Inspiration for a story can strike at any point. Sometimes it is borne out of a new experience, other times it comes from re-examining your daily life. The authors nominated for the Aspen Words Literary Prize tackled many subjects that have made their way into today’s news cycle—immigration, police brutality, gun violence, and LGBTQ issues. While we can learn about these through traditional sources of information, Aspen Words Executive Director Adrienne Brodeur believes that “fiction allows us to examine these issues with more compassion.” Seven nominees shared their sources of inspiration with us.

Tayari Jones, author of An American Marriage

I can’t really say when I first became aware of the ways that the justice system terrorizes the African American community. I don’t know anyone who hasn’t been touched in some way by the system— relatives, friends, colleagues. Prison and jail are woven into the fabric of our culture. Sometimes awareness of a problem can hit you like a lightning bolt, but with this issue, there was no lightning bolt. It has been raining all my life.

Brandon Hobson, author of Where the Dead Sit Talking

I know a lot about the foster care system in Oklahoma from personal experience. Native Americans are sometimes placed with families outside their tribe through contracts made with the state’s Department of Human Services. Lots of Native American teenagers (teenagers of all races, actually) get shuffled from home to home, shelter to shelter, through the foster care system for months and even years. It’s very sad, and I’ve seen little fiction exploring these issues. In addition, the justice system is detrimental in that people are put in jail and prison for nonviolent crimes such as drug possession, as is the case with my protagonist’s mother, when actually they should be considered for treatment facilities instead. All this was an inherent inspiration for my novel.

Elaine Castillo, author of America is Not the Heart

I knew I wanted to write about a young queer woman who was living in exile as a former member of the New People’s Army, the armed wing of the Communist Party of the Philippines. It was important for me to push back against the idea of what a political novel is meant to look like, who it’s meant to focus on: that “serious” political novels are about war, empire, history (and, usually, men). There’s no lack of war, empire or history in the book. But it was equally important to write about my protagonist Hero not just as a former political operative, but as a queer Filipina.

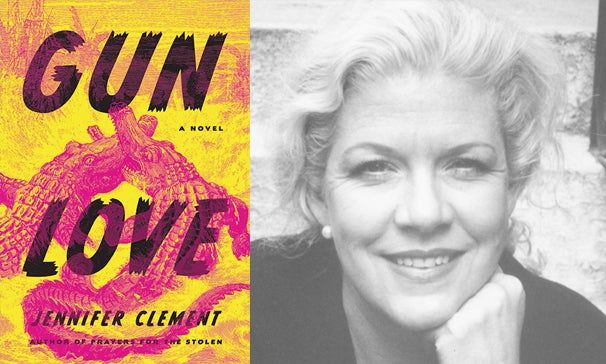

Jennifer Clement, author of Gun Love

The inspiration for my novel comes from my concern regarding gun violence in the US, the effect of 20,000 guns crossing a day into Mexico, which fuels and sustains Mexico’s crime, and the effect of guns on the almost complete destruction of the native peoples. My novel stands on over eleven years of research on all these subjects. I’ve written journalistic pieces on the NRA and I’ve interviewed survivors of mass shootings. I am also interested in telling stories of how violence affects women and girls.

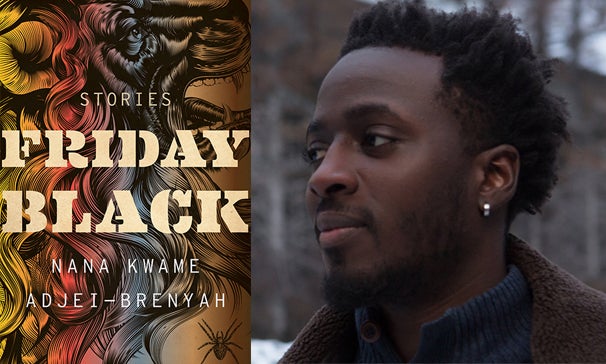

Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah, author of Friday Black

I’m inspired all the time by people not giving up. I’m inspired by all the people who work to make sure that when Black people are murdered with impunity the names of the killed are never forgotten. Those people that challenge the machine. I’m inspired by the love that persists despite all the craziness.

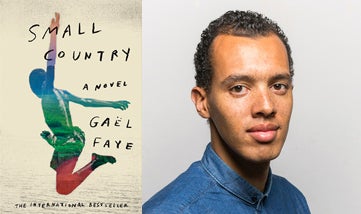

Gaël Faye, author of Small Country

I wrote this novel to awaken the memory of a forgotten world—with its perfumes, colors and smells—to cry out to the world that we did exist, with our simple lives, the daily grind, our boredom. I aimed to shout-out to the universe that we knew what happiness was, before being sent to the four corners of the world to become a group of exiles, refugees, immigrants, migrants. I have written in order to tell about tragedies, but also days of light that preceded them.

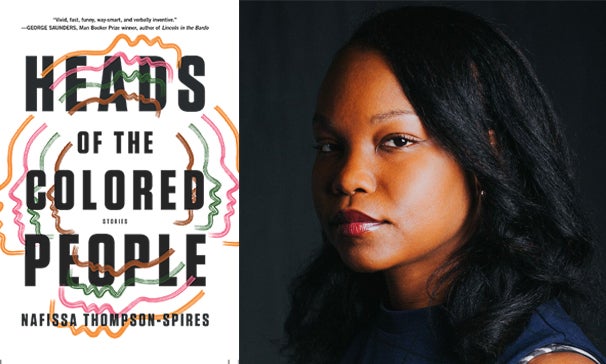

Nafissa Thompson-Spires, author of Heads of the Colored People

The original The Heads of the Colored People: Done with a Whitewash Brush, written by abolitionist doctor and poet James McCune Smith, inspired my title and many of my concerns in the collection. I also really wanted to tell black stories I hadn’t read before—stories of black nerds, black people who were isolated among white people, black middle-class characters struggling with racism and a host of banal issues.