In November 2015, an African American civil rights group at Princeton University called the Black Justice League sent a LETTER OF DEMANDS to the administration that called for, among other things, cultural competency training for staff and faculty and a dedicated cultural space specifically for Black students. The letter made national headlines for its section about a particular former president: “We demand the university administration publicly acknowledge the racist legacy of Woodrow Wilson… We also demand that steps be made to rename Wilson residential college, the Woodrow Wilson School of Public Policy and International affairs… We would like the mural of Wilson be removed from the Wilcox dining hall.” After sending the letter, the students staged a 32-hour sit-in in the office of President Christopher Eisgruber, after which Eisgruber agreed to consider and execute some of the BJL’s demands. As of now, neither Wilson’s name nor the mural have been removed. Madeleine Le Cesne, currently a Princeton freshman, has the inside view on life at the school in the intervening months.

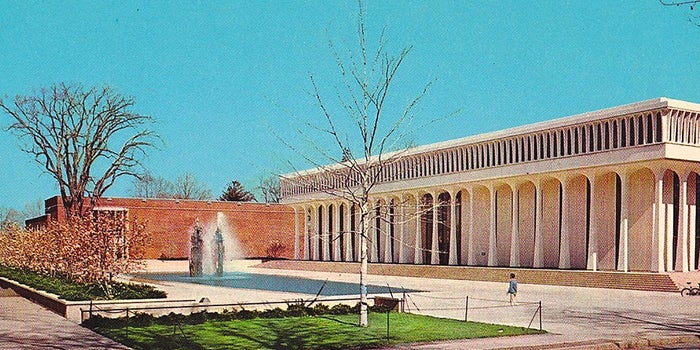

Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs, Princeton University

Driving from Princeton to D.C. for Thanksgiving, a friend’s mother asks how school is going and the conversation inevitably slips into the question of the name change. My three friends and I eventually all agree that no, it’s not a good idea. Even great minority figures participated in prejudice. We have the evidence to support it: Martin Luther King Jr. advised a young gay man that it was necessary to “deal with [this] problem,”; referring to Black Africans by the derogatory term “Kaffirs,” Mahatma Gandhi said that their “sole ambition” was to spend their lives in “indolence and nakedness”; on returning from a trip to Germany, W. E. B. Du Bois wrote that the Nazi hatred of Jewish people was a “reasoned prejudice, or economic fear.” No one is good enough to escape their time; one cannot know what is not taught. And like so many others, we don’t really understand what the Black Justice League is asking us to see.

My friend Esther comes to my room and we talk about the protests. She says she doesn’t feel like she has a place to talk about these things since she is a white Jewish female. “It’s sad,” we both sigh. But I don’t say, “I want to know what you think. Tell me. It’s okay.”

Overheard: “You can’t say anything on this campus these days.”

Conversation in the dining hall: a boy insists that even most black students are against the demands and behavior of the Black Justice League. He says he has the data to prove it. I disagree, voice beginning to rise, and turn to the only other black person at the table for support, asking him to “black me up.” Any tension we had been building evaporates with my slip of the tongue, and everyone laughs so hard we never finish the conversation.

Talking to a Chinese-American boy on my floor, I’m only half-listening because it’s late and the room is cold. He tells me how Eurocentric it is to place all the blame of racism on white people. I yawn and agree, but he keeps hammering at the point, misreading my disinterest for dissent, until I dismiss myself for bed. I can tell this upsets him, but who would have stayed for confirmation of more fears?

Esther takes me to a talk at the Center for Jewish Life about the Israeli occupation. After, we walk to dinner and she asks me what I think of it all, the presentation and the situation. I tell her I feel like I don’t have the place to say. We cannot wean ourselves off this answer.

I go by myself to an open discussion on race and the arts hosted by the Lewis Center. During the talk, a BJL organizer says, “We have been hurt,” and I understand that she means it happened here.

I walk to the CVS in town because there isn’t anywhere on campus that carries the products I use in my hair. It is the coldest night here so far. As I return to campus, rain begins and traffic slows down in the night. I walk through the FitzRandolph Gate and avoid the tent pitched outside Nassau Hall for students to sit in solidarity with those sitting-in at President Eisgruber’s office. The wind blows the tent so forcefully that I realize nobody is in it. A few feet away, a small parade of students is marching and chanting, “We out here. We been here. We ain’t leaving. We are loved,”—which originated with the protests at Yale this past October. This part of campus sits empty. Even the streetlights seem dimmed. There are too few students in the procession for their voices to carry beyond this spot. The wind swallows their song. Unless you are standing here, it’s just another night that’s colder than the rest.

It’s January, and I mention to a friend that I’m thinking of joining the Black Student Union once the spring semester begins in February. He says the protests have given the Black Student Union a “bad reputation,” forgetting that it was the BJL, not the Black Student Union that organized the protests. He doesn’t realize he’s slipped, and his opinion is shared by many here: black leadership organizations have a “bad reputation.”

The first time I felt at home here: I walked to the dining hall and found one of the BJL’s posters—a photo of Woodrow Wilson overlaid with his own words, ““The whole temper and tradition of the place [Princeton] are such that no Negro has ever applied for admission, and it seems unlikely that the question will ever assume practical form.” This gave me the assurance that I could be myself at Princeton, since a group of students had shared openly what I had been feeling: alienation. The Black Justice League remains the bravest thing I’ve seen here.

The Black Justice League is the first group to publicly demand accountability from The Woodrow Wilson School to live up to its unofficial motto, “Princeton in the Nation’s Service and in the Service of All Nations.” They are not asking us to revise history, to forget Wilson’s great achievements. Rather, they demand of us to consider what progress really is, how a person’s love can serve one people and not another.

On the phone at work the day the Wilson name change made national news, an alumnus tells me he won’t be making a gift to the university until we “sort this mess out,” only then will he continue his support. After this refusal, we talk about my classes and the weather, how I’m so lucky to be in a dorm with AC, and what a wonderful place this is. We both mean it.