Walter Isaacson says that greatness comes more from creativity than from genius. His biographies have cataloged the lives of Albert Einstein, Benjamin Franklin, and Steve Jobs —men who found patterns among the many fields they studied. In his latest work, Isaacson decided to document the life of Leonardo da Vinci, “the ultimate embodiment of someone who combines the arts and the sciences.”

At his book talk, the president and CEO of the Aspen Institute was quick to point out that Leonardo did not possess superhuman processing powers. He was simply a man on a quest to understand the world around him. His curiosity allowed him to create works of art that were not only beautiful, but also realistic. The following paintings, detailed in the book, illustrate Leonardo’s journey as both a scientist and artist:

The Baptism of Christ (c. 1472-1475)

Leonardo was born out of wedlock. Had he been a legitimate child, he would have taken over his family’s notary business. His status also excluded him from a classical school like other sons from the upper middle class. Instead Leonardo became an apprentice to Verrocchio, one of the finest artists in Florence. The Baptism of Christ was a collaborative effort between the two men, with Leonardo painting the young angel holding Jesus’ robe. Isaacson noted that this angel is much more expressive than the other figures in the painting. Leonardo also contributed the scientifically accurate ripples of water that pool under Jesus’ feet.

St. Jerome in the Wilderness (c. 1480)

At the beginning of his anatomy studies, Leonardo painted St Jerome in the Wilderness. While the artist had not completed many dissections at the time, experts have noticed that painting displays detailed knowledge of the skeleton, muscles, and nerves. Using state-of-the-art multispectral infrared technology, we have recently learned that Leonardo did not get the neck muscles right the first time — instead, he came back to the painting two decades after he began in order to perfect it.

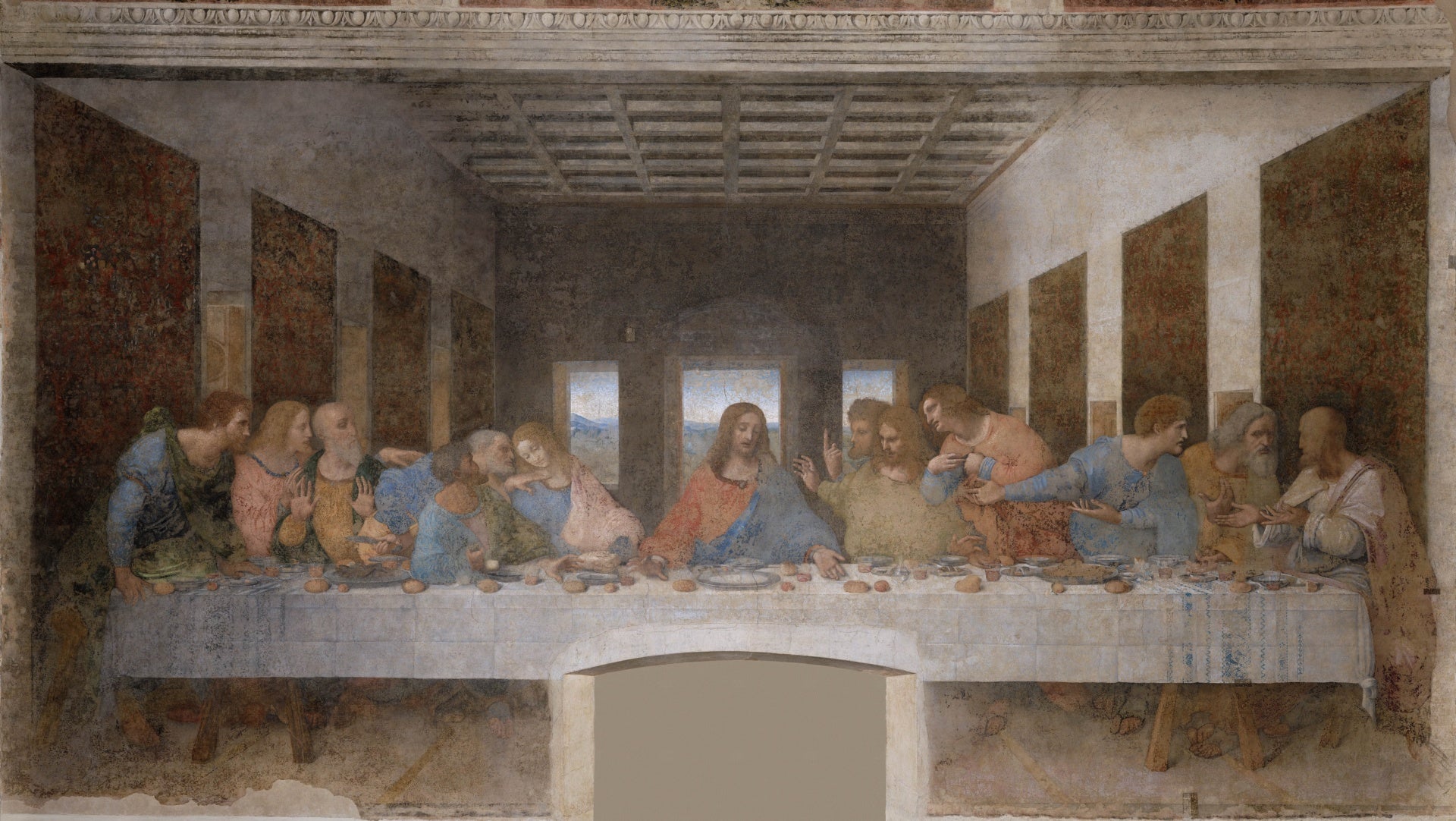

The Last Supper (c. 1495-1496)

The Last Supper was a mural commissioned by Ludovico Sforza, duke of Milan, and housed in the refectory of the Convent of Santa Maria delle Grazie. The painting is a dramatic narrative. Unlike other Renaissance painters, Leonardo was disinterested in creating still life works. The expressions on each apostle’s face are meant to display the ripple effect of Jesus’ announcement that one among them would betray him.

The painting also shows evidence of Leonardo’s past as a stage designer. The accelerated perspective of the lines makes the room look deeper. And because Leonardo was acutely aware of the placement of a window in the refectory, he painted the wall on the right as if light window had filtered into the room during lunch time.

Mona Lisa (1503-1506)

Perhaps the most famous painting in the world, the Mona Lisa is a portrait of Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a Florentine silk merchant. Leonardo’s notebooks show that he began drawing her smile while dissecting a human face to learn how the muscles of the lips worked. “Had he not done the science, I don’t think he would have had a feel for the patterns of nature,” Isaacson said.

While much has been written about Mona Lisa’s smile, it was Leonardo’s study of optics that allowed him to create this interactive work. Leonardo used his knowledge of the human retina to paint a smile that changes depending on where one looks. If you stare directly at it, it disappears. But if your eyes drift to her chin, cheek, or forehead, your peripheral vision picks up on the shadows and colors of the painting, revealing a slight smile.

Salvator Mundi (1506-1513)

Salvator Mundi recently made a splash in the art world when it was unveiled by Christie’s to be auctioned next month at a starting price of $100 million. The painting is the only Leonardo work in private hands and was authenticated very recently. Like his earlier works, Leonardo used the sfumato technique to create softened lines around Jesus’ face and robes. The lines of his hands that appear closest to the viewer are sharpest. The sale of the painting has also reignited the debate over why the robes behind the orb in Jesus’s left hand are not distorted. Isaacson believes this was purposeful — Leonardo’s notebooks reveal his knowledge of how glass would warp any object behind it. Isaacson’s favorite explanation is that Leonardo was indicating that Christ is miraculous.