On April 16, Aspen Words will confer the third annual Aspen Words Literary Prize, a $35,000 award recognizing a work of fiction that addresses a vital social issue. Sixteen nominees are still in the running, and the diverse list includes 12 novels and four short story collections covering a variety of critical issues and published by an array of presses. While the jury works on narrowing down this list to five finalists (to be announced February 19) and a winner, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, how they view their role as a writer in the cultural and political moment, and the best piece of writing advice they’ve received. You can find the series of conversations here.

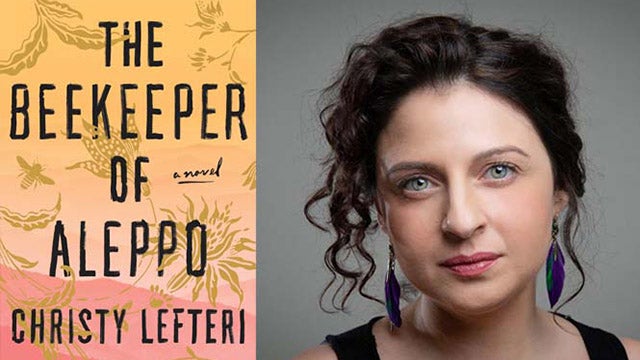

Christy Lefteri’s novel The Beekeeper of Aleppo, about a couple who must leave war-torn Syria and make the treacherous journey to the UK, brings faraway events that we see on the news close to home—and brings home the realization that the most ordinary of lives can be completely upended in unimaginable ways. The book was born out of Lefteri’s time working as a volunteer at a UNICEF-supported refugee center in Athens. She also is the author of the novel A Watermelon, a Fish and a Bible.

How do you view your role as a writer in this cultural and political moment, and why is the time right for your book?

When I write, I feel it with all of my heart. I immerse myself in learning, experiencing, and understanding as much as I can so that I can create an intimate relationship between my characters and the reader. In today’s cultural and political climate, I believe that this intimacy in fiction can have the power to evoke empathy and to challenge pre-existing beliefs, often exacerbated by the media.

We’ve all seen the images on TV, refugees desperately trying to cross seas and oceans in rubber boats. Yet, it is not unusual to become desensitized to these images. My parents were refugees, they found asylum in London after the war in Cyprus in 1974; I grew up in the shadow of their traumas, especially the unspoken ones. In 2016 and then again in 2017, I decided to volunteer at a UNICEF supported refugee center for women and children in central Athens. Perhaps because of my own family history, I felt compelled to help in any way I could. After spending some weeks working at the center, I began to realize that I had never really connected to the devastation I had seen on TV. The crisis imagery and the unspecific language which is often used to portray the experience of refugees in the media left me feeling numb. However, being there for people during the most horrific circumstances of their lives, moved me to tears and emotional exhaustion.

With so much negative discourse in society about refugees, with so many people seeking asylum around the world, I believe it is the perfect time for my book, in order to shed light on the often-devastating plight of refugees, through an intimate portrayal of one family—their losses, their fears, traumas, hopes, and their ability or inability to love each other because of these things. My role as a writer is to help the reader to walk in these characters’ shoes, to feel what they feel so that perhaps they can develop a deep empathy and understanding. I want The Beekeeper of Aleppo to represent all refugees worldwide. America is a continent of immigrants and refugees, yet the political climate is hostile to them right now. I think more than ever, we need fiction which helps us to not just see but to feel the struggles that refugees face in today’s world.

What other author deserves this award and why?

I think so many authors on the longlist deserve this award, but the novel which stood out for me was We Cast a Shadow by Maurice Carlos Ruffin. What underpins this disturbing satire is the love that a father has for his son, and how that love is tainted and distorted by the racist society in which they live. Although dystopian, it chillingly sheds light on racism in today’s world. Through humor and absurdity, it raises some of the most important and pressing questions that we face today. What made this book so powerful for me was that although I found myself laughing, I was at the same time confronted with a very dark reality that echoed and reflected the world in which we live. For a while, I lived in the shoes of this father, I heard his reasoning, I saw what surrounded him, how society swallowed up his soul. It had me reeling with laughter and fear. It is a special novel that can evoke such contrasting emotions. I want to pass it on to every person I know and say: Do not be complacent! Look what we are! Look what we can become!

What is the core tenet of your book’s philosophy?

The underlying philosophy of my book is related to the human condition, to loss and to our ability or inability to grieve—something which we have all felt at some point in our lives. When the trauma of losing their home, their safety, their family, and their son is too much for Nuri and Afra to bear, they become lost in their own world of darkness. And they have forgotten how to love each other. It is only when they are able to cry or grieve for their son that they are finally able to reconnect with life and with one another. When I met people in Greece and saw how much they suffered, I began to realize that real hope and resilience lies in being able to mourn for what we have lost and reconnect with the people who are still by our side. This is precisely why I chose to structure the story the way that I did; the reader knows from the start that the characters make it to the UK, but they do not know what will happen to their minds and their hearts and whether they will find their way back to one another again. We cannot change the past, we cannot get rid of our traumas, whatever they may be, but we can find a way to love the people who are around us.

This is a story about loss and hope, about losing our sense of safety, the place that we call home. It is about losing our sense of self, amplified by displacement and migrating, losing our identity, becoming known only as a refugee. I wanted the reader to get to know Nuri and Afra as people with their own complex emotions. People that any of us could be.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

If I wasn’t a writer I would be an artist and use color instead of words.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve received on writing fiction?

“Let yourself feel and let yourself be free when you’re writing.” This was a bit of advice I was given by a screenwriter I met on a flight on my way to Athens. I was feeling stuck at that point, bogged down with how I thought the story should develop, essentially restricting myself. Although the advice felt abstract, I took it on board and the narrative grew and blossomed in ways that I wasn’t expecting.