Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has brought a new intensity to debates about business and the transition away from fossil fuels. With the price of oil and other commodities rapidly rising following the disruptions of the war, demand for sustainable funds waned even as some commentators predicted the war would prompt a shift toward greater use of sustainable energy.

As extraordinary as the current moment is, the contrasting news stories are arguably emblematic of the media landscape of recent years. Stories about surging investment in Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) funds run side-by-side with warnings of the near-certainty of drastic climate change. Under such circumstances, clarifying the who, what and how of combatting climate change is critical—especially for business leaders seeking to rise to the challenge.

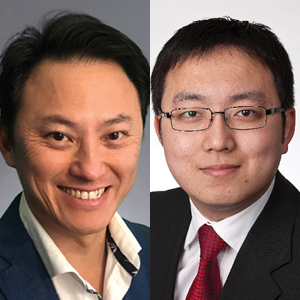

Achieving clarity on climate change solutions is central to Kingsley Fong and William Wu’s creative pedagogy, recognized with an Aspen Institute Ideas Worth Teaching Award for their course,“Sustainable and Responsible Investing.” We spoke with the two professors at the University of New South Wales Business School in Sydney, Australia about how they’re preparing students to make real shifts in the financial system, and what they see as the questions business should be weighing at this historic crossroads.

![]()

Traditional finance courses often treat the curriculum as removed from broader issues such as environmental and social factors. Why was introducing atypical pedagogy, like regular blogging and other creative assignments, into your course important, and what do those differences bring to the finance classroom?

We design the pedagogy to help students understand critical environmental and social considerations and imagine how to incorporate them into governance arrangements, investment decisions, and financial product design. Regular blogging allows students to make their mental model explicit for reflection, e.g., on the purpose of business and investment practices and how they may be reinterpreted or revised to achieve a sustainable economy. It helps them think about foreign environmental and social concepts in familiar financial language and new non-financial dimensions.

This active learning experience is critical to expanding their operating mental model and investing in three-dimensional costs and benefits: financial, environmental, and social. Analytically, investment decisions with non-financial considerations involve more judgments inside and outside of economic models than in a traditional investment course. A critical evaluation of the arguments and evidence of hypothetical relationships informs these judgments. Blogging gives students the freedom to research and develops their expertise in an area they find intrinsically motivating.

The group assignment allows students to demonstrate their learning and research by working together as a responsible investment team to evaluate companies in a sector. By rating firms on company conduct and impact, adjusting financial forecasts and discussing corporate engagement, they practice the building blocks of responsible investing approaches. Students also perform a concise pitch of their findings and respond to questions, preparing them for advocacy.

The conversation about the role of divestment vs. corporate engagement in ESG investing has evolved and become more nuanced over the past two years. How do geopolitical conflicts—like the war in Ukraine—cloud or add clarity to this debate?

Corporate engagement aims to influence behavior by communicating investor concerns. It requires the rule of law, respect for facts, and concern about social pressure. Divestment sends a clean statement that unethical activity is not tolerated. It is often used after failed engagement efforts. Divestment may change corporate behavior by raising the cost of capital if enough investors divest and the company needs finance. It also results in investors less concerned about unethical activities becoming the owners. They earn a higher return by buying at a depressed price but bear higher political risk and illiquidity.

The unfolding Russian conduct in Ukraine points to the lack of any critical condition to pursue corporate engagement to change the Russian position in the war. For ethical actions, divestment is the only option. Would it make sense to sell Russian assets at a low price to those who care less about the unfolding atrocities? The potential for further deterioration in the value of Russian assets because of sanctions and Russian retaliation may provide the needed additional financial risk to exit.

Regarding the fossil fuel industry, we have seen divesting has only meant those assets changed hands. Whether the assets are transferred to a different vehicle, attract different types of investors, or go into private hands, there is less reporting, measuring, and monitoring, which adds to a net negative. Furthermore, the war results in elevated commodity prices, which means fossil fuel companies have plenty of cash. This medium-term trend severely limits the ability to use divestment to change their behavior. Hence, we argue that engagement with fossil fuel operators on a science-based approach towards net zero emissions makes more sense.

While companies, consumers, governments, and regulators all have a role to play in the transition to a net zero economy, how do you hope this course will prepare your students to make real shifts in the financial system?

We support real shifts in the financial system by equipping students with time-invariant principles, exposing them to ways of integrating non-financial considerations into investment processes, and helping them to develop advocacy skills. We clarify the objectives, motivation, science, and methods of responsible investing so students can focus on long-term system transition. That clarity is critical for assessing innovations and cutting through distracting debates, overlapping terminologies, denials, delay, and greenwash.

In the environmental dimension, we use the planetary boundary framework to demonstrate the finiteness of natural resources and the urgency to address climate change and biodiversity. We refer students to the source, IPCC, for the severity and irreversibility of climate change. Although climate science is complex and interdependent, climate actions to cut emissions and halt deforestation (which is also key to biodiversity) are clear.

In the social dimension, we take a systemic view of the economic machine and realize that everyone has control over four of the five levers in the system: consume, invest, work, and vote. We are all responsible for the transition to sustainability. The course also assesses the effects of diversity, modern slavery, and human capital management. In governance, we evaluate directors’ skillsets, independence, and remuneration to reflect their climate change capability and intent. We emphasize that consumer trust and accurate marketing of responsible investment products are critical. We highlight the power and limitations of specific responsible investment strategies, both to avoid the damaging effects of greenwashing and to develop taxonomies to address the issue.

Finally, we provide opportunities for students to connect to a diverse set of responsible investment professionals. They learn about responsible investment in roles such as analysts, portfolio managers, chief sustainability officers, bankers, and activists at fund management firms, pension/superannuation funds, rating agencies, banks, and NGOs.

As alumni from your course go into leadership positions across industries and sectors, what is the one lesson that you hope will stick with them throughout their careers?

We are connected, and human actions determine the path of life (social and biological) and earth (planetary composition and climate trajectory) through our wants, responsibility, technology, and systems. Environmental, social, and financial perspectives are three interrelated ways to see the consequences of human activities. Costs and benefits come in triplets and over time. Life needs a stable natural environment and habitat to flourish.

It can be overwhelming, but sustainability leaders have many supportive peers. Purpose attracts talents that innovate and create values. People ultimately prize meaningful relationships over materials and status. Power and wealth are the means and not the ends. Take a deep breath and exhale slowly with a smile. We need leaders with healthy minds that communicate clearly in order to awaken more people to the holistic vision where present and future generations thrive on a beautiful earth.

![]()

Interested in more innovative insights for business education? Browse our complete collection of interviews with outstanding educators, and subscribe to our weekly Ideas Worth Teaching digest!