Whether the result of overtly racist attitudes or subconscious bias that predisposes some to assume the worst when encountering young African-American men, it is clear by now that race is a factor in the frequency with which interactions between law enforcement and blacks too often end up violently and with unarmed black men dead in the streets. This is a serious matter and deserving of the urgent attention it is now, far too late, receiving. But there is more here than violence between black and white, and the racial dimension of the problem has overshadowed at least two other serious concerns.

A personal note: I have twice been the victim of a criminal attack. A little more than a week ago, I was attacked, beaten, and robbed by a mugger in a city park in New Orleans, in broad daylight, when I went for a morning walk while directing an Aspen Institute seminar. In that instance, the criminal was black. Years before, when I was a college student in Oklahoma, I was confronted by three armed men who attempted to rob me and in the process shot me three times (I still have bullet fragments in my chest). All three of those men were white. In my own experience, of those criminals who have attacked me, one-fourth was black; three-fourths were white. Just saying.

Leaving aside what is in dispute — for example, did Michael Brown attack the police officer who accosted him — there remains the fact that, regardless of how the confrontation ended, it was a confrontation that should never have taken place. The fact is, there has developed a disturbing pattern of abusive behavior — bullying, by one means or another — among a variety of elements in the law enforcement community. I have enormous regard for the men and women who put their lives on the line to protect us against predators and I have equally high regard for those who in other ways assume positions of authority designed to ensure that we live in a just society. But there are altogether too many examples of bad apples in those otherwise beneficial barrels.

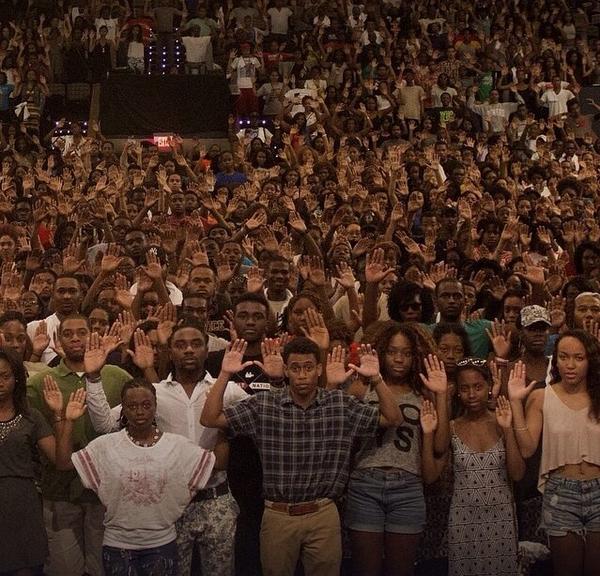

Advocates for citizen rights noted that police officers who were not involved in the Michael Brown shooting routinely attempted to force angry but peaceful protesters to disperse as though constitutional guarantees of the right to assemble did not exist. Police seize phones and cameras recording their interactions with private citizens. Civil liberties activists have noted with increasing concern instances of prosecutorial abuse — state and federal attorneys turning into Javert-like zealots who too often withhold evidence in their passion to punish. IRS officials have been accused — with some evidence — of using their offices to hinder the activities of those who hold political views they find offensive.

There is a term used in the law enforcement community — “badge heavy” — to describe those who become carried away by the sense of power that has been bestowed upon them. Make no mistake, it is a minority; most men and women in public service and law enforcement do good work and do it properly; still, there is a “badge-heavy” element, people who bully because they can, and that is a problem that transcends questions of skin color.

Finally, one more problem needs to be addressed. Michael Brown is dead today as the result of a confrontation that began because he was walking in the street. Eric Garner is dead today as the result of a confrontation that began because he was selling individual cigarettes. A New York Times story noted one young African-American man who was shot and killed because he was running across a roof top because it was the fastest way to get to his destination. Walking in the street; selling cigarettes; running across a rooftop. Each of these things ended in a death sentence. This is a matter of black and white but it is not just that; it is a matter of law gone crazy, of making too many things a crime. It is criminalization run amok. And that is a fault not of the police or prosecutors or IRS officials; it is the fault of lawmakers — city, state, and federal — who are far better at proscription than prescription. Restraint is sometimes a good thing: perhaps more of those who “serve” us should practice it.

Mickey Edwards is vice president of the Aspen Institute and serves as director of the Aspen Institute Rodel Fellowships in Public Leadership. He was a Republican member of Congress from Oklahoma from 1977 to 1992.