Aspen Words will confer the inaugural $35,000 Aspen Words Literary Prize this year, recognizing a work of fiction with social impact. Twenty nominees are still in the running, and the diverse list includes 12 novels and eight short story collections covering a variety of critical issues and published by an array of presses. While the jury works on narrowing this list down to five finalists and a winner, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, the importance of fiction in understanding contemporary issues, and the books that have influenced them most.

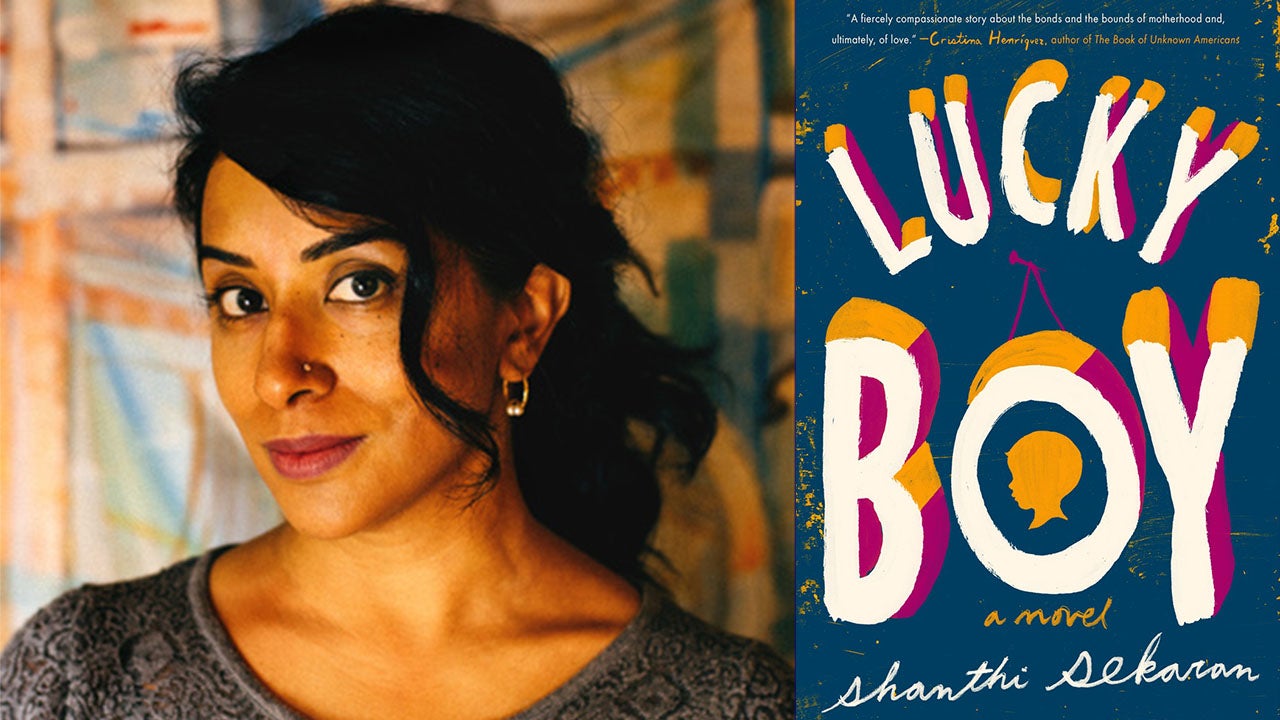

Shanthi Sekaran’s novel Lucky Boy follows two main protagonists — Soli, a pregnant 18-year-old who journeys across the Mexican border into the US, and Kavya, a Californian daughter of Indian immigrants intending to adopt a child — as their lives intersect in difficult and poignant ways. This is Sekaran’s second novel. Her first, The Prayer Room, was released in 2008.

Why did you write Lucky Boy?

I think Lucky Boy was brewing inside of me my entire life. I grew up the child of immigrants; my parents were doctors in Sacramento, California. I knew well my family’s immigration story and I could see, from a distance, the stories of immigrants from other countries. From a very young age, I could see the disparities between what my parents had and what other immigrants had, in a material sense. I could see that the “American experience” could turn out very differently for different categories of immigrants, in terms of opportunities afforded, assimilation experiences, and community cohesion.

Lucky Boy grew out of this awareness. I wanted to tell an immigration story that was truer and more complex than any I’d previously seen. I wanted to step past the brown/white racial binary and explore the dynamics of privilege between two brown families. When I learned about what was happening to undocumented families, I knew I wanted to understand that story.

I started writing Lucky Boy as a book about two mothers who wanted the same child, but it grew into an examination of the American landscape, how this country treats different types of immigrants differently, how access and privilege and an unspoken caste system influence this thing we call the American dream.

What was the most challenging thing about writing this book?

I faced my greatest challenges in the first year of writing. It took a lot of character exploration and research before I felt equipped to tell the story of Soli, who’s Mexican, undocumented, and completely new to the United States. For a long time, writing her character was an act of blind faith. I had to trust that building her slowly, layering her personality and experience, would eventually result in a whole and vibrant character. But for a long time, I felt like a fraud. I knew there was some essential part of her that I was not understanding. I realized, eventually, that I was going to have to get myself to Mexico. I was going to have to personally see and feel the place that Soli called home. Out of pure serendipity, I met someone who offered to host me at their artists’ residency in a little town outside of Oaxaca. Six months later, I was there. The experience was invaluable. It helped me flesh out the physical details of Soli’s native world and it strengthened my storytelling on a much deeper level. Of course, I will never fully know what it means to come from Mexico, to be a Mexican immigrant. But setting foot in Oaxaca, breathing its air, I knew that in order to understand Soli’s life in America I would have to understand what she’d left behind.

How might fiction help us to explore contemporary issues?

Contemporary issues wouldn’t exist without the stories behind them. Every statistic can be traced back to a personal drama. Contemporary issues are really just stories, stripped of their individual characters and repackaged as news segments.

Fiction has the power to re-charge an issue with breath and blood. It reminds us of why we care — or should care — about a particular issue. And really, it’s only when we personally relate to a problem that we begin to want to solve it. Unlike nonfiction, fiction can dive into the deepest depths of a character’s consciousness, until we, as readers, struggle to separate a character’s soul from our own.

What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

I learned early on that words could hurt. I was in kindergarten, riding the bus to school, and decided to sit in the back. I had much older siblings and didn’t know the unwritten social rules that banned little kids from big kid territory. So I sat in the back. That’s where I experienced my first assault by language — a big kid, a seventh grader, telling me that my skin was gross, that I’d been born in a toilet. It took just one person and a handful of words to make me feel ugly. It took the silence of the kids around him to tell me he was right.

Later that day, I saw what else words could do. A friend of mine saw that I was upset at the end of the afternoon — I’m guessing I was dreading the bus ride home — and brought me over to our kindergarten teacher. I didn’t tell Mrs. Waltermeyer what the seventh-grader had said — the words themselves were too much to utter. I told her that my brown skin was ugly. She kneeled down to be close to me and looked me in the face. “I think your brown skin is beautiful.” And I was better. That’s all it took — a simple statement uttered by one of the people I loved best.

Looking back, the story seems almost hackneyed, but it’s stayed with me as a reminder that a few words, sincerely spoken, can make a big difference to someone, and that words spoken with love have infinitely more power than those spoken cruelly.

What book(s) have made you see the world differently?

I grew up in suburban Sacramento. Life there was safe, sheltered, sterile, sunny, boring. What I searched for, from a young age, was a window into darkness. I first found this in Emily Bronte’s Wuthering Heights. I kept the book by my bed and flipped through it almost daily, starting every night on a different page, swaddling myself in its universe of death and ghosts and illicit love. I found the darkness again — delicious and disturbing, this time — in Toni Morrison’s Beloved. Both those books stayed with me as I graduated from reader to writer. Their prose is transcendent. I still turn back to them, all these years later, when I want to learn.

The Octopus by Frank Norris stayed with me for a different reason. I had to read it in high school. I didn’t finish it by the deadline. I did poorly on the test. I wasn’t exactly enjoying the book, but some stubbornness compelled me to keep reading long after my class had moved on. I finished it, and by the time I had, I began to understand how a book can take its time, that not every piece of literature dances tartishly for you in its opening pages, that sometimes a story inhabits its reader slowly. Moreover, I found that I’d grown to care deeply about an issue that had little direct connection to my own life — the impact of railroad development on wheat ranchers in 19th century California. There was no reason for me to connect with this book, and yet I did. It taught me the power of story, and in an important way, it lay the foundations for Lucky Boy.