In March, Aspen Words announced the 2023 finalists for the sixth annual Aspen Words Literary Prize, a $35,000 award recognizing a work of fiction that addresses a vital social issue. The selected books explore the climate crisis, racism, xenophobia, and mental health, and feature a range of dynamic voices. While the jury works on selecting a winner, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, how they view their role as a writer in this cultural and political moment, and the best piece of writing advice they’ve received.

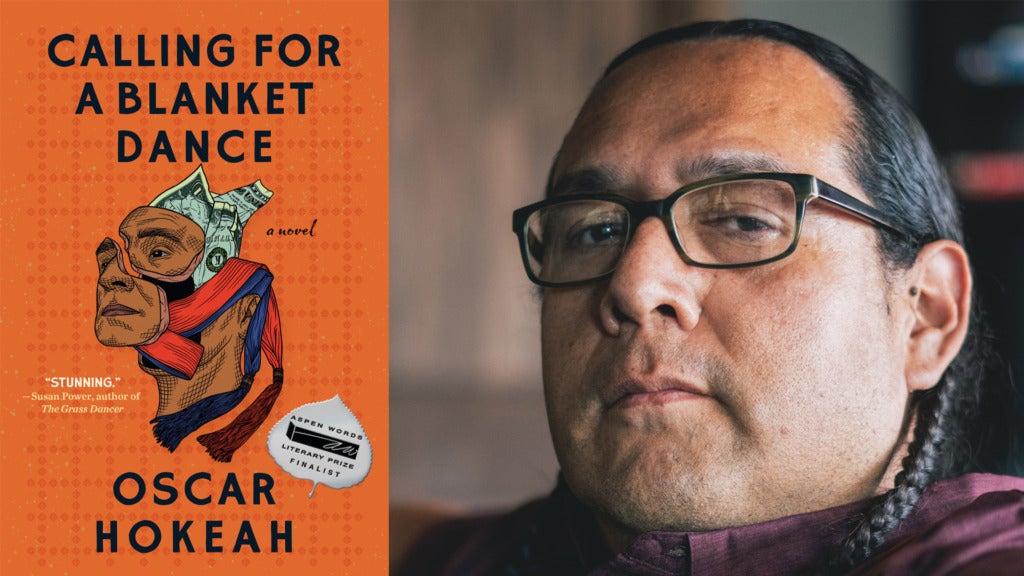

Oscar Hokeah is a citizen of Cherokee Nation and the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma from his mother’s side and has Latinx heritage through his father. He holds an MA in English with a concentration in Native American Literature from the University of Oklahoma, as well as a BFA in Creative Writing from the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA), with a minor in Indigenous Liberal Studies. He is a recipient of the Truman Capote Scholarship Award through IAIA and is also a winner of the Native Writer Award through the Taos Summer Writers Conference. His short stories have been published in South Dakota Review, American Short Fiction, Yellow Medicine Review, Surreal South, and Red Ink Magazine. He works with Indian Child Welfare in Tahlequah. Calling For a Blanket Dance is his first novel and is the winner of the PEN America/Hemingway Award for Debut Novel, and is a finalist for the L.A. Times Book Prize/Art Seidenbaum Award for First Fiction.

What about our current cultural and political moment inspired you to write Calling for a Blanket Dance?

There are two great themes I explore in my debut novel and there is a strong connection between them: intergenerational trauma and poverty. I often describe the main character, Ever Geimausaddle’s, experience as a decolonization narrative. For me as a Native artist, I think of decolonization work as healing work, as in healing intergenerational trauma. The means in which we Natives go about this process is often situated in our cultural practices and the strength of familial love. I’m impressed with Gabor Maté’s newest book, The Myth of Normal, where he writes, “Once we resolve to see clearly how things are, the process of healing—a word that, at its root, means “returning to wholeness”—can begin.” Ever is guided by a family who can see his trauma and serve to help return him to wholeness, as Maté points out. Ultimately, the act of true healing remains in Ever’s hands as we follow him into adulthood, where we bear witness to his transformation. Many of the obstacles in his path often derive from being born into poverty, where homelessness is only one tragedy away. My debut is an homage to the working poor, who aren’t trying to stratify a system, but simply want to keep their loved ones from becoming victims to a movable standard. Here I’d like to quote Gabor Maté again because he does a beautiful job of connecting the residual consequences of our current economic system on the modern psyche, where he pens, “A society that fails to value communality—our need to belong, to care for one another, and to feel caring energy flowing toward us—is a society facing away from the essence of what it means to be human.” Ever Geimausaddle navigates the pitfalls of being among the working poor—where dehumanization can result in violence, imprisonment, and early death—with the strength of familial love providing a far-reaching safety net.

Can you share an experience that taught you the power of language?

I moved away from my hometown in 2004 to live in Santa Fe, New Mexico. It wasn’t until I left Oklahoma that I truly appreciated the intertribal atmosphere I had grown up in. I was immediately intrigued with the New Mexican accent, and taken by the vibrant Native cultures of Pueblo, Apache, and Dine peoples. I would eventually marry into a Pueblo community and have two daughters who are half Pueblo. Hearing the richness of tribal accents and the intertwining of Indigenous languages with Spanish and English, I reflected deeply on my own upbring and realized I had grown up in a similar environment. Over the next 10 years, going back to visit family and then attending the University of Oklahoma for two years, I recognized the beauty of language in my own tribal communities, Kiowa and Cherokee. It took moving away to gain the insight I needed to appreciate what I had. Like many young people, I wanted to move away and do something unique and different with my life. The power of language for me is in the ever changing and ever evolving colloquial speech within hyper local communities. There is nothing more beautiful than new and unique vernacular being born out of the spirit of a collective. We have the autonomy to play with our words and develop compelling phrases, and most of all the blending of languages. In my debut, the main character is not only intertribal but he’s also biracial so he’s surrounded by the mixing of Kiowa, English, Cherokee, and Spanish. The result is the birth of a new original linguistic stock. One wrapped in the power of being true to one’s self while also honoring tribally specific collectives.

How did the process of writing this book change you?

My personal writing ideology is situated in catharsis. I write to better understand myself and the people around me. Because I’m so willing to be vulnerable on the page, I’ve been able to confront some of my greatest hardships, and in turn come to terms with the humanity of the family and friends closest to me. From imagining a relationship with my own grandfather through the character Vincent Geimausaddle to grappling with the emotions of losing a daughter, I was able to heal in profound ways, able to let go of the things I cannot control. I’m an advocate for literary fiction as a genre because of its call to action, which I view as not only it’s defense of social justice issues but also the artistry of exposing oneself for the benefit of society at large. When I sit down to write, I’m empowered by the permission to be authentically human. I feel if I can change while I write, then I give the reader the opportunity to change while they read. I write with tremendous emotion and want to reader to not only cry but to laugh and to be angry and frustrated and elated and hopeful, and sometimes all those things at once. Writing this novel allowed me to be better in touch with my own emotions. I hope it helps readers to do the same.

Which of the characters did you find most difficult to write?

Each had their own challenges, but one that surprised me was Ever’s father, Everardo Francisco Carrillo-Chavez. He was modeled off my own father, Oscar Francisco Carrillo-Chavez. It was difficult because my father was abusive, like the character in the novel. I had to come to terms with his abuse and how it had an effect on me and my life. The only way I could do this was through the lens of peripheral narration. Good writing requires us to capture all sides of a character. Portraying Everardo as a villain just wasn’t going to work. Since he was modeled off my own father, I had start looking at Everardo from the eyes of the people who loved him the most, like his niece, Araceli Chavez. Then I could see how charming and funny he was, and it reminded me of how charming and funny my own father was. Everardo doesn’t show up very often in the novel. He mostly makes appearances at the beginning, and then he’s referenced at later points. But because I had to search for his humanity, and ultimately the humanity in my own father, Everardo was a much-needed challenge. And I’m a better person, and a better writer, for it.

Some say writers should write the book they need to read. Why did you need this book, and what do you hope it says to others?

In the back of my mind I’m always thinking of my tribal communities. I do write to process, like I mentioned above, but I feel like there are harsh truths that we need to face as Native people—especially as we seek to heal intergenerational trauma. We depend on our artists to capture those truths for us. It gives us opportunity to reflect, find answers, and begin the healing process. In addition, I’m always looking for reflections of my own personal experiences as a means of validation. When I was a teen and young adult, I didn’t find literature capturing the Mex-Indigenous experience. I was validated when I crossed Robert J. Conley’s writing on Cherokee communities and histories. Likewise, I was validated when I read N. Scott Momaday’s book The Way to Rainy Mountain with its Kiowa specific narrative. What was missing for me was a narrative that showcased the intermarrying of Spanish and Native peoples. I found old western novels that depicted this exchange in historical fiction, but I didn’t have anything contemporary. For a young person, it’s important to see themselves reflected in art. The Mex-Indigenous experience is a major part of the American experience. So to a certain extent I wrote this novel for all those Mexican-Indian kids out there, looking to see themselves in storylines somewhere, quietly seeking validation.

What was the last book you couldn’t put down?

It might seem odd for me to say this, but Alice Munro’s writing captivates me. Here she’s a white lady from Canada, and I’m a Native guy from Oklahoma. It seems an unlikely pairing. Her craft amazes me. The worlds she creates are so true to the human condition. My favorite is her book Too Much Happiness. I often go back to her short story, Child’s Play, and fall into the storyline, the musical way she tells a story. I feel the rhythms of her language and get swept away by the audacity of her characters. Her world feels both familiar and foreign. It’s an odd feeling, but one I’m always excited to engage with again and again. In addition, I still sit and think of Louise Erdrich’s novel, The Round House. I remember it vividly and I probably haven’t read it in a couple years now. My first reading was back in 2012, but I’ve read it several times since. There was something compelling about the protective nature of the main character and his desire to do right by his mother. It spoke to me, and I remember being completely gripped by it. This was one of those novels that made me fall in love with literature all over again. There are certain books I read over and over, and The Round House is one of them.