In November, Aspen Words announced the longlist for the fifth annual Aspen Words Literary Prize, a $35,000 award recognizing a work of fiction that addresses a vital social issue. The selected books explore questions of freedom and identity, exile and belonging, and are set against the ravages of colonialism, consumerism, and classism. While the jury works on selecting a shortlist, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, how they view their role as a writer in this cultural and political moment, and the best piece of writing advice they’ve received.

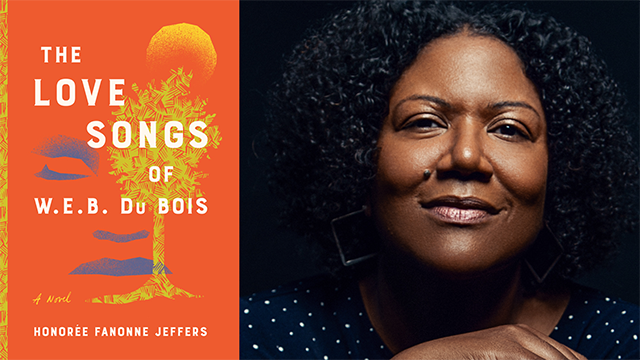

Honorée Fanonne Jeffers is a fiction writer, poet and essayist and the author of five poetry collections. Her first novel, The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois, is a magisterial epic, both intimate and sweeping, about one American family and the daughter who discovers its secrets—spanning from her ancestors who came from Africa on slave ships and who were indigenous to Georgia, through the Civil War, to our present, fractious day.

How do you view your role as a writer in this cultural and political moment?

I’m scared for this country, and I’m scared for the people I love who live here. However, I’m not an activist. I don’t hit the streets and I don’t make speeches. I’m just a writer and a deep thinker. While I begin writing only with the artistic questions and challenges that affect me—for all writers are selfish before they are generous—once I’m done with a poem or an essay or a scene in a story or novel, I look at it and hope that it will touch beauty in somebody.

I’m not sure that sparking beauty can change the world, but what I do know is that beauty can change how people think and that can change how they view the world—and all that might make people want to change their behavior for the better.

That point of view is not mine alone, but very much part of the tradition of African American writing in this country, going all the way back to the eighteenth century. Most Black writers always have been about trying to leave this country better than how we found it. Surely, there are some of us who are “artists first,” and who don’t think about culture and politics—and that’s completely okay, too.

What inspired you to write The Love Songs of W.E.B. Du Bois?

I can’t look back and say, “this is the moment that I decided to write this novel.” I can only piece together my memories at the time I began writing and hope for a cogent narrative.

What I know for certain is that the American south of my mother’s time, and also, the time of her ancestors has been a place that has occupied my imagination for almost three decades. That particular place—central Georgia—ached within me, and the people of that place have called to me. When I started writing my novel, that ache was very loud. I just wanted to soothe it.

That’s what I can explain. But then, there are dreams and spirit and prayer, which hovered over the novel when I was writing.

What is the core tenet of your book’s philosophy?

The main belief at the center of my novel is that Black history and Indigenous history is not marginalized—they are the center of this country, going back to the founding of this country, and the settling of the place we now call Georgia.

When anyone looks at Georgia, the only reason the English could have a place to live is because they violently stole the land from the Indigenous occupants. The only reason they could thrive is because they had Black people that they had brought over to this side of the Atlantic and violently forced those people to work. Every government building in Georgia constructed during the nineteenth century—every plantation house—was erected by unfree Black people and rests on land that used to belong to Indigenous peoples.

When we look at the pictures of white people—mostly cisgender men—in Georgia textbooks, those people were able to become so-called historical figures because of Black and Indigenous folks whose stories were erased. I did my best to imagine those peoples’ stories.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve received on writing fiction?

Though I didn’t know Toni Morrison personally, she used to say that whenever she began a new novel, there was a question that she wanted to answer. That’s what I do now. I figure, if it’s good enough for Toni Morrison, then it’s good enough for me!

What are you currently reading?

Right now, I’m reading Eric Foner’s masterpiece, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877. Lately, there has been talk about Reconstruction. Some people like the Reverend Dr. William J. Barber II are calling for a third Reconstruction because many scholars of American history say that the Civil Rights movement was the second one.

Since my work is about Georgia, its recent and distant history, and its implications for the broader American landscape, I’m really interested in what the original, post-Civil War Reconstruction did and didn’t accomplish. What are the historical lessons for progress and justice in our present moment? That’s what I’m thinking, as I read Eric Foner’s fabulous classic.