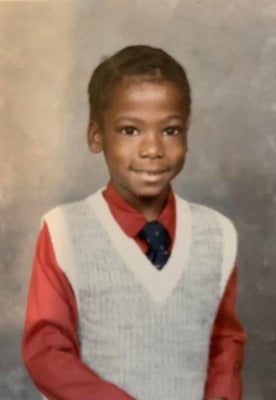

For as long as I can remember, Black History Month has been joyful. As a kid in Saginaw, Michigan, the month was filled with school plays and programs about great historical figures who challenged an unjust system, like Frederick Douglass, Rosa Parks, and Martin Luther King, Jr. I marveled at the obstacles they faced and the courage they showed.

Frederick Riley as a young boy

My family joined town celebrations honoring national and local heroes who had made lasting contributions to the world. I loved knowing people like me could be heroic. Yet I was secretly afraid—afraid that I didn’t have greatness in me. That I would end up just another Black man trying to navigate in a hostile world. And then I met Mrs. Sharon Floyd.

Mrs. Floyd was my high school English teacher. She carried herself with an air of grace and dignity and anyone who has ever taken her class knows she’s tougher than nails. I will forever remember, with a chill, her scolds and corrections. Proper English grammar did not come naturally to me. She knew I could be the first in my family to attend college and she never missed a chance to remind me of my weighty responsibility.

Yet with all her reprimands and strictness, her looks of disappointment, and her reminders that I had to fight for my place in the world, she also delivered love, kindness, and guidance. She led me through a foreign world of college tests and applications. And once I made it into college, I would call again and again, saying I needed advice on punctuation and grammar, but really needing to learn the grammar of that foreign culture.

She’d follow up each phone call with a letter enclosing some explanation of grammar to answer my questions, and always enclosed a check. She knew other students took college for granted, as an assumed rite of passage. She knew they had spending money. She knew my path was uncharted and it would be easy for me to get lost. And while I assumed I was her favorite, I later learned that she had treated many other kids like me in the same way.

My life has been blessed with people like Mrs. Floyd—examples of greatness so much closer to my life than the historical heroes we typically honor during Black History Month. As a small child, my pastor Reverend Roosevelt Austin was the most important person I had ever met. He made me feel important just by talking with me in his deep voice. I wanted to be like him when I grew up. I thought it was because of his skill sermonizing, his beautiful suits, wingtip shoes, and the Fleetwood Cadillac he drove.

Yet as I matured, I saw it was his kindness, love, and generosity that dazzled me. After he died this past summer, my mother divulged that over my childhood, he showed up for us in ways that I never knew. She indicated that he silently filled our dwindling food pantry, paid for boy scout uniforms, and even gave me spending money for a rare middle-school trip to London, warning her to tell no one of his help, because no one need carry the indignity of not being able to afford things. During his memorial, I found out he had done the same for many others.

These are the unsung Black heroes I’m now thinking about, honoring, and striving to copy. They don’t get Black History Month parades or statues or newspaper articles. Yet they fought the same injustices and prejudices of our society—not on a grand scale, but on a human scale. They showed the same love and strength, day in and day out, by serving one person at a time. They made it possible for me to be where I am.

Now, more than at any time in my life, I am surrounded by people like Mrs. Floyd and Rev. Austin. One year ago, I joined the Institute to lead Weave: The Social Fabric Project. At Weave, we see a deeply broken and increasingly lonely world, where people don’t trust, support, or find joy in each other. A world where suicide, violence, and drug addiction are rising, and where inequality is deepening. And we see the answer.

In every place we look, we find people who are quietly showing up for others, linking their success to that of their neighbors and friends, weaving a social fabric that welcomes and includes everyone. They are Black and white and brown, urban and rural, immigrant and citizen, conservative and liberal. We call them Weavers and our mission is to connect and support them. Our mission is to inspire new generations of Weavers to follow in their footsteps and to lift them as celebrated leaders. We believe Weavers are transforming their neighborhoods and will heal our broken nation—and ultimately the world.

Before now, I have never had a word to describe the network of people on whose shoulders I stand, but they are and should be remembered as Weavers. Their work, love, and generosity show up each day in the threads of my life, a well-worn quilt that is still in need of more stitches, but I am here because of them.

There is an old African Proverb that says, “I am because you are and, since you are, therefore I am.” I am keenly aware that I am because so many Weavers have come before me, touched my life, and helped me and others along this journey.

These are the heroes in my life that I remember this month. The beautiful thing is that they are not extraordinary, bigger-than-life figures credited with changing the course of history. They are the not-so-ordinary people who live among us, right now, and who are quietly changing the course of my life and yours. We can join them. We can all be heroes.

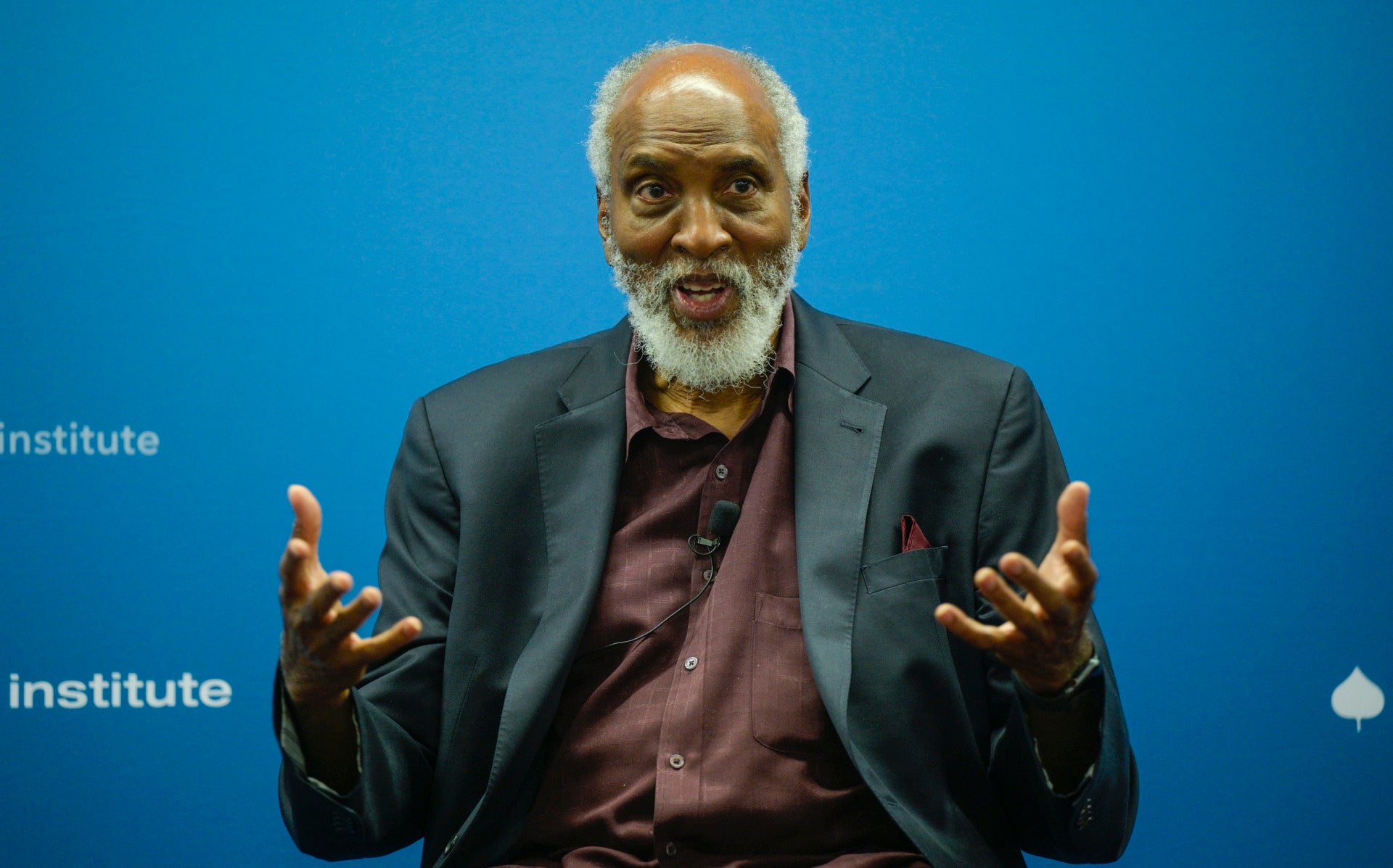

Frederick J. Riley is the executive director of the Institute’s Weave: The Social Fabric Project. Before Weave, he spent two decades working to ensure a positive life trajectory for youth, serving in local and national roles for the YMCA and the National Conference of Black Mayors.