Varun Sivaram is the Douglas Dillon Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations, where he directs its Program on Energy Security and Climate Change. He is scheduled to speak at the Aspen Ideas Festival on accelerating energy innovation and developing new strategies to confront climate change. The views and opinions of the author are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Aspen Institute.

Recently, the idea that renewable energy sources—like wind, solar and hydroelectric projects—could meet all of our energy needs has grown in popularity. Earlier this year, Senator Bernie Sanders and others unveiled a bill to transition the United States to a 100-percent renewable power grid by mid-century. They grounded the feasibility of their idea in an academic study by Stanford Professor Mark Jacobson and colleagues, who argued in the prestigious pages of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that wind, water, and solar energy could supply virtually all of America’s energy needs.

Unfortunately, that paper is misleading. That’s the conclusion of a new article in the same journal, released today, that I co-authored with twenty of the scholars I respect most in the fields of energy science, economics, and policy. With today’s technologies, we argue, a 100-percent renewable energy future is an expensive fantasy. And belief in that fantasy can motivate damaging public policy choices, like cutting off support for non-renewable but equally clean sources of energy, like nuclear power. By contrast, the prudent course of action is to keep every option on the table and add even more exciting technology options by investing in innovation.

The original paper by Jacobson et al. envisions a radically different future for the United States. In it, solar panels and wind turbines would pump out massive quantities of electricity. But because these sources of energy are only available when the sun shines or the wind blows, hydroelectric power plants around the country would kick in to compensate for lulls in solar and wind power, and enormous deployments of storage technologies would squirrel away excess energy for later use. There would even be enough electricity to power the production of hydrogen fuels for cars, trucks, ships, and planes. In this rosy future, fossil fuels would be completely eliminated, and all nuclear reactors would shut down as well.

But by calling this a “low-cost solution,” Jacobson et al. overstate their conclusions. As a result, they dress up what is in essence a provocative piece of science fiction as a serious resource for policymakers to make decisions.

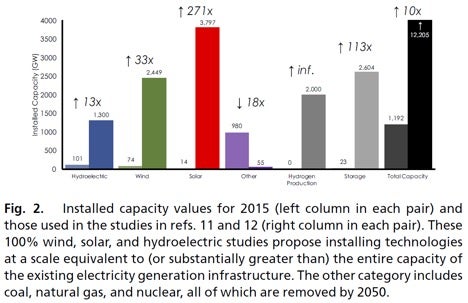

In fact, their proposal would be astronomically expensive and complicated (as the figure below from our paper illustrates). It would require adding hydroelectric generation capacity equivalent to six hundred Hoover Dams. It would entail deploying over a hundred times as much energy storage capacity as currently exists in the United States by using barely-tested technologies like “phase-change materials.” It would take trillions of dollars of investment in new electricity transmission lines and infrastructure to produce, transport, and store hydrogen. And it would demand an expansion of solar and wind power capacity well in excess of any buildout of power plants that the world has ever seen.

If policymakers buy into this far-fetched vision, they might make choices that make a clean energy transition even harder. And such a transition is urgently needed. By 2050, global carbon emissions from the electricity sector will need to plunge to nearly zero in order to give the world a shot at averting catastrophic climate change. Developed countries like the United States are best placed to lead the charge toward that target and set an example for the rest of the world to follow.

But by targeting a future powered only by renewable energy, US policymakers would tie one hand behind their backs as they confront an already daunting challenge. They may see little reason to prop up nuclear reactors that are closing down at an alarming rate, even though nuclear power is America’s largest source of clean energy. And, expecting the demise of fossil fuels, they might fail to invest in technology to capture and store the carbon emissions from fossil-fueled plants.

Indeed, the biggest mistake policymakers could make would be failing to invest in a range of new energy technologies, lulled into complacence by studies, such as the one by Jacobsen et al., that argue that existing technologies are all we need. To be sure, the costs of solar and wind power have fallen dramatically and look set to continue doing so. But much more will be needed for a clean energy revolution.

For example, next-generation nuclear reactors could be both cheaper than existing ones and meltdown-proof, providing a reliable source of clean electricity. And advanced materials to harness sunlight and convert it into hydrogen fuels might provide the copious hydrogen called for by the Jacobson et al. study to replace petroleum fuels.

By investing in the research, development, and demonstration of these new technologies, policymakers could spur innovation that closes the gap between a science-fiction clean energy future and reality. And until that happens, they should focus on increasing, not decreasing, the number of options at hand.