Meryl Justin Chertoff is Director of The Aspen Institute’s Justice and Society Program.

Surprised that the Affordable Care Act was upheld through a complex ruling that created an unusual alliance of Supreme Court justices? Wonder why the Defense of Marriage Act case is considered by many to be the more likely of the two same sex-marriage cases now before the Court to be decided in favor of advocates of same-sex marriage?

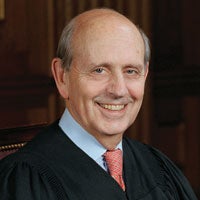

Both involve the complex relationship of states’ rights to the US Constitution, and both indicate why one of the hottest areas of constitutional thought today relates to the “dual sovereignty” called federalism, which will be among the topics discussed at this year’s Susman Conversation on the Constitution and the Courts, July 3rd in Aspen. Featured guests include Supreme Court Associate Justice Stephen Breyer and Chief Justice of the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts Margaret Marshall.

In 1977, Supreme Court Associate Justice William Brennan published an article in the Harvard Law Review that has long resonated with constitutional scholars, particularly those interested in federalism. Frustrated by what he saw as a conservative turn by the Burger Court away from the expansion of civil rights and liberties that had characterized the Warren Court, Justice Brennan turned back to his roots on the New Jersey Supreme Court. On the occasion of his 70th birthday, he urged advocates to look beyond the federal courts and the US Constitution, and to seek a potentially more sympathetic venue by appealing to state constitutions and pursuing redress through state courts.

Setting aside the intellectual force of Justice Brennan’s arguments, it would not be unfair to guess at some of his motives. As former Indiana Chief Justice Randall Shepard noted in a 1996 article, by the mid-1970s, Justice Brennan began to find himself “at the losing end of cases.” While in the 1960s Justice Brennan wrote just 33 dissenting opinions and cast only 67 dissenting votes, in the 1970s he wrote 198 dissenting opinions and cast 452 dissenting votes. In Shepard’s view, Brennan “concluded that the revolution was over as far as the Supreme Court was concerned,” and “quite candidly announced that the war should be waged on another front.”

Brennan’s version of federalism arguably speaks to advocates today. As some observers have concluded, the Roberts Court, like the Burger Court, is uninterested in expanding rights for discrete and insular minorities or criminal defendants. And so those advocates are examining anew the opportunity to take their battles to the state courts.

This year’s Susman Conversation speakers have ample experience in these matters. Justice Breyer, viewed by many as having assumed Justice Brennan’s role as the liberal conscience of the Court, was a professor at Harvard Law School when its Law Review published Brennan’s landmark article. Like the late justice, the sitting justice is imbued with a pragmatic approach to constitutional jurisprudence.

Joining Justice Breyer is Justice Marshall, who authored the opinion in “Goodridge v. Department of Public Health,” which found a right to same-sex marriage in the Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. (As Bay Staters are quick to note, the Massachusetts Constitution is the oldest written constitution in the world, authored by John Adams and enacted in 1776, giving it the jump by seven years on its US sibling.)

With two erudite jurists, the discussion at this year’s Susman Conversation promises to be an intellectual feast, much like last year’s conversation with Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy on civics and challenges of the Supreme Court:

We hope that you will join us on July 3 in the Greenwald Pavilion on the Aspen Meadows campus. Tickets for the event go on sale June 19th at www.aspenshowtix.com.