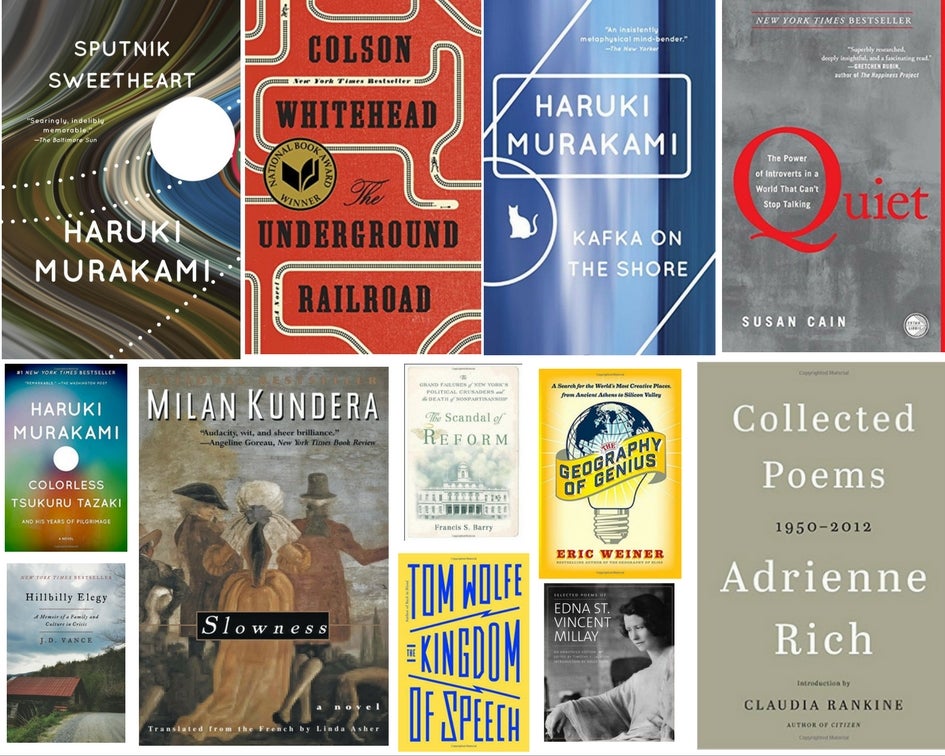

The Aspen Institute is a place of ideas. And what better place to find those ideas than in the pages of a good book? In December, our policy directors are sharing the books which had the largest impact on them in 2016. Read their recommendations below.

Adrienne Brodeur, executive director of Aspen Words:

Collected Poems: 1950-2012 by Adrienne Rich

Given the new state of the state, it’s been a balm to dive back into Rich’s prophetic and overtly political and feminist poems. With an introduction by Claudia Rankine, this collection is home to more than six decades worth of pioneering work, without which a good bit of today’s poetry would not exist.

Hillbilly Elegy, by JD Vance

I devoured this book in a single read. To me, it represents the best of memoir: An intimate look at a family – simultaneously heartbreaking and heartwarming – that also tackles something bigger and more universal. In this case, the economic, emotional, and spiritual anguish of a long-forgotten territory in the US, Appalachia, and its angry and overlooked citizens. A necessary read.

The Underground Railroad, by Colson Whitehead

This novel starts in the familiar but harrowing territory of traditional slave testimonies and then takes a turn toward magical realism when Whitehead places his protagonist, Cora, an escaped slave, onboard a literal underground railroad. The story shines its high beams on one of the darkest periods of American history, all while playing with the form of the novel itself. No. Small. Feat.

Mickey Edwards, director of the Aspen Institute – Rodel Fellowships in Public Leadership:

Selected Poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay, edited by Timothy Jackson

I thought I already had almost every poem written by, and book written about, Millay (even one of the short prose books she wrote under the pen name Nancy Boyd, which I found, as I recall, in a used book store in Dallas).

Years ago, I fell in love with a book called What Is To Be Done?, written in 1863 by Russian nihilist Nikolai Chernyshevsky, in which the main character, Vera Pavlovna, is an independent-minded woman whose ideas foreshadowed the modern women’s movement. Those ideas echo throughout Millay’s life and poetry. In her poem “Renascence”, written in 1912 when she was 19 (and a principal reason that she became, at just 31, the first woman to win a Pulitzer for poetry), Millay wrote these words: “A man was starving in Capri; he moved his eyes and looked at me; I felt his gaze; I heard his moan; and knew his hunger as my own.”

What a beautiful and haunting reminder of what our common humanity demands of us; I quote those words often in my speeches. How wonderful it was then to find this book, beautifully done, the only Millay book left in the poetry section of the William Faulkner bookstore in the French Quarter of New Orleans. Continual rediscovery is a great joy, and immersion in Millay is an eternal pleasure.

Quiet by Susan Cain and Slowness by Milan Kundera

There’s not much need for amplification: The titles say it all. Ours is a world of rush and noise and we are paying a dear price for it: A politics bereft of the nuance and calibration that come from deliberation and contemplation; decisions made on the fly and the costly clean-ups that inevitably follow when the unintended consequences come home to roost. To be fair, these books did not awaken in me any new perspectives about either of these assaults on our senses: I have always preferred quiet (or semi-quiet, symphony to jabber) and stroll. Cain’s arguments are compelling, and Kundera is, well, Kundera: a man who, like Michael Chabon, can fill a novel’s worth of reflection in a single sentence.

The Geography of Genius by Eric Weiner

The district that I represented in Congress, in central Oklahoma, had the worst “soil,” if you can call it that, on the planet. Hard, red clay. Just try burying fish bones in the backyard after cleaning the small-mouth bass you reeled in at a nearby lake. You’d need dynamite to dig the hole. In Massachusetts, my new home state, the challenge is planting a garden in ground that must contain every massive rock ever metamorphosized since the beginning of time. The fact is, it’s hard to get anything good to grow without proper soil, and sometimes you have to work pretty hard to develop that soil. The flowering of genius – great art, music, architecture, science, politics, technology – comes when the community’s soil (an openness to new thought, appreciative audiences, generous supporters, political space for free expression) is welcoming. Thus Florence. Thus Athens. Tech guys call this “garbage in, garbage out” – what you start with determines what you get at the other end. In economics, it’s the reward system – what you reward shapes what you get. Weiner points out that geniuses – and the advances that enhance our global community – flourish when the soil in which the genius labors is supportive of his or her efforts. Our problems, too, though Weiner doesn’t go there, are systemic: What we value determines what we get. Democracy, too, demands a proper soil. What kind of soil are we providing for our own society? Even though Weiner doesn’t ask these questions, his book makes it hard not to think about them.

The Kingdom of Speech by Tom Wolfe

Wolfe, ever the provocateur, takes on Darwin and Chomsky, the worship of opposable thumbs, and most of the theories as to what makes us – the human animals – superior to apes, lizards, and butterflies. The ultimate distinguisher, the one no porpoise can emulate, he posits, is human speech. It is the power of the word – the enabler of abstract thought, among other things – rather than evolution, that accounts for who we are as a species apart. Wolfe doesn’t denigrate the animal kingdom – this is not a screed against those who would be heedful of or protective of other animals – but it’s a distinct blow to the Chomsky crowd, and an immensely entertaining read.

Sputnik Sweetheart, Kafka on the Shore, and Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage by Haruki Murakami

Okay, so this is my weird side, talking cats and people crossing between dimensions. But Murakami fascinates. Few reviewers seem to think much of his plots or his writing. But I dare you to read one of these books through and have it slip from your consciousness when you’ve finished. These books are classified as “mystical realism” and that’s a good characterization if you’re into genre sorting. But the people – uniquely Murakami people – are lost in a sea of perplexity; we’re trying to make sense of the lives Murakami has given his characters, but they’re trying, too. If you’ve read Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and the Margarita – another strange book that lives with you long after you’ve finished it – you’ll have a sense of Murakami and how he has burrowed into so many minds.

The Scandal of Reform by Francis Barry

My own latest book, The Parties Versus the People, owes a tremendous debt to Frank Barry. In this book, about the havoc the Progressives of the late 1800s and early 1900s wreaked on American politics, Barry shows how “reformers” inadvertently set us on the path toward the extreme partisanship that is today making thoughtful governance almost impossible. I’ve long argued that “if it fits on a bumper sticker, it’s almost certainly wrong,” and Barry offers ample evidence that such skepticism is well-founded. With a sound dollop of reformist arrogance and a clear political agenda of their own, the progressives shoved American democracy into a deep hole in which we remain buried. This is not a feel-good book, but if knowledge is a prerequisite to extrication, Barry has provided the key.