Catherine Geanuracos is the CEO of govtech startup CityGrows, a low-cost self-service cloud-based operating system for local government. She serves on the Los Angeles Mayor’s Technology Council and helped launch the City’s Innovation Fund as Vice President of the Los Angeles Innovation and Performance Commission. She’s Board Chair for CicLAvia, the largest open streets bicycle event in North America, and board member/ co-founder of Silver Lake Forward.

This interview is part of the Aspen Institute Center for Urban Innovation’s series of conversations with inclusive innovation practitioners.

Jennifer Bradley: How do you think about the relationship between tools and values?

Catherine Geanuracos: I helped organize the first meeting of the “Union of Concerned Government Technologists” last year, which was an unofficial convening of people working in government and civic tech at the federal, state, and local levels. We looked back to a set of open data principles released in 2007

by Tim O’Reilly, and about 30 other people–only one of whom was female, but that’s another story.

Catherine Geanuracos, CEO, CityGrows

We asked, looking at them now, what was missing, what do we know now, what can we do to improve things going forward? We had a great conversation about how the context in 2007, and the people in the room, and their personal goals influenced this set of purportedly neutral values about how and why open data should work in government.

There was a belief then that open data in and of itself would solve a lot of problems in government and civic participation. But, as with anything related to technology, or tools, or tech, it’s all about the context, and the way things are implemented, and the values surrounding them. You can be theoretically very open in the data that your government releases, but not actually share anything that’s useful or actionable. The potential benefits of open data are determined by who is using it, and what the goals are, and what the motivations of the people releasing it are.

The conclusion that I came away with is that there are multiple sets of values operating for technology in the public sector that we didn’t understand in the early days. Sometimes those values are in conflict with each other. Often there are multiple actors in the government tech space that don’t really share the same values, but that isn’t usually acknowledged. Some for-profit companies operate with a system of values that put company metrics ahead of the public interest, for example, and some governments value stability over efficiency or accountability.

Plus there are whole new areas for which we need values and principles. For example, there was nothing anywhere in those original values around accessibility or representing the diversity of communities. There’s so much potential to using data and technology to improve public participation and increase inclusion and promote equity, but in and of itself, it won’t do that unless it’s guided by a set of community-driven values.

JB: Which tools do you use in your practice?

CG: Well, it depends on which part of my practice. I’ve chosen to co-found a technology company that works with local governments to increase the efficiency and transparency of local government. So I believe that creating the right sort of tools can improve trust, increase participation, improve accountability, increase representativeness, all of those things.

In the non-profit advocate roles that I have, whether it’s with CicLAvia or other local projects that I work on, I use everything that is at our disposal, whether that be publicly accessible data, social media platforms, or Nextdoor. We also use real-world tools like making public comment at community meetings and gathering petition signatures at local farmers’ markets and school events. I use anything I can, and test and iterate.

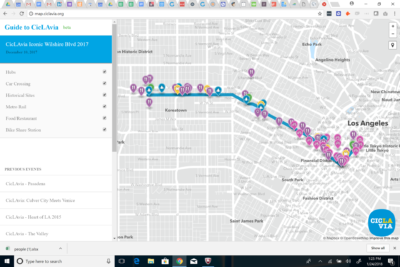

When it makes sense, we build new tech to support community engagement. For CicLAvia, we built a mobile-first, open source mapping tool for open streets events. We created the tech using open source tools so that any other open streets event in the world can “fork” or, adapt, the code and make it useful in their cities.

CicLAVia Iconic Wilshire Boulevard, Guide to CicLAvia

It’s useful not to bring too many biases to the question of, “Could this be a useful tool for my goals or project?” There are technologies that maybe were not created specifically for increasing participation or awareness that we should leverage as aggressively as we can. We should also recognize where we need to create something new.

Just ask yourself, “Does this tool align enough with my core values that it feels accessible for me to use it?” And then test it out and see if it works. And then if it works, keep using it. If it doesn’t work, then you don’t keep using it, and that’s okay. And your tools might not be the same over time.

JB: Which tools do you not use?

CG: From my public innovation commissioner experience, I feel that there are some technology vendors to government who aren’t necessarily always acting in the public interest. There’s a huge amount of waste in technology, and there are individual technologies that I don’t think are a good use of resources because they’re either expensive relative to the benefit they bring or difficult to manage. I think we should be holding vendors accountable to the bigger picture of their impact on the public sector.

There’s a set of values that I believe governments and non-profits should be using when they decide which technologies to purchase, or use, or implement–like thinking about the true lifetime cost of using a piece of software. There is some stuff that is not a good bargain, and some things that don’t align with broader values around transparency and participation. If things don’t pass a community’s values test, then they shouldn’t get used. I’ve proposed a set of those values for govtech–but every community needs to decide which values are most important to them.

JB: What is a tool that you wish existed, but doesn’t?

CG: Can we get closer to direct democracy? There are blockchain startups like Democracy Earth/Sovereign in Latin America and Flux in Australia that are experimenting with how to connect constituents to government in new ways.

In the nearer term, we have to think about all the ways that people interact with content and issues now. Different people are clustered on different technology platforms, and in different places. One of the things that we worked on with the “Angels Lab” civic engagement working group in the city of LA was drawing in people who are not currently participating at all. Those people are usually younger, of color, lower income so they have less time to participate in public meetings; they are parents so they have less time because they’re dealing with childcare issues. Getting the voices of those people into public discussions is really important.

Having something that makes it easier for governments to go out and find those people and actively engage them, rather than relying on the traditional perspective of government waiting for people to come to them, which privileges people who have time, energy, money to do that, and therefore yields perhaps not the most representative view, is really important.

JB: How should we think differently about tools?

CG: From an inclusion perspective we should be a little bit more opportunistic, and a little more willing to engage tools that arise unexpectedly, outside of an officially sanctioned role. For example, cities and officials who are using Nextdoor to communicate with their constituents are reaching a different set of people than people who’ll sign up for emails. That means being opportunistic, strategic, and proactive and recognizing those gaps when they exist. But it can be exhausting and time-prohibitive to be active in so many places, especially when the impact can be difficult to quantify.

Sometimes the tool will have to come from the public sector to really represent the public’s interest. The tool for inclusion and public participation might be analogous to a utility, or the fire department. It might not ever be profitable, so is it incumbent on government to build something specifically for the public, which is designed to be replicable and used over and over again?

JB: Is there anything else you think people reading this should know that the questions that I’ve asked so far did not elicit?

CG: We should be working towards an ecosystem of technology providers, developers, constituents and users of those technologies, commissioners, and administrators of the technologies, and a set of evaluation rubrics to make sure that stuff is happening in the public interest if it is being done with public funds. Far too often we’ve seen public money go to contracts that don’t put the public interest and the public good first.

We have to create guidelines and guideposts so that we make sure government and civic participation work as equitably and inclusively as possible, because if we don’t do that our latent and blatant biases will just get replicated.

This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

This blog series is supported by the Citi Foundation, a vital early supporter of the Center for Urban Innovation at the Aspen Institute. With the Citi Foundation’s help, the Center convened leading-edge practitioners to develop a shared set of principles to guide a cross-sector approach to inclusive innovation in low- and middle-income neighborhoods, and to determine how the Aspen Institute could support this practice.