On April 16, Aspen Words will confer the third annual Aspen Words Literary Prize, a $35,000 award recognizing a work of fiction that addresses a vital social issue. Sixteen nominees are still in the running, and the diverse list includes 12 novels and four short story collections covering a variety of critical issues and published by an array of presses. While the jury works on narrowing down this list to five finalists (to be announced February 19) and a winner, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, how they view their role as a writer in the cultural and political moment, and the best piece of writing advice they’ve received. You can find the series of conversations here.

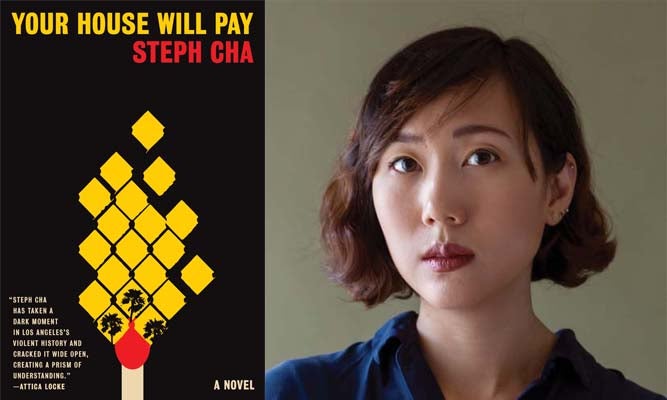

Steph Cha uses the tragic 1991 death of Latasha Harlins — the aftermath of which helped start the unrest in Los Angeles that led to the Rodney King riots — as inspiration for her novel Your House Will Pay. Set in the present day, it explores the relationship between an African-American family and a Korean-American family as they navigate the legacy of a decades-old crime to illustrate larger issues of racial injustice, generational violence, and social unrest. With massive civil protests, criminal justice reform, and diverse representation in the headlines daily, Your House Will Pay is timely, urgent, and quite moving.

How do you view your role as a writer in this cultural and political moment, and why is the time right for your book?

I write about collision and struggle in Greater Los Angeles, home to more than one in eighteen people living in America. Most of the country’s problems play out in L.A., where people from every cultural background work to find a foothold — in the American dream or just a life of dignity for themselves and their families. My book deals with a clash between two of these families, one black and one Korean, dating from 1991, one year before the L.A. Uprising, to present day. It looks at a common type of racial tension that strikes me as underexplored in media, not between black and white Americans, but between immigrant and non-immigrant minority groups, who are often pitted against each other because of the framework of white supremacy.

I honestly think a book like mine was a long time coming. It’s been almost three decades since the L.A. Uprising, and there haven’t been many other novels that excavate the tension between the black and Korean communities in Los Angeles (I haven’t found another, actually, and I have looked). But Your House Will Pay isn’t about the early ’90s. It’s a contemporary novel that ties the turmoil of that period to the issues of the present — police violence, anti-blackness, civil unrest, and activism in the age of social media. I also don’t think the issues are entirely specific to Southern California. Wherever there’s white divestment, recent immigrants and black Americans end up thrown together in a way that often breeds resentment and conflict.

I come from a crime fiction background, and I write about the social dimension of crime in a time when the country is absolutely riddled with violence and malfeasance of every variety. You learn so much about a place by looking at who hurts who and why.

What other author deserves this award and why?

I haven’t yet read all the other longlisted authors (I’m working on it!), but I love The Other Americans by Laila Lalami. It’s a rich, empathetic novel that examines the lives of a diverse group of Americans in the aftermath of a crime. Lalami writes thoughtfully about family and immigration, loyalty and hostility — all the ties and fractures that define a desert community in Southern California.

What is the core tenet of your book’s philosophy?

The personal is political and the political is personal. To pretend otherwise is a choice and a choice that isn’t available to everyone. At its core, my book is about two people who try very hard — one from ignorance and laziness, the other from exhaustion — to stay in their own worlds and mind their own business, but are forced into the political fray by events outside of their control. Politics don’t always ram through the door of your family home, but they often barge in uninvited, and they certainly infiltrate all of our lives in at least subtle, invisible ways.

If you weren’t a writer, what would you be?

I have a law degree and am technically a lawyer in good standing with the California bar, so I guess I’d be a lawyer. I went to law school because of a vague, still-developing interest in social justice that eventually turned me into a novelist. I suppose I could also have followed that interest into the actual practice of law.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve received on writing fiction?

I didn’t know any writers growing up and didn’t pursue an MFA (I fully did not know you could go to graduate school for creative writing until I was halfway through law school), so pretty much right up until I finished my first manuscript, I thought of writing novels as a sort of magical endeavor instead of a craft you could hone by just putting in the work. The best piece of advice I’ve gotten is probably some variation on “Sit down and force yourself to write, and also writer’s block isn’t a thing.”