Photo by Jillian Edelstein

Aspen Words will confer the inaugural $35,000 Aspen Words Literary Prize this year, recognizing a work of fiction with social impact. Twenty nominees are still in the running, and the diverse list includes 12 novels and eight short story collections covering a variety of critical issues and published by an array of presses. While the jury works on narrowing this list down to five finalists and a winner, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, the importance of fiction in understanding contemporary issues, and the books that have influenced them most.

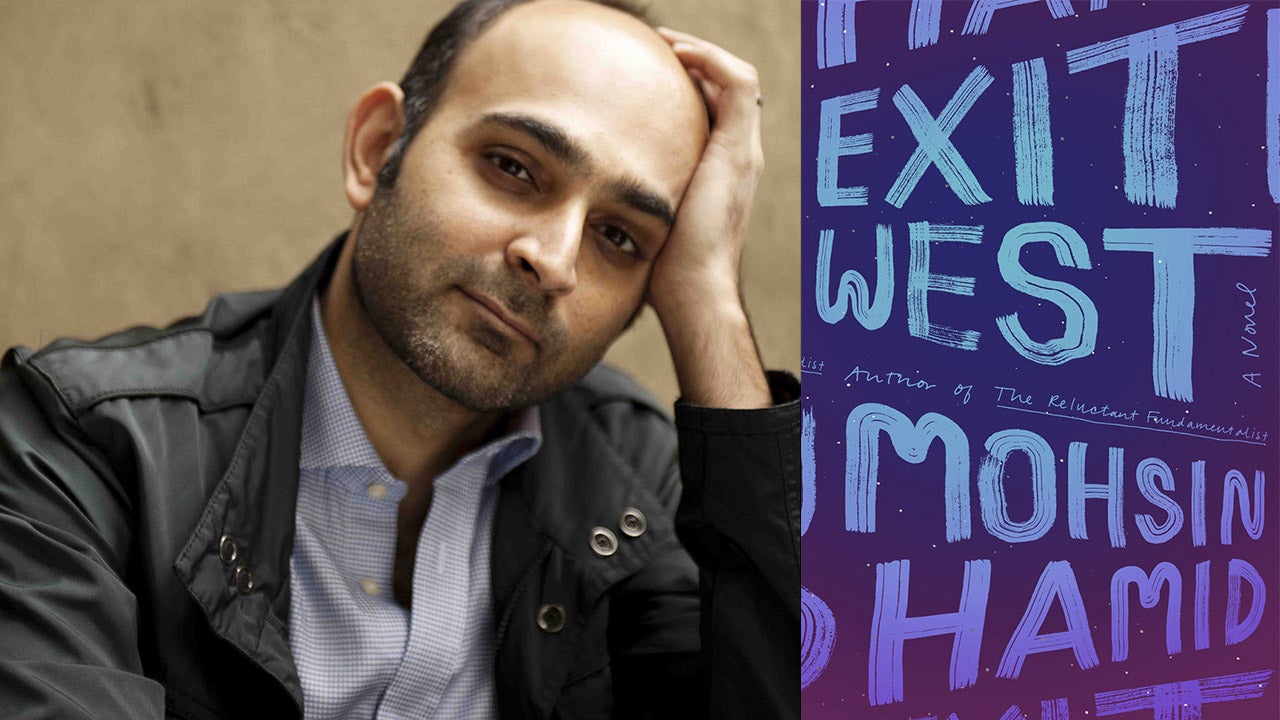

Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West tells the story of a young couple who flee an unnamed war-torn country to face discrimination, hardship, and unfamiliar territory as they move around the world in search of a home. Hamid, who has his own globetrotting background, has published three other novels (Moth Smoke, The Reluctant Fundamentalist, How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia) and a book of essays, Discontent and Its Civilizations.

Why did you write Exit West?

I am a mongrel, a hybrid. I migrated from Pakistan to California at the age of 3, back to Pakistan at 9, to America again at 18, London at 30, and then Pakistan once more at 38. I take the current backlash against migrants very personally. The book is my attempt to write against this growing anti-migrant sentiment. I wanted to portray migrants as heroes, not criminals. But more than that, I wanted to show that everyone is a migrant, even those who never move geographically, because moving through time, aging, is itself a form of migration. Instead of inevitable conflict, I wanted to find a space of recognition, of mutual and shared sorrow, between the person who has moved to a foreign country and the person who has begun to feel foreign in the country of their own birth. And I wanted to suggest a future of radical migration that expressed elements of optimism, because if we can’t look to the future with optimism we are prone to exploitation by political nostalgia, leaders who promise to make the future like the past.

How might fiction help us to explore contemporary issues?

Fiction allows us to imagine being other people. Not merely to see them from the outside, but to imagine them as if we were them. It makes possible a blurring of boundaries. Between reader and character. And also between reader and writer. When you read a book, you are alone but you contain the thoughts of two people inside of you: your own thoughts, and the thoughts of the writer. Who are you in that moment? Yourself or someone else? Your sense of self begins to blur. A strange fertility becomes possible. And in that moment, as borders in the mind start to shift, new thinking becomes possible, and new politics too.

What book(s) have made you see the world differently? How?

So many. My life has been shaped by books, ever since I was a child. Charlotte’s Web by E. B. White, for example, made me begin to consider that death is inevitable and deeply sad — but that it is also natural, and need not necessarily be terrifying. Chinua Achebe’s No Longer At Ease, which I read in secondary school, made me realize that my experience as someone who had moved to the West and then returned to Pakistan was part of a much larger, global, post-colonial process. I understood from Achebe that the world was full of people like me, baffled like me. When I read Toni Morrison’s Beloved it was the first time that I began to understand how horrifying slavery in the United States truly was, and how ferociously its echoes persisted across generations. It has affected my politics and thinking ever since.