The early days of the COVID-19 pandemic seemed to portend a re-appraisal of the value of work. People around the world took to apartment balconies and front porches to cheer for frontline workers. Retail companies announced special bonuses for employees keeping shelves stocked. More than a year later, have these changes contributed to lasting transformations in thinking from boardrooms to business schools?

To explore this question, we spoke with Arizona State University’s Elizabeth Castillo, winner of an Ideas Worth Teaching Award for her course, Resource Allocation in Organizations. Castillo’s course challenges fundamental assumptions about what can and cannot be measured in business—and where the real drivers of value creation lie.

![]()

Your course questions the assumption that financial capital is the primary engine of value creation. In light of the upcoming Labor Day holiday in the US, how has the pandemic reshaped the valuation of human capital—particularly front-line workers? How is this reflected (or not) in typical economic metrics like stock prices or labor shortages?

The pandemic was a tipping point for several longstanding human capital problems, including high staff turnover among front-line workers; low levels of employee engagement; gender and racial disparities in the workplace; family caretaking responsibilities and work-life balance; and insufficient living wages to support a family, fueling social polarization and growing inequality. These issues caused people to reevaluate their relationship to the workplace. Many have switched occupations or pursued self-employment to overcome the economic insecurity of the labor market. The result is that businesses now face a severe worker shortage.

However, one positive has emerged: a growing recognition that human capital is vital to firm success and innovation. Typical economic metrics, such as GDP and stock prices, don’t capture human capital contributions. They either view labor as an expense instead of an asset, or as a logistical problem rather than an issue that materially affects the future value creation potential of a firm. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) recognizes this gap and is working to rectify it. It recently introduced new disclosure requirements for human capital that call for firms to provide investors and other stakeholders with information such as worker safety records; compensation and benefits policies; employee engagement and professional development statistics; diversity, equity, and inclusion measures; and human capital management processes. These disclosures are an important first step to reshape how human capital is appreciated and valued.

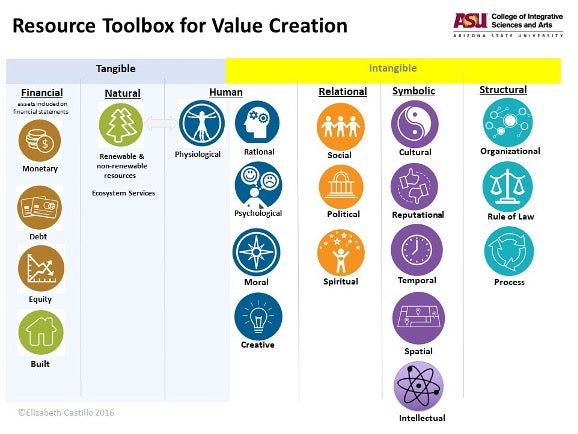

What is a resource, and why is it important for students to incorporate intangible factors like relationships, knowledge, and legitimacy into conceptions of value creation and profitability? And what is ultimately at stake if managers and leaders do not consider such intangible assets in strategy and resource allocation decisions?

A resource is anything we value that helps us to achieve a goal. Resources can be tangible (things that have a physical form or that can be quantitatively valued), or intangible (a non-monetary asset without physical substance). It’s urgent for students and managers to understand and account for intangible factors because in today’s digital knowledge economy, up to 90% of a company’s value stems from non-financial resources, including intellectual capital, human capital, corporate culture and ethics, reputational capital, nature (natural capital), governance and rule of law, and relationships (social capital).

Collectively, these financial and non-financial resources function as inputs into a company’s business model, making explicit whether a firm creates value for—or extracts value from—society. The benefits or harms a company produces either enhance or erode its legitimacy and social license to operate. Illuminating non-financial resources in a company’s business model is also essential to prevent underinvestment in them.

Social accounting also provides a way for companies to account for their values and stop confusing profit as an end unto itself, instead recognizing it as a means to increase cooperative surplus and inclusive prosperity. Ultimately, what is at stake if leaders fail to consider these matters is the very viability of our economy and communities. The crises we now face—environmental degradation, climate change, inequality, social polarization—reflect companies’ historic disregard for things that don’t show up on a balance sheet. Social accounting reorients the economy to what is truly valuable so that people, organizations, and societies can thrive.

This course teaches undergrads how to read a balance sheet but also tackles such heady concepts as the rule of law. What is your pedagogical intent in building this wide range of topics into an undergraduate course?

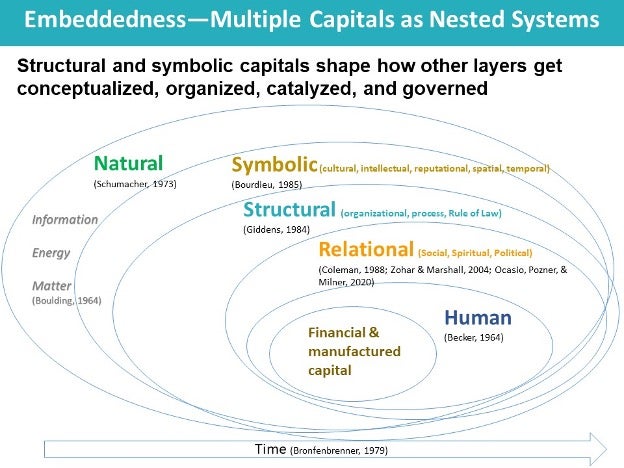

The intent of the course’s interdisciplinary approach is to provide students with a more expansive resource toolbox to create the world they want. A first step is to get clear about their values and how these function as reliable guides for wise decision making, planning, action, and reflection. Social accounting provides a framework to align values, goals, behaviors, and metrics. It also functions as a strategic planning tool to recognize, develop, and integrate the many resources that go into sustainable business models, such as human, social, natural, political, and cultural capitals. These multiple capitals make visible the nested systems that make sustainable value creation possible and how these interact to shape economic and social life, for better or worse.

The course also helps students to think about their thinking, such as surfacing implicit assumptions and identifying competing values and tradeoffs in resource allocation decisions. For example, how we conceptualize what counts as a resource greatly influences what goals we pursue (e.g., profit maximization, quality of life, sustainability). It also constrains or expands our perception of what is possible. Looking at the world primarily through market logic generally leads to underinvestment in things that make for a good life and society, like health, knowledge, relationships, and community. Viewing resource allocation through an interdisciplinary, multi-level lens (e.g., individual, organization, community, planetary) helps managers understand how various ingredients work synergistically to generate quality of life, successful organizations, and a vibrant civil society.

As alumni from your course go into leadership positions across industries and sectors, what is the one lesson that you hope will stick with them throughout their careers?

I hope leaders consistently think about their values and use them intentionally to guide their goals, decisions, and actions. Remembering the deep interdependence between people, nature, politics, belief systems, and the economy will enable managers to exercise prosocial leadership to shape a better world for current and future generations.

![]()

Interested in more innovative insights for business education? Browse our complete collection of interviews with outstanding educators, and subscribe to our weekly Ideas Worth Teaching digest!