As Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. once said, “We may have all come on different ships, but we’re in the same boat now.” Today, many reach the United States by other means, yet still face challenges to full participation in American life. While much progress has been made for African Americans since Dr. King uttered those words, many challenges remain. Though the civil rights battles of the 1960s are part of history now, the struggle for equality continues — not just for African Americans, but for the rapidly expanding Latino community as well.

Of course, the history of African enslavement set in motion an unparalleled series of obstacles to African Americans achieving equality. Yet many Latinos and other diverse groups have and continue to battle political disenfranchisement through redistricting, increased barriers to voting, and discrimination, all of which prevent them from fully realizing the American Dream.

The Aspen Institute Latinos & Society Program recently hosted a journalism tour in Charlotte, North Carolina, where rapid Latino migration has created a new entrepreneurialism, statewide economic benefits, and cultural vibrancy in many communities. These newcomers to the Southeast have sometimes faced a disturbing backlash that is representative of a larger national trend.

Large inflows of Latinos, mainly Mexicans and Central Americans, came to Charlotte when the city was booming before the Great Recession. In 1994, there were just 3,000 Latinos in Charlotte; now there are more than 125,000, representing 13 percent of Mecklenburg County’s population. Many came during a period of economic growth, recruited by contractors desperate for masons and other laborers to build the city center’s towering skyscrapers, as well as homes fueled by Charlotte’s financial services sector.

Newly arrived Latinos have varying legal statuses, even within individual families. We met American citizens with undocumented and legal resident parents and siblings. Individuals without legal status are particularly easy targets for discrimination by the state, and many of these families wait in limbo for national immigration reform.

Initially, many welcomed and praised these immigrants for their work ethic and skills, and overlooked their legal status. But since the 2007 financial crisis and subsequent economic turbulence, the tone has changed, particularly within the state government. Identification laws have been more aggressively enforced and deportations have increased, forcing many undocumented Latinos into a life without rights or protections. Charlotte officials continue their commitment to being a welcoming city for all, yet they must enforce state laws. Undocumented Latinos are unable to drive and denied the ability to receive basic forms of identification necessary for every day transactions; they are also ineligible for in-state college tuition, and face the constant specter of a relative being deported.

It is in this climate of social and economic exclusion that we found inspiring stories of undocumented Latino youth in Charlotte who, steeped in the history of the 1960s civil rights movement, have modeled their own struggle and tactics on those of African American predecessors.

Just as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee was a locus of civil rights activities in the 1960s, young undocumented students under the banner of United 4 The Dream have become a focal point of the Latino civil rights struggle. We met high-performing undocumented Latino students who participated in a march from Charlotte to Raleigh on foot to ask legislators for in-state tuition, since many could not afford to even attend the local community colleges.

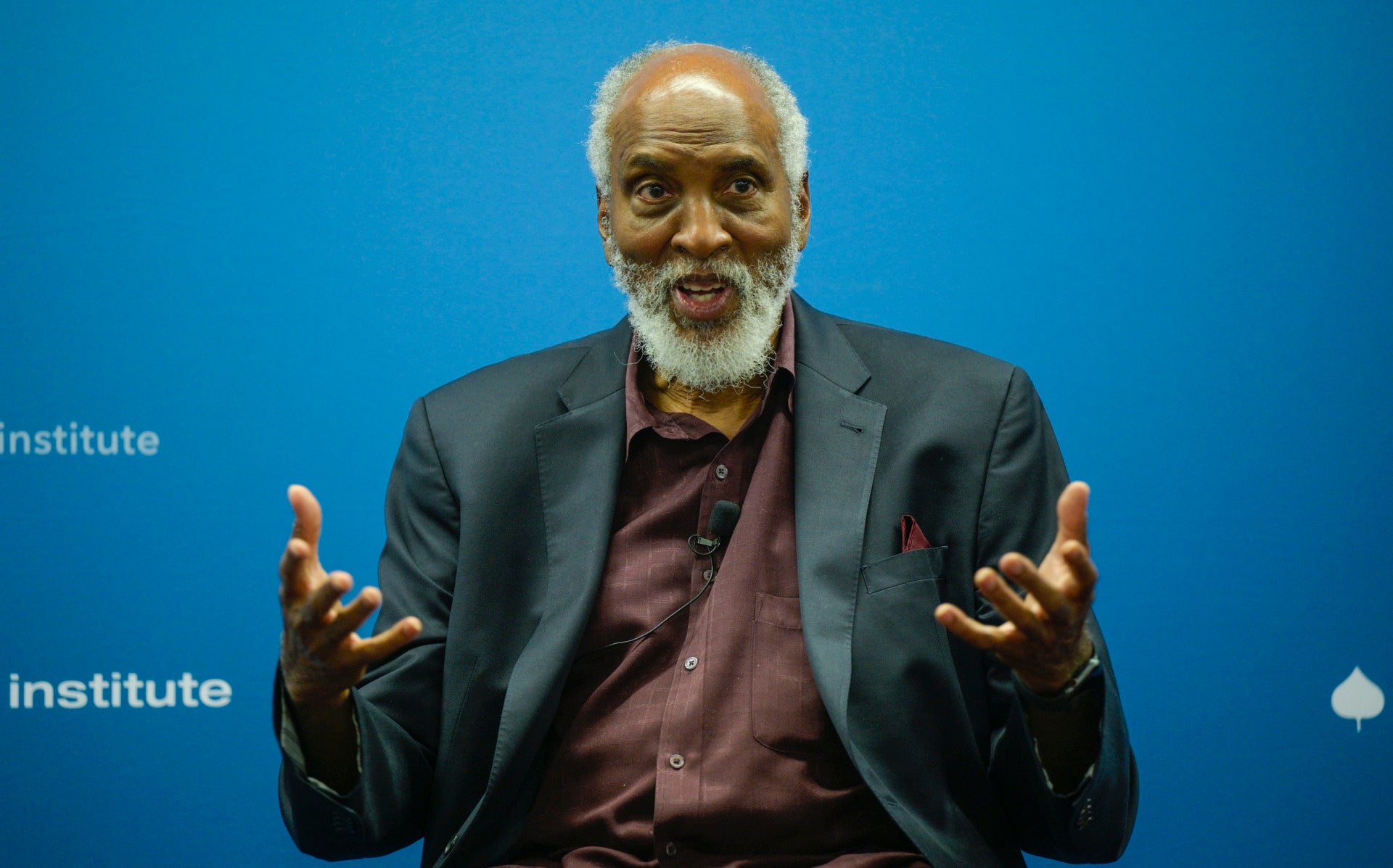

Rev. Dr. Rodney S. Sadler Jr., a leader of the Moral Monday protest movement, noted that the African American community relates to the plight of Latinos being stopped and deported as another example of “driving while brown.” Both African Americans and Latinos with citizenship have suffered a loss of political power due to state-sponsored efforts to limit voting rights— through preventing same-day registration, partisan redistricting, and a tough stance on the enforcement of showing voter IDs at the ballot box.

Historically, Latinos and African Americans have fought against state-sponsored discrimination separately, but rarely together. Patrick Graham, president and CEO of the Urban League of Central Carolinas, noted that Mendez vs. Westminster, a key anti-segregation case which challenged Mexican-only schools in California, helped pave the way for Brown vs. Board of Education. Though individual Latinos and African Americans recognize connections around a common plight and agenda, there is still much to be done toward moving from recognition to joint action.

The political power of groups battling discrimination can only be magnified through unity. The children of Charlotte’s undocumented workers have been raised as Americans, attended American schools and know the history of the civil rights movement in their communities. Regardless of their legal status, these young leaders represent a new generation of Americans who are ready to be a powerful force for equality in the South and add a new chapter to America’s struggle for civil rights. After all, these young leaders understand that we’re all in the same boat now.

Abigail Golden-Vazquez is a vice president and executive director of the Aspen Institute Latinos and Society Program. The opinions expressed in this piece are those of the author and may not necessarily represent the view of the Aspen Institute.