A simple experiment: what is the quality of the water coming out of your tap today? What do you know about the water that you and your family drink or bathe in every day? Chances are you have more information about the quality of the water in your can of soda or bottle of water than you do about the water in your home. The next experiment: try to use the internet to find out any information about your water. What is its quality? Where does it come from? Is there a shortage, or a surplus?

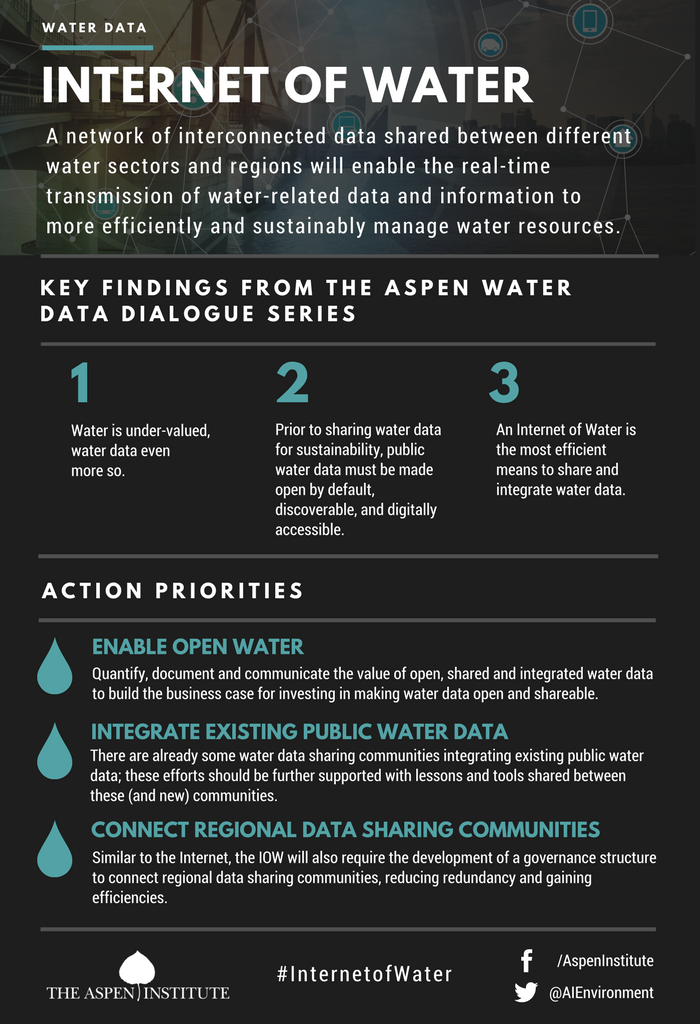

The problem is not a lack of data; it is a problem of putting that data to work. We live in a water world that is data rich, but information poor. Public agencies — from the federal government to state to local municipalities — collect tremendous amounts of data, but those data are used for narrow, specific purposes. Mostly the information appears in opaque forms or hard-to-access databases and then is ignored or forgotten.

Instead, if those same data were shared openly and then integrated in a common digital platform, there would be game-changing opportunities. Imagine using an integrated water website as part of house-hunting and getting information on groundwater trends in the area if the house relies on well water. Imagine if the house you’re reviewing is in the city or suburbs, seeing how many water quality violations the local water supplier had over the past five years. This integrated information could also be instrumental during a crisis, spreading to data sharing between farms and cities to flag the potential of an eminent toxic algal bloom, such as the 2014 bloom on Lake Erie which shut down water supply for half a million residents in Toledo.

At the annual Aspen-Nicholas Water Forum in May, the Aspen Institute released The Internet of Water. The work was based on a yearlong dialogue series that brought together some of the nation’s foremost thinkers on water management, big data and possibilities. The group envisioned an end goal — the Internet of Water — and a series of steps for reaching that goal.

The focal point is public, governmental water data: those data collected by public water agencies at all levels of government. Such data are collected at great cost and effort, but are largely unusable. Instead, those data need to be open, or ‘discoverable’ – in machine readable formats that allow someone to find them using standard internet platforms. From there, public water data need to be integrated so that data from different agencies, used for different purposes, are assimilated and allow the entire constellation of data to be available to many potential users.

This public data is really the platform — the scaffolding — for the Internet of Water around which many additional and different types of data can be organized. Think of this first public data step for the Internet of Water like Google Maps: all of those private apps and the tools to permit crowd-sourcing of traffic data and the subsequent uses for optimizing the placement of billboards and gas stations were possible only once the public road network had been digitized, made available broadly, and then integrated nationally, from the Interstate system to the smallest gravel road. From there, the technical and social power of the Internet took over, and most of us don’t leave the driveway without a navigation app telling us where to turn or a traffic app informing our choice of routes. In the same way, the Internet of Water depends on the vast stores of public, governmental water data being opened, shared, and integrated first; from there, the creativity, innovation and needs of broader society will take over — showing what types of applications and uses of water data are both needed and possible.

The other key recommendation from the Aspen Dialogue was that the Internet of Water should not be done through a central agency or organization. Instead they believed it should evolve in the same way that the internet itself did; through sharing and integrating data and allowing users to use the data for their own purposes, allowing the creativity of users to drive innovations that were previously unimaginable.

How to make this happen? The first pieces are starting to emerge: data hubs. These are communities that are opening and integrating data that are relevant to their needs. The Water Data Exchange, for instance, integrates water availability and use data in the arid west, providing critical information for irrigators and water suppliers. Similarly, the National Groundwater Monitoring Network integrates public groundwater data — both quantity and quality — that was previously dispersed between 19 different agencies; this simple integration is providing a nationwide view of aquifers available to citizens and scientists alike. Other water data hubs are also taking shape, from citizen science-based water data collections on specific rivers to an emerging hub for the Great Lakes.

What is needed next is the integration of these data hubs; this would be the Internet of Water — a backbone structure that aligns these growing but disparate data hubs into a hydro-data network. This Internet of Water would allow the hubs to continue developing their specific types of data, but integrate them into a more holistic and accurate view of water in the US.

With an Internet of Water integrating public water data, two big things are possible. First, private industry and entrepreneurs can do what they do best: innovate. Integrated water datasets will enable a water data revolution — whether startups, major software giants or teams of high school students are developing the apps. Tools to forecast water shortages, enable water market transactions, pinpoint leaky pipes, and spot municipal water quality issues like the crisis in Flint are more likely to emerge from disparate innovation when innovators are engaged with water data.

Second, an Internet of Water based on public data provides the platform for the burgeoning field of non-governmental data. Private individuals and companies will be able to quickly make use of the initial backbone of public data to provide context for their own private or proprietary data. In addition, integrated public data provides context for data generated by citizen scientists, or more likely in the future, crowd-sourced data. As the costs of water sensors decreases and the use of smart phones increases, everyday citizens are as likely to be sources of water data as agency scientists. What these citizen scientists need is a mechanism for sharing their data that quickly integrates with the broader view of water resources. For instance, we have little trouble believing backyard rainfall observations or observations of a traffic delay, because there are many others making simultaneous observations amidst a context of more rigorous, ‘official’ data: having a platform for those multiple water observations is a necessary precursor for crowd-sourced water data.

But these are the likely, obvious visions to us now; if we’ve learned anything from the Internet, it is that we are not likely to imagine how it will be used nor what people will find valuable and important. In the same way, it is more likely that the Internet of Water will enable innovations that are not imaginable now, hopefully toward a far more sustainable water future.

Martin Doyle and Lauren Patterson are both at Duke University’s Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions, which co-runs the annual Aspen-Nicholas Water Forum.