On April 16, Aspen Words will confer the third annual Aspen Words Literary Prize, a $35,000 award recognizing a work of fiction that addresses a vital social issue. Sixteen nominees are still in the running, and the diverse list includes 12 novels and four short story collections covering a variety of critical issues and published by an array of presses. While the jury works on narrowing down this list to five finalists (to be announced February 19) and a winner, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, how they view their role as a writer in the cultural and political moment, and the best piece of writing advice they’ve received. You can find the series of conversations here.

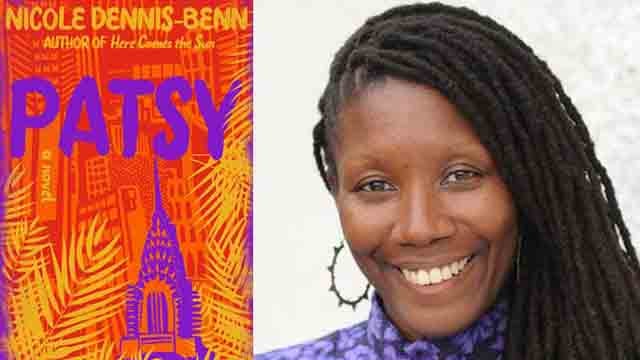

Nicole Dennis-Benn’s novel Patsy gives voice to a woman who looks to America for the opportunity to choose herself first, not to give a better life to her family back home. Dennis-Benn charts the geography of a hidden world—that of a paradise lost, swirling with the echoes of lilting patois—in which one woman fights to discover her sense of self in a world that tries to define her. Passionate, moving, and fiercely urgent, Patsy is a prismatic depiction of immigration and womanhood, and the lasting threads of love stretching across years and oceans. Dennis-Benn also is the author of the novel Here Comes the Sun.

How do you view your role as a writer in this cultural and political moment, and why is the time right for your book?

When I was writing Patsy, I did not know it would’ve been published during the current political and social climate. However, when I write, I often ask myself: What am I writing against? Usually, it’s ignorance. My goal as a writer is to challenge readers to transcend their own understanding of the world and empathize with others. I am really happy that Patsy hit the bookshelves at a time when this empathy is needed. I want people to empathize with what it’s like to not only be an undocumented black, queer, immigrant woman but a woman who has never desired the role of motherhood; a woman who had no choice in whether or not she wanted to be a mother; a working-class Jamaican woman who once claimed a homeland that never claimed her back; a woman who desperately wanted to find her place in the world and the chance to explore her own identity.

The conversation around immigration has always been fraught with a lack of knowledge. Very rarely do we see the human side of that want—that desperation, especially of a working-class black immigrant woman to exist in a country that is promised to the world as the land of the free, paved with gold. Similarly, the conversation around womanhood has always been fraught with the assumption that all women should innately desire motherhood and should be automatically good at it. My character, Patsy, dispels both of those myths. She came to America, not for altruistic reasons, but to seek personal freedom—something that is frowned upon when it’s a woman, a mother. She abandons her young daughter in Jamaica in a radical act of self-preservation. The book asks the question: What do we lose or gain when we choose ourselves, especially as women? At a time when women’s bodies are deemed as grounds for political debate and when undocumented immigrants are deemed as criminals, a book like Patsy adds to the discussion on all fronts, humanizing the individual faced with each dilemma.

What other author deserves this award and why?

All the books are excellent choices, tackling important themes that lend to necessary conversations. I’m really honored to be among the best of the best.

What is the core tenet of your book’s philosophy?

My book holds up a mirror for the reader to look at themselves and question ways in which they’ve contributed to the problem of alienating others.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

Writing is my second career. I studied Public Health and was a researcher for many years. I choose writing because it is the one thing that I’m wholly confident about doing, knowing that I have more of an impact on the world.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve received on writing fiction?

The best advice I had gotten about writing was from Nikki Giovanni. I was an MFA student in a crowded auditorium when she said, “If you’re absolutely terrified of a character or a story, then you’re doing something right. Keep at it.”