Photo by Mark Czajkowski

Aspen Words will confer the inaugural $35,000 Aspen Words Literary Prize this year, recognizing a work of fiction with social impact. Twenty nominees are still in the running, and the diverse list includes 12 novels and eight short story collections covering a variety of critical issues and published by an array of presses. While the juryworks on narrowing this list down to five finalists and a winner, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, the importance of fiction in understanding contemporary issues, and the books that have influenced them most.

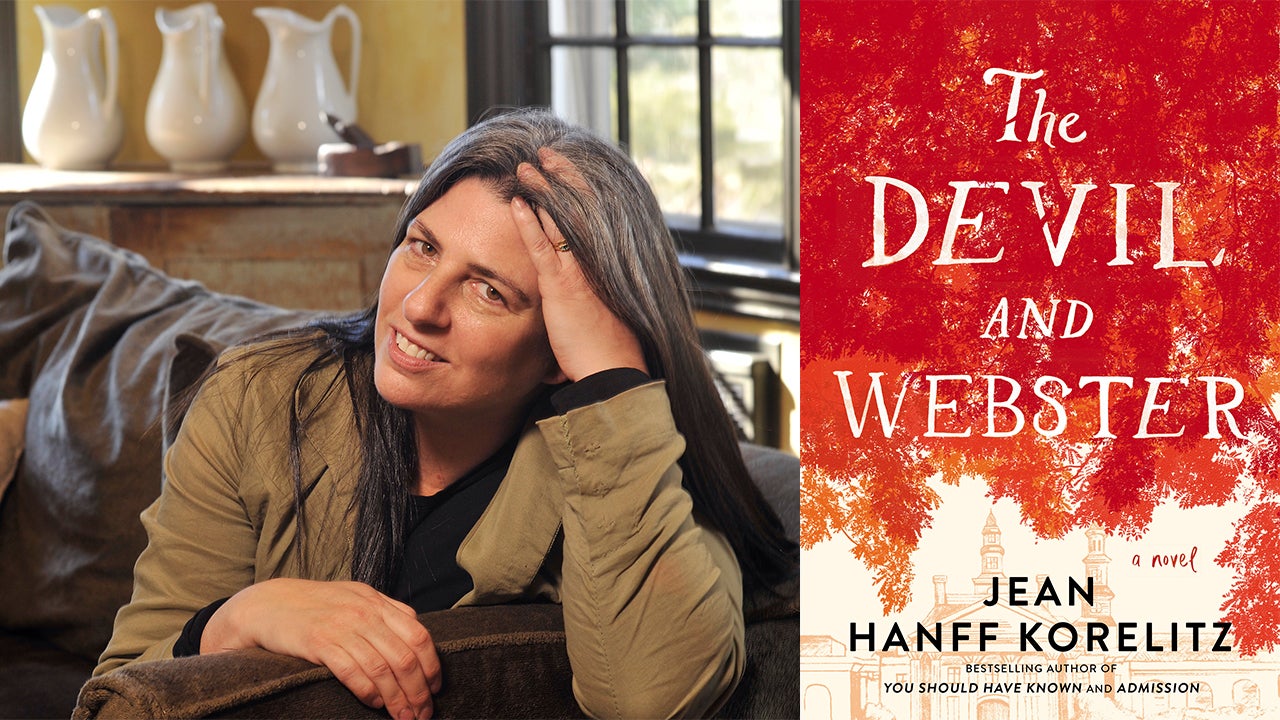

Jean Hanff Korelitz shines a spotlight on some of the most hot-button issues on today’s college campuses with her sixth novel The Devil and Webster. It follows Naomi Roth, an eastern liberal arts college’s first female president, as she grapples with the racial and sexual tensions bubbling up on campus. After students set up an Occupy-style camp in the center of the quad, Naomi – who was once a student activist and protestor herself – navigates the timeless conflicts of leadership, the estrangement of her daughter (a student at the college), and the hovering media presence as the crisis slips beyond her control.

Why did you write The Devil and Webster?

I am fascinated by the ways in which our opinions and political allegiances change as we age and move through the stages of our lives. If, as Robert Frost, once put it, “I never dared be radical when young for fear it would make me conservative when old,” what does happen to adults whose youthful activism once defined them? Although my own generation reached maturity two decades after the idealistic (sometimes destructively idealistic) young people of the Sixties, I’ve always been drawn to stories of how that generation course-corrected as they moved on into parenthood, responsibility, and the demands (and rewards) of work. Putting a former student activist into the very role she once considered a hated authority – that of college president – was too tempting to resist, and using that juxtaposition to explore some of the newer challenges on contemporary college campuses opened up so many stories, so many delicious possibilities.

What was the most challenging thing about writing this book?

The challenge is always to make a novel in which every sentence, every character and every part of the story converges to form something powerful, transformative, and beautiful. Admittedly, that’s a very tall order, but it’s always the hope, and while it’s true of few of the novels we’ll read in our lives, it can be said of those novels we love the most. In The Devil and Webster, I sometimes had to restrain my own tendency to veer towards satire, and sometimes my tender disapproval of my protagonist, Naomi Roth. She veers far from perfection, both in her professional and her personal lives, but she is a human being facing a serious adversary and some everyday challenges that are, in their way, just as daunting; as any parent will know, watching your child walk out the door and into her own life is not for the faint of heart.

How might fiction help us to explore contemporary issues?

I almost hesitate to say that fiction – which by definition is comprised of made-up things – gets us to a deeper truth than fact alone, because it seems so obvious to me. The “truth” of a Madame Bovary is so much deeper than even a detailed recitation of her story could ever be. The devastation of Gabriel Conroy, contemplating the snow in the final lines of James Joyce’s “The Dead,” is so much more tangible than a simple description of man standing at a window. I owe my own understanding of the world to the stories I’ve consumed, and the behavior of people in those stories, and I have always consumed fiction to learn how other people experience life, with the understanding that my reading mind is meeting the writing mind of the author – that’s where the connection gets made. Art, in all its forms, feeds us. Other people, of course, speak of music and performance the way I speak of fiction, and I understand exactly what they mean. But I happen to have a thing for language.

What was an early experience where you learned that language had power?

I remember the shapes of sentences and how they felt in my ears. I remember the power of a perfect story, which landed in precisely the right spot after rounding off every character, so that you were somehow reconciled to the fact that it was now over. When I first read Sylvia Plath’s famous essay, “Ocean 1212W,” and heard her description of that first encounter with poetry, I felt my own chill of recognition:

“I saw the gooseflesh on my skin. I did not know what made it. I was not cold. Had a ghost passed over? No, it was the poetry. A spark flew off (Matthew) Arnold and shook me, like a chill. I wanted to cry; I felt very odd. I had fallen into a new way of being happy.”

That “new way of being happy,” a perfect amalgam of the story and the words telling it – it’s what I open every book to find, and what I dream of making.

What book(s) have made you see the world differently? How?

For me, all roads lead to D’Aulaire’s Book of Greek Myths, the exquisite (yet encyclopedic!) collection of Hellenic legends, mythology, and history which I finished on a bench in Central Park when I was nine years old. Not only do these stories and characters continue to resonate in the world, they are as varied, insightful, ridiculous, tragic, haunting, and deeply satisfying as anything (indeed, everything) that has been written since. But there’s another reason D’Aulaire’s is the single most formative book I’ve ever read. By the time I turned the last page of the book on that park bench in 1970 I had become an atheist, utterly persuaded that these particular gods – and all gods – had been conjured by human inventiveness, and by our deep need for morality, justice, and order in the world. We’d made them, in other words, and not the other way around. Which, for the record, makes the gods of ancient Greece, and all of the gods that preceded and succeeded them, not one tiny bit less compelling.