The economy is growing, the stock market is rising, and job growth is fairly consistent, month after month. Employment is recovering. And yet, America’s labor market participation rates have continued to slump since the Great Recession.

There’s consistent talk about worker shortages. Employers are reporting difficulty hiring qualified workers, and some regional markets have high numbers of job openings unfilled. The fears of a tightening labor market and rising inflation led Federal Reserve Chair Janet Yellen to say in November 2017 that interest rates would continue to slowly rise.

Let’s consider taking the alarm level over worker shortages down some decibels. There is a net growth in total employment. There are also plenty of job openings. Yet there should be at least 5.8 million more people at work. With millions of workers disengaged from jobs, can this be a real “worker shortage?” Maybe we should respond to the lowered participation rate by addressing lagging wages and salaries and repairing the fraying social contract to attract those millions back into the labor force.

Consider this:

There can’t be a labor shortage when 5.8 million workers are missing in action.

That’s the alarming fact hidden in plain sight within the good news of job growth. The 20 million increase in jobs between 2010 and 2017 was a huge relief. But during the same time, the labor market participation rate continued to slide. The percentage of the labor force that is employed fell a full two percentage points in the same period (from 64.8 percent to 62.7 percent). Between 1993 and 2006 (excluding recessions), the labor force participation rate averaged 66.6 percent. A strong economy should pull individuals “off the bench” and back to paid work. If today’s economy were revving at the higher participation rate of 2010, 5.8 million more individuals would be found on the payrolls.

Another 4.8 million are working (and therefore counted as being within the labor force), but are part-time employees for economic reasons when they’d prefer full-time posts. Combined, this 10.8 million is the reserve pool of workers that might be engaged.

Wages and salaries are lagging.

Where is the evidence you’d expect to see of overheating demand for workers? If workers are indeed in short supply and businesses are competing to hire, then why are wages and salaries not doing far better? As the chart from the Federal Reserve below documents, median wages not only took a huge downward hit in the Great Recession, they are, even these many years later, far from reaching the trend lines for the past few decades.

The shift to service economy jobs or loss of manufacturing does not account for this trend as the track for college educated and full-time workers differs only slightly from the median wage trend for service workers. And for much of the past four decades, wage growth has lagged behind productivity gains as well.

Employers can shoulder higher pay and continue to see very high profits.

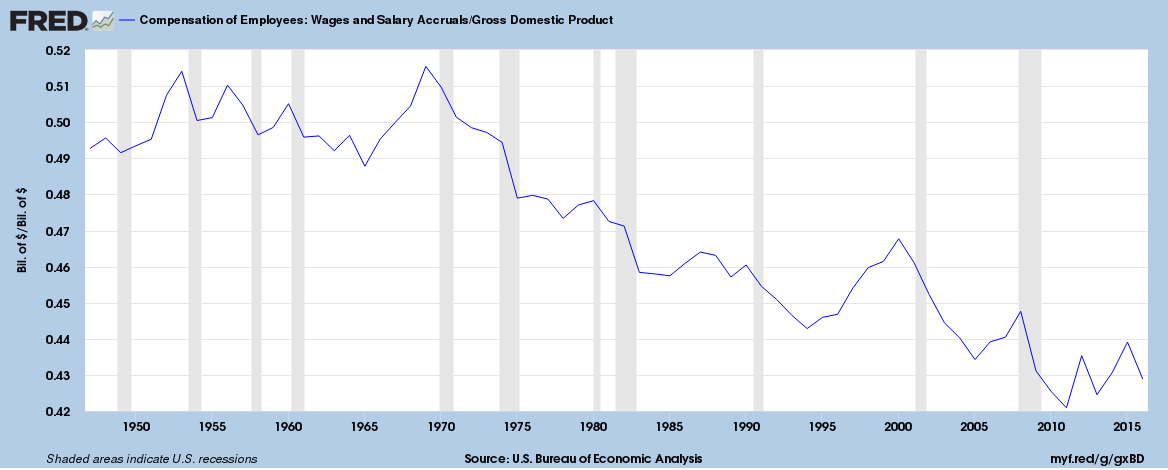

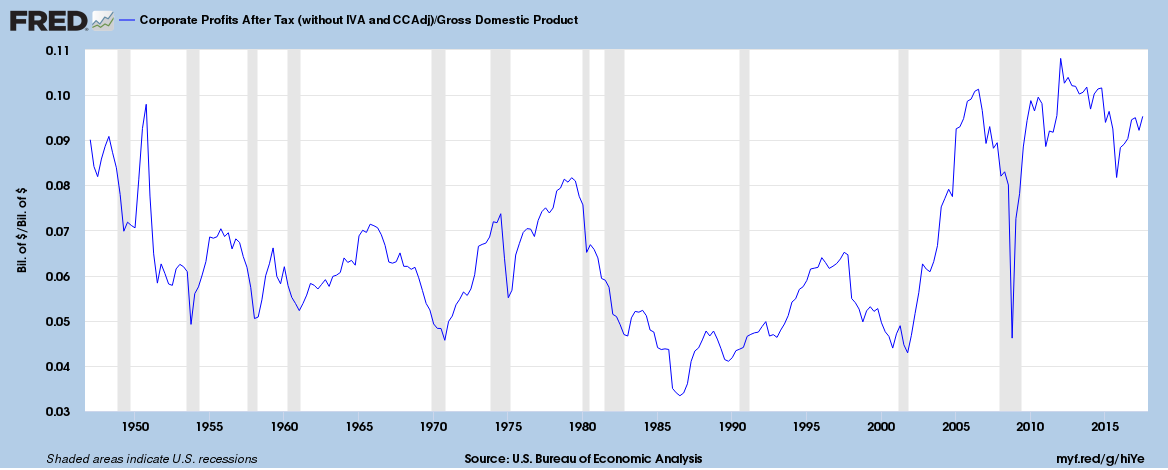

Business profits soared since the 1980s and from the Great Recession to today. Profits after taxes as a share of GDP came close to doubling in the few years between 2008 and 2016. At the same time, wage and salary compensation decreased as a share of GDP. The table below shows the rebalancing away from pay to workers and into business profits. Corporate profits after taxes rose from $450 billion in 2000, exceeded $700 billion in 2008, and last year cleared $1.7 trillion. That’s a great run of fortune – a swing of four percentage points of GDP toward corporate profits. If the four percentage point margin currently going to profits were evenly split between profits and wages, it would be sufficient to offer a $2,500 pay boost to an average worker. Yet, even with that split, corporate profits after taxes would remain at the highest level since the heydays of the early post-WWII era.

| 1970s | 2000 | 2008 | 2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wages/GDP | 50% | 47% | 44.8% | 42.9% |

| Corporate Profit After Taxes/GDP | 2-3.5% | 4.3% $450 B |

4.8% $704 B |

9.0% $1,701 B |

For four decades, almost without interruption, people who work for pay have lost ground, and standards of living have declined. A recent international study of income and wealth distribution emphasized the rapidly growing inequality in the United States, contrasting trends in Europe and many other parts of the world. Continuing this course has real risks of political, social, and economic stress and potential catastrophes.

Instead of slowing down the economy, businesses, workers, policymakers, and their partners in the nonprofit sector should find ways to attract millions more back into the work world. That would likely also help dampen yawning income inequality and set the stage for a more inclusive economy with broadly shared prosperity. To set the American economy on a course for truly stable and broadly shared growth, we must find and engage the 5.8 million missing workers – for their gain and for our own.

Share now

Tweet “Instead of slowing down the economy, businesses, workers, policymakers, and their partners in the nonprofit sector should find ways to attract millions more back into the work world.” @mpopov1229

Tweet “To set the American economy on a course for truly stable and broadly shared growth, we must find and engage the 5.8 million missing workers – for their gain and for our own.” @mpopov1229

Tweet “For four decades, almost without interruption, people who work for pay have lost ground… Continuing this course has real risks of political, social, and economic stress.” @mpopov1229

Keep in touch

Good Companies/Good Jobs encourages and equips business leaders to enact strategies that simultaneously produce outstanding outcomes for their businesses and their frontline workers. Good Companies/Good Jobs is an initiative of the Economic Opportunities Program. Learn how the Economic Opportunities Program is helping low- and moderate-income Americans connect to and thrive in a changing economy. Follow us on social media and join our mailing list to stay up-to-date on publications, blog posts, and other announcements.