Aspen Words will confer the inaugural $35,000 Aspen Words Literary Prize this year, recognizing a work of fiction with social impact. Twenty nominees are still in the running, and the diverse list includes 12 novels and eight short story collections covering a variety of critical issues and published by an array of presses. While the jury works on narrowing this list down to five finalists and a winner, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, the importance of fiction in understanding contemporary issues, and the books that have influenced them most.

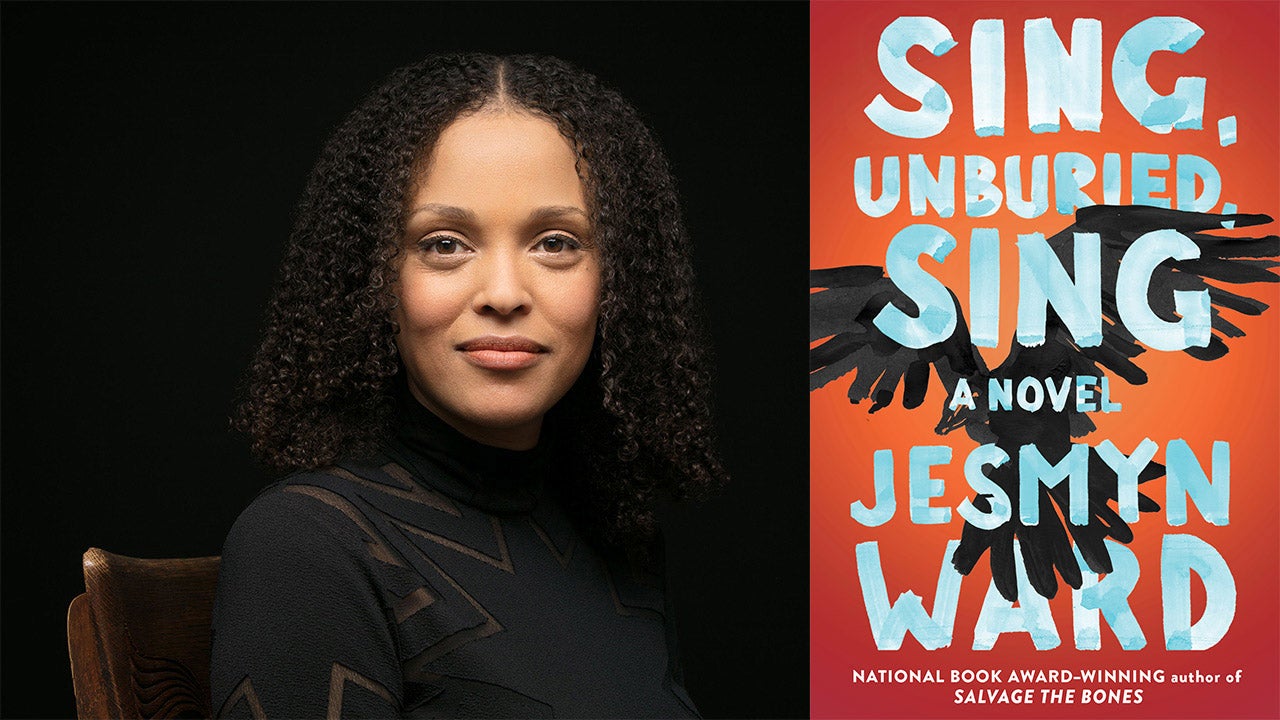

Sing, Unburied, Sing is Jesmyn Ward’s award-winning novel about an African-American family in Mississippi facing challenges around race, drug abuse, identity, and ancestral legacies. The story follows Jojo, a 13-year-old boy who takes a journey with his sister and black mother, Leonie, to collect his white father, Michael, from Parchman prison. Ward is an associate professor of English at Tulane University and 2017 recipient of a MacArthur genius grant.

Why did you write Sing, Unburied, Sing?

I’m always thinking about race, the legacy of the South, and the ways that black people survive when I’m thinking about an idea for a novel; those are the concepts that animate all of my work. But for Sing, Unburied, Sing, in particular, it was the characters that drew me forward — Jojo, really, who I saw very clearly before I saw any of the rest of the story. He was so compelling to me that I had to write about him, and then I also wanted to explore the issues that he struggles with, how he’s a mixed-race boy working to become a man in the contemporary South with all that brutal history riding alongside.

What was the most challenging thing about writing this book?

I’ve always been drawn to big, mythical elements in my writing; I was thinking about Medea while I wrote Salvage the Bones and The Odyssey while I wrote Sing, Unburied, Sing. At the same time, though, I’d never written anything but realism before this novel, and it was difficult to give myself permission to create a fantastical element in the story. That was my first and my biggest challenge.

How might fiction help us to explore contemporary issues?

I’m a writer, but I’m also living in this world and responding to what I see and experience and read about. It’s almost impossible for my writing, I think, or anyone’s writing, not to explore contemporary issues. Because I’m a black writer, and because of the legacy and present of racism and racist violence in this country, all my work engages with contemporary issues whether I like it or not.

What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

I was an obsessive reader when I was young, and I think I first learned language had power through reading: The books I loved were expansive and fantastical and set my imagination alight. But I was also exposed to racism as a very young child, as most black people are in the United States. The cruelty of some of the racist remarks I heard then marked me very powerfully.

What book(s) have made you see the world differently? How?

Like I’ve said, reading was my escape as a child – and particularly fantasy books like The Hero and the Crown and the Narnia series. They opened up a magical world for me, a world of imagination and adventure, and since I was particularly drawn to books about independent girls, they showed me the kind of person I wanted to be. As I grew up, older black writers like Alice Walker, James Baldwin, and Toni Morrison proved to me that I could exist on the page, as I was, in a uniquely important way. Some of the research I did for Sing, Unburied, Sing, particularly Worse Than Slavery by David Oshinsky, helped me really see our shared history for what it is, in all its brutality – and some of the research I’m doing for my current novel has taught me about the slave trade in a similar manner. Almost everything I’ve read has shifted or opened up in my perspective in some way.