Rich Luker operates Luker on Trends which focuses on building fan relationships and engagement. He conducts research to understand how American free time is changing and impacting the sports fan experience. Luker on Trends’ flagship product, the ESPN Sports Poll, has been the industry standard for understanding American sports fans since it launched in 1994. Luker will be a panelist at the 2017 Project Play Summit for a discussion titled, “From Pokemon Go! to esports – Lessons and Opportunities.”

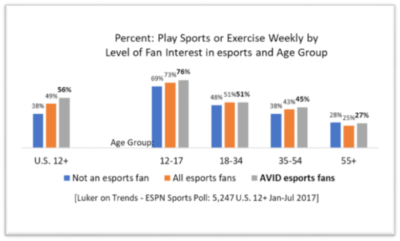

Let me start with something really positive about esports before considering some thornier issues. A larger proportion of fans and AVID fans of esports participate in sports and/or exercise on a weekly basis than those who are not esports fans. Esports fans are NOT game-chair-potatoes. I will come back to this after taking on some fundamental questions about esports.

Our panel at the Aspen Institute’s Project Play Summit is titled “From Pokemon Go! to Esports – Lessons and Opportunities.” Actual sports video games like Electronic Arts Sports’ Madden and FIFA fit somewhere between the two. Playing sports video games actually precedes becoming a fan for many people.

An important distinction is what follows from playing online or a video game. Conventional sports video games are potentially three-stage engagements. Stage one: You play the online/video game. Stage two: You become a fan of that sport. Stage three: You play the game in real life. With esports (of the sort found on Twitch), there are really only two stages – playing the computer games and being a fan of the pros who play those games. It is not clear which comes first.

Going forward, on the present course, esports will have to find an entirely new player and fan base roughly every 15 years because kids stop paying attention and playing long before they become parents. They are not going to pass it on to their kids. That would be like you passing along Pac-Man to your kids.

The difference between esports and generationally linked sports can be found by Googling “St. Louis Cardinals tattoos” and looking at the images. Sports didn’t put those tattoos there. MLB didn’t do it. Nor did the Cardinals. A generations-long, family-based love of the game and the team became so strong that it became part of a life-long identity.

Fans build sports. Sports don’t build fans. Fans make businesses money. Businesses don’t keep fans.

Are esports really sports?

For nearly 25 years, Luker on Trends – The ESPN Sports Poll has been monitoring sports engagement in the United States on a nearly daily basis. We study and are asked about everything from the NFL to sport stacking. We have been studying esports since 2011, more intently since 2015, and on a daily basis this year. Among the most common questions people ask about esports: “Is it a sport?”

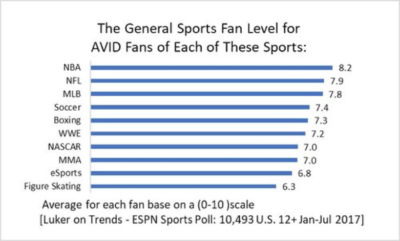

The table on the left shows the average, overall, general level of sports interest for AVID fans of 10 sports. We define AVID as fan behaviors that are statistically significantly above the national average. The more important sports are to a fan, the more they will engage in typical sports behaviors (playing, watching, attending, following, having favorites, wearing licensed products, spending, supporting sponsors) for any sport they follow.

The table on the left shows the average, overall, general level of sports interest for AVID fans of 10 sports. We define AVID as fan behaviors that are statistically significantly above the national average. The more important sports are to a fan, the more they will engage in typical sports behaviors (playing, watching, attending, following, having favorites, wearing licensed products, spending, supporting sponsors) for any sport they follow.

The average level of general sports interest of AVID esports fans is above AVID figure skating fans, but below the rest of the 30 sports we track. The four sports at the bottom of the chart are the ones most likely to be challenged as legitimate “sports.”

Who are the fans of esports?

The esports fan base is younger, 62 percent between the ages of 12-34. It is also quite diverse, particularly under the age of 18, where just over one-third of AVID fans are white (there are more Hispanic youth).

The esports fan base is younger, 62 percent between the ages of 12-34. It is also quite diverse, particularly under the age of 18, where just over one-third of AVID fans are white (there are more Hispanic youth).

But the link between esports and play is not just youth. Controlling for age, esports fans from 12-55 are more likely to be active in sports or exercise than non-fans.

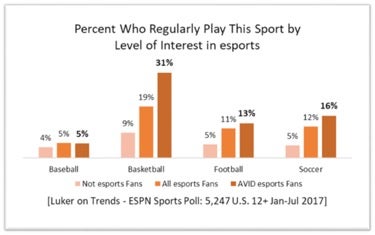

The more interested a person is in esports, the more likely they are to currently play the major sports regularly. But here, the underlying characteristics of the esports fanbase impact the results, with youth, and the higher percentage of minorities, adding to greater play of basketball and soccer. More esports fans are active in sports, but what is the connection between esports and an active life with active play?

The value of esports is not the kind of play Project Play is trying to foster.

This is a business, a sports business. It has grown to the size it is today because there is fan demand that can lead to media revenue, not for financial gains off esports players. There are over 75 million esports fans, over 13 million AVID esports fans in the U.S. in 2017 (LoT-ESPN Sports Poll). This is not the first time since 2000 that a new, or fringe, competition has caught fire. There may be lessons to learn from the last one: poker.

The poker explosion began in 2002 when ESPN first showed the cards of players. Chris Moneymaker won the World Series of Poker in 2003. It seems like everyone in America got a poker set as a holiday gift that year. I got two. Poker series were showing up on the most unlikely of television networks, like the Travel Channel. It was tempting to think there were no limits to the future and growth potential. As fast as it grew, it fell. It was a three-year run. What happened?

Very few people realized that 25 percent of Americans play poker. Being able to see the players’ cards literally changed the game. Poker players watched, but for a short-lived reason. They wanted to improve their play. They watched until they didn’t feel like they were learning any more. Then they didn’t watch any more.

In the same way that poker players were the dominant poker fans, video game players are the biggest esports fans. While 24 percent of those 12 and under in the U.S. are fans of esports, 54 percent of game players are fans and 17 percent of those do not play video games.

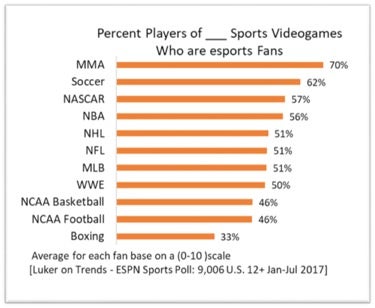

When looking at esports interest by the kind of sports games video-game players play, the lowest is 33 percent of those who play a boxing video game are fans of esports, and the highest is MMA at 70 percent. Which brings us to playing versus fighting. The vast majority of games that are making esports a business, are combat games. That is not likely to change.

When looking at esports interest by the kind of sports games video-game players play, the lowest is 33 percent of those who play a boxing video game are fans of esports, and the highest is MMA at 70 percent. Which brings us to playing versus fighting. The vast majority of games that are making esports a business, are combat games. That is not likely to change.

What kind of active play life can esports promote?

Perhaps, this is the most important issue for us to discuss. Sports video games (football, basketball, etc.), have a role in promoting the broader sport. Before 2010, our data indicated that sports video games were having no impact on engagement with the underlying sports. Video-game players were not sports fans. They were video-game players. The games were still raw enough back then that the best players were the best because they understood the programming, not because they understood the context of the game. How else would you know to swat a cloud to get a reward in Mario Brothers, or to always run a full blitz against a fullback sweep in “4th and Inches”?

By 2010, not only had the programming gotten much more sophisticated, but the knowledge of the game was spot on, and detailed. For the first time, in 2011, we saw substantial numbers of people playing a sports video game before becoming a fan of the sport. Specifically, 37 percent of those who played EA’s FIFA said they played the video game before they became a soccer fan.

One of them, Wes, is now an associate at Luker on Trends. Surprisingly, in 2012, 17 percent of those who played Madden said they played the game before they became an NFL fan. We know a video game can produce fans (which is what the business needs). The samples are too small for us to say sports video games are producing PLAYERS – though Wes tells us he took up playing soccer as well as becoming a fan. And he still plays.

Is the primary media business value of esports to serve people who want to play esports better?

If so, that translates into a short lifetime value. Though people play video games into their 40s, the best of the pros burn out in their 20s. New games come online continuously, making it harder to pass the love to the next generation.

Among the arguments against games like poker, sport stacking, and esports being real sports is the lack of legacy. Poker comes the closest to having generational transfer potential. Part of the poker craze last decade was because a lot of teens and 20s played poker with their parents AND grandparents (the biggest reason they gave: “I like to take their money!”). Poker was, by far, the biggest multi-generational activity at the time. In fact, one of the least valued, but most powerful, strengths of sports you actively play is a free-time love that is part of your family history. Where do esports fit in that picture?

I conclude with these thoughts and questions:

- Forty percent of 12- to 17-year-olds today say they spend “most of the day” online. Tech games are the present, and will only be bigger in the future. But what values do they serve? Clearly, they enhance reaction time, they are fun, and they are profitable as entertainment, for now. But how do esports contribute to the need for more physically active lives for children, or promoting multi-generational engagement?

- FIFA and Madden prove video games can create fans. They are not creating fans for Madden. They are inspiring people to be NFL fans, and people like Wes to PLAY soccer. The vast majority of esports games engage in combat. Is that what we are fostering here? What is the natural, active living-out of a combat game?