Technology, trade, and globalization continue to change the nature of work, making it less stable and secure. These trends impact the entire economy, but industries are affected at different rates. Retail is an industry that is experiencing major change, exposing its workforce to significant disruption.

Retail has long been an important industry for American workers – fifteen years ago it surpassed manufacturing as the country’s largest industry by employment.[1] Today, nearly 16 million people work in retail, accounting for more than one in ten workers. The industry includes companies like Walmart, the nation’s largest private sector employer (and the employer of 10% of retail workers), but also thousands of small businesses from restaurants to bowling alleys to gas stations. Retail workers include salespersons, cashiers, stock clerks, and first-line supervisors and managers. The median annual wages of these employees ranges from $20,160 for cashiers to $38,870 for first-line supervisors/managers. The retail workforce is slightly more female, African-American, and Hispanic than the overall workforce, and it is significantly younger.

Retail jobs can offer upward mobility for workers who have little post-secondary education or training. Over 80 percent of workers in the retail industry do not have college degrees, and over half lack any post-secondary education.[2] Researchers at the National Skills Coalition, a nonprofit organization that promotes investment in training, found that over 60 percent of workers in the service sector, which includes retail workers, have limited literacy skills, while nearly 75 percent have difficulty working with numbers.

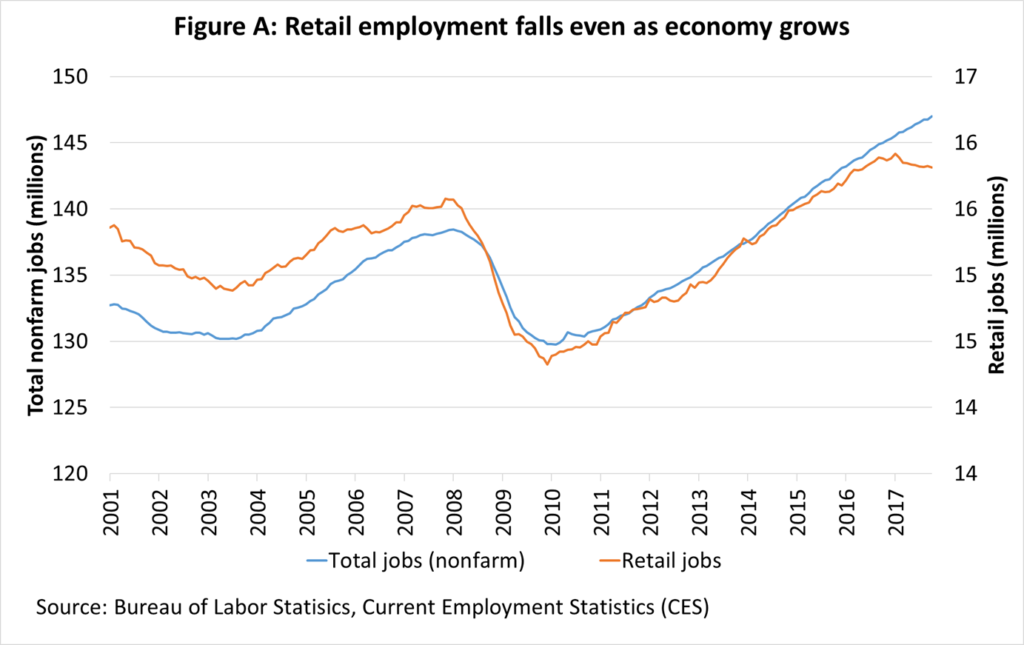

The retail industry may be on the verge of significant disruption. Because it is so heavily dependent on consumer spending, retail employment has traditionally tracked the overall state of the economy. Both retail and total employment fell from 2000 to 2002, rose from 2003 to mid-2007, fell again during the Great Recession, and then increased during the recovery (Figure A).

In 2017, however, the relationship between retail and overall employment diverged. Since January, the economy has gained nearly 1.5 million jobs, but the retail industry has lost 101,100 jobs.

More retail store closings have been announced this year than any other on record. Since January 1st, major retailers have announced plans to close 6,879 stores, a 224% increase over last year, surpassing the previous all-time high of 6,163 store closings in 2008. Radioshack alone announced 1,470 store closures in 2017.

Rise of E-Commerce

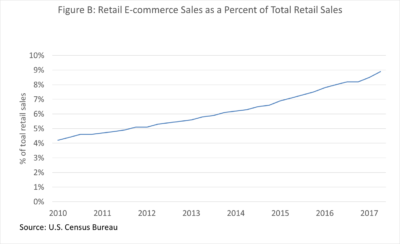

The number of retail store closings this year demonstrates the disruptive impact of the evolving shift from brick-and-mortar retail to e-commerce. According to the Census Bureau, since 2010, e-commerce retail sales have grown over four times faster than in-person sales (Figure B).

Accordingly, e-commerce sales as a share of total retail sales are growing significantly, doubling from 4.2 percent in 2010 to 8.9 percent today. JPMorgan Chase Institute’s Local Consumer Commerce Index shows that despite consistent overall growth in consumer spending, in-person purchases have stagnated since 2015. Goldman Sachs estimates that in-store sales require more than three and a half times as many workers as the same amount of sales transacted online.

At the same time, some companies are repurposing their existing facilities and workforce to improve their e-commerce services. This past summer, Walmart began testing associate delivery, which would allow the retailer to use its own facilities and workforce to deliver packages to nearby consumers. Similarly, IKEA recently purchased TaskRabbit to improve its delivery options. And while grocery stores have lagged behind others in the use of online shopping, Amazon’s purchase of Whole Foods suggests that this might change.

This trend shows no signs of abating. Technological advances in logistics (which, in the future, will likely feature drones), allow businesses to deliver goods faster and cheaper, suggesting that online retail will continue to gain market share at the expense of in-person retail shopping.

Growing Automation

Technology is increasingly capable of performing tasks previously done by workers, and retail jobs are particularly vulnerable. A typical retail salesperson engages in a range of work activities, many of which are susceptible to automation. While interacting with customers requires cognitive, social, and emotional capabilities that are difficult to automate, much of the job involves predictable, routine physical activities – such as ringing up sales and checking inventory – that existing technology can already perform. According to research by the McKinsey Global Institute, over half of all retail work activities could be automated using existing technologies.

Prominent retail companies are already shifting in this direction. Walmart used to rely on workers at individual stores to count cash and update stores’ books, but recently introduced machines to count cash – causing some employees to leave the company, while others were reassigned. Walmart has also begun experimenting with autonomous vehicles to clean their stores. And while self-checkout now can be found at most grocery stores, Amazon has experimented with convenience stores called “Amazon Go,” which use sensors to detect the items customers want to buy as they leave the store and then charge the cost to their Prime account.

McKinsey Global Institute estimates that a fully-automated retail store – in which facial recognition software, automated stocking shelves, augmented virtual reality, and checkout with sensors – would require two-thirds less labor hours than current stores, resulting in a significant loss of retail jobs.

The shift toward online purchasing and increased automation are important factors in this year’s overall decline in retail employment. However, Progressive Policy Institute economist Michael Mandel has noted that retail job losses may be overstated because traditional measures of retail employment do not appear to account for many of the new jobs that have been created in warehouses and fulfillment centers. He highlights that these jobs are often better-paying than traditional retail jobs.

But this job creation may be ephemeral. As jobs shift from stores – where interpersonal interactions are required – to fulfillment centers – where transportation, logistics and warehousing predominate – the work becomes far easier to automate. According to a report published by the Oxford Martin School and Citi, roughly 80 percent of such jobs are at risk of automation.

The changes in retail employment also have important geographic considerations. Retail job loss disproportionately impacts workers in rural communities because the new jobs created in fulfillment centers and warehouses are often located in suburbs. Similarly, newly created marketing and engineering jobs are generally clustered around larger cities. According to the New York Times, rural counties and small metropolitan areas account for about 23 percent of retail employment, but they are home to just 13 percent of e-commerce positions.

At this point, it is unclear how e-commerce and automation will affect different-sized retailers. On the one hand, large retailers may be the only ones able to make the investment in technology needed to remain competitive, disproportionately harming smaller stores. On the other hand, small, family- and worker-owned stores compete on more than just price. They provide a more intimate shopping experience, and many of their customers may appreciate their personalized customer service and adherence to inclusive, worker-friendly practices. Retail’s physical presence will not disappear, though it will certainly continue to change.

Industry-specific disruptions are particularly difficult problems for both the public and private sectors, but there are a number of constructive approaches that business and labor leaders are taking, and additional policy ideas that should be considered.

Historically, the retail industry has not focused on retraining workers. However, many large retailers are increasing their commitment to their workforce. In January 2017, the National Retail Federation gathered 21 retailers and nonprofit organizations to launch RISE Up (Retail Industry Skills & Education), a training and credentialing initiative designed to help entry-level workers achieve their broad professional goals.

Individual companies are also engaging in significant training efforts. For example, last year Walmart created the Walmart Academies, which provide both classroom learning and sales floor exercises to help retail workers develop the skills needed for their current, customer-facing positions, as well as those necessary for success in future professional endeavors. In the last two years, Walmart Academies have provided over 150,000 employees with two to six weeks of training.

Organized labor has also played an active role in supporting training programs for retail workers. The United Food and Commercial Workers International Union, which represents 1.3 million retail, grocery, and food processing workers, has established a system to help workers further their education to adjust to job displacement resulting from technological change.

Policymakers should consider modernizing our social insurance system to meet the needs of displaced workers. This modernization should focus on strengthening the unemployment insurance system, as well as expanding Trade Adjustment Assistance to workers disrupted by factors beyond international trade.

In addition, all workers – but particularly workers impacted by industry-wide disruptions – should be given ample opportunities to retrain for in-demand jobs. Policymakers should create worker-owned Lifelong Learning Accounts. These accounts, funded by contributions from individual workers, employers and government, could be used over the course of workers’ careers for training and education to broaden skills or transition to new jobs.

The retail industry, with its 16 million workers, is already experiencing significant disruption due to the shift toward e-commerce and increased automation. Government and businesses must work together to craft solutions, such as reforms to our social insurance system and employee training programs, in order to help workers adapt to the evolution of this industry.

[1] FRED data. Health care surpassed retail as the largest employer three years later.

[2] Author’s analysis of Current Population Survey data