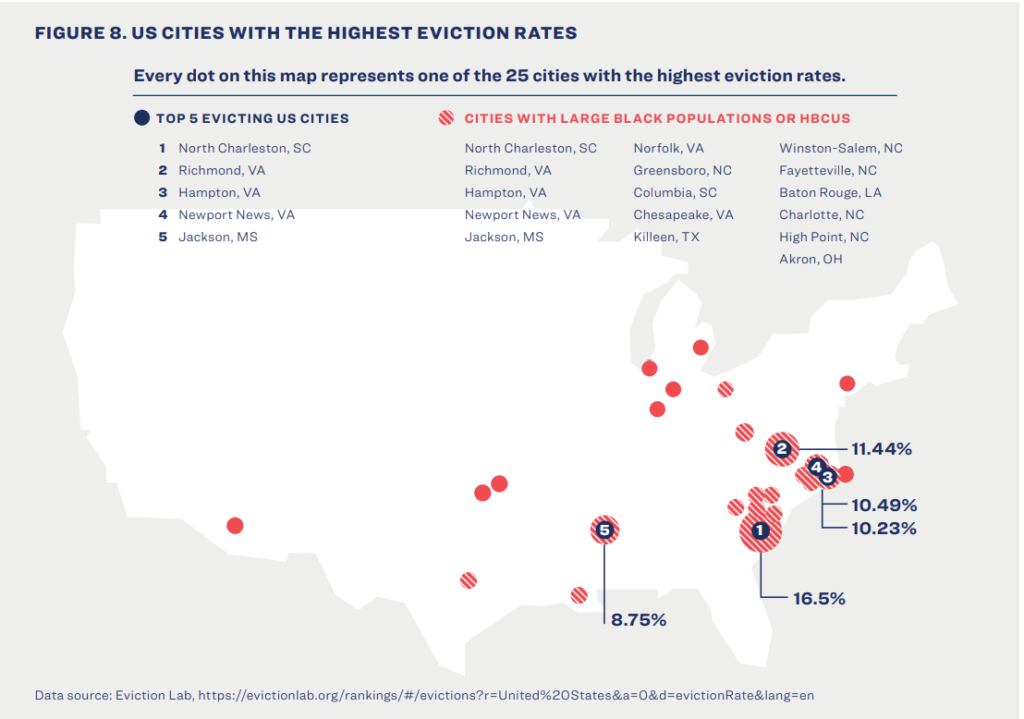

The pain of eviction is not evenly distributed. Data indicate that both geography and discrimination play significant roles. Tenants’ rights and eviction laws vary widely. Some areas of the country are eviction hotspots. Of the 25 large US cities with the highest eviction rates, six are located in Virginia and five in North Carolina. Racial discrimination is evident, as Black and Latinx people, particularly mothers and their kids, are the most likely to experience eviction. Other groups who suffer from high rates of eviction include people who are disabled, were formerly incarcerated, are undocumented, and/or are LGBTQ.

Notably, these same groups have been hard-hit by COVID-19 and have higher-than-average unemployment rates. An eviction avalanche would have disastrous results, not only for millions of families but also for hard-hit regions and the pace of economic recovery.

Policymakers at every level of government must act now

There is still time to prevent disaster. The most effective way to keep renters in their homes is to pay their rent or provide ongoing cash transfers. Past research on emergency rental assistance and guaranteed income experiments have been proven to help people avoid delinquency on costs like utilities and can reduce evictions.

Ideally, the federal government would fund renter assistance. The US House of Representatives’ HEROES Act, passed in May, would authorize a $100 billion fund, but the Senate is unlikely to agree to that amount. It might also not be enough. The National Low Income Housing Coalition calls $100 billion the minimum viable amount; the National Apartment Association and National Multifamily Housing Council, which each represent landlords and property managers, estimate that renters may need $144 billion in assistance.

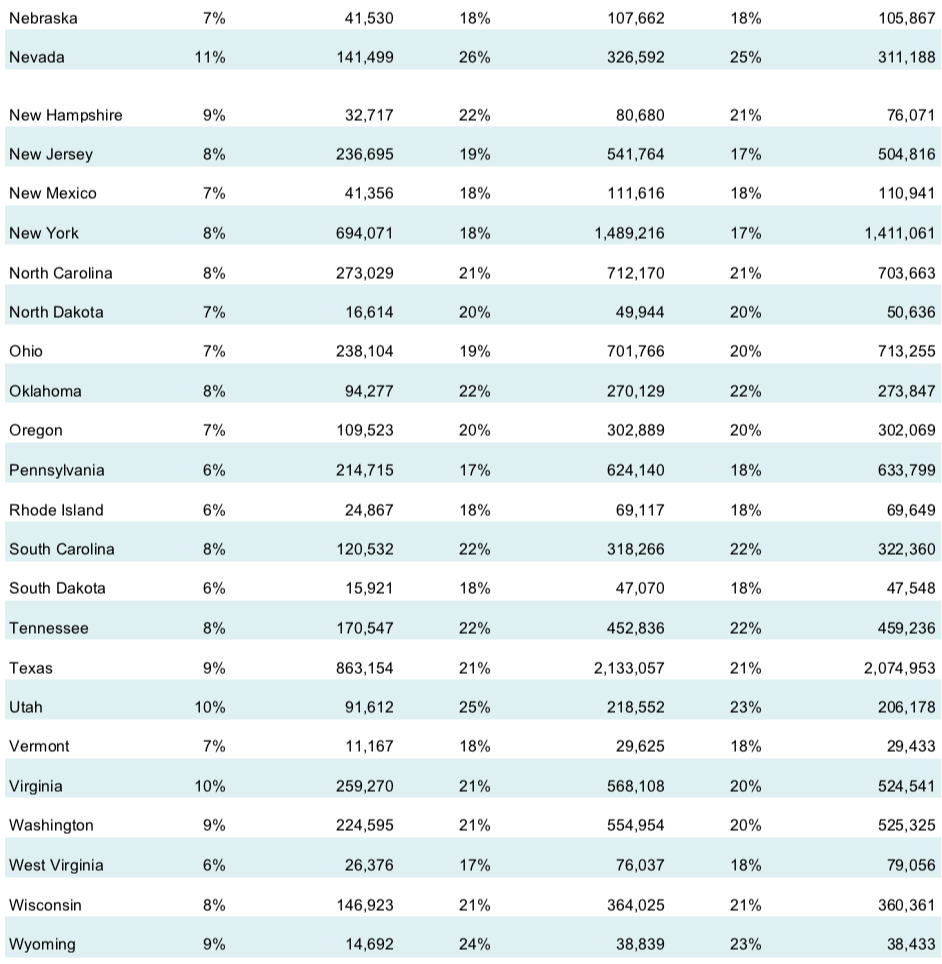

To help state and local policymakers understand the challenges they face, the COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project also provides state-level estimates of how many of their renters are at risk of eviction under different unemployment scenarios.

There are already promising interventions happening across the country. Many states, counties, and cities have already established short-term emergency rental assistance programs, ranging from one-time infusions of a few hundred dollars to fully covering two months of rent. Foundations and nonprofits have also created emergency funds for renters. They could be important partners in a time of falling government revenues and rising expenses.

State and local policymakers can also extend eviction moratoria, specify economic criteria (such as a state unemployment rate below a certain percent) that must be met before they expire, enhance tenant protections for the duration of the recession, and require landlords to accept repayment of past-due rent over at least 6 months.

Our groups will continue working on this issue together. A full brief on the CEPD eviction risk model will be published soon, and the FSP team will share findings from our expert survey on their highest priority strategies to increase access to stable, accessible housing they can afford.

Sign up for updates from the Aspen Financial Security Program to be the first to know when our findings are available.