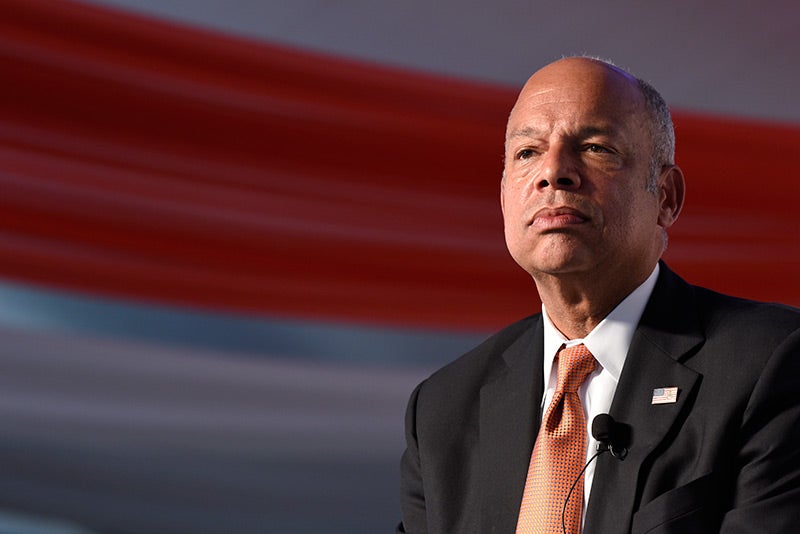

(Photo Credit: Daniel Bayer/The Aspen Institute)

Homeland Security Secretary Jeh Johnson, former white shoe firm lawyer and Defense Department general counsel, is a soft-spoken, even kindly man. Yet he commands the third largest agency in the U.S. government, a post-9/11 conglomeration of the non-military agencies — from counter-terrorism to cyber security to the Transportation Security Administration — trying to protect America within its borders.

On Wednesday night, before hundreds under a tent at the Aspen Security Forum conference, this man who is averse to hyperbole himself took aim at the rhetoric of a man who revels in it, Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump.

Johnson’s message, in so many words, was that Trump’s anti-Muslim rhetoric posed a national security risk to the United States.

He never said it that bluntly, of course. That’s not Johnson’s way. And he never mentioned Trump by name, despite being pressed to do so. But his charge was a serious one. Calls to ban Muslim immigrants or monitor those already in the U.S. (as Trump has done) undermines a crucial American counter-terrorism tool, he said– to get American Muslims to identify their fellow Muslims they see sliding into self-radicalization.

“Rhetoric that vilifies American Muslims is counter to our efforts, Johnson said. “It’s a setback to our Homeland Security efforts.”

Enlisting American Muslims in this campaign has become much more important in the last two years as the Islamic State — responding to military pressure in Iraq and Syria — calls on sympathizers to attack Westerners where they live. “Clearly that is their No. 1 priority,” Johnson said. “It’s low-cost, low-risk,” and a lot easier than sneaking trained operatives into the U.S.

Johnson agreed with Trump in one regard. In analyzing the run-ups to the San Bernardino, Orlando or other attacks, said Johnson, “it’s almost always the case that when someone self-radicalizes, someone has noticed something.”

But his view on how to use that information is very different. Trump’s answer is to surveil American mosques and predominantly Muslim neighborhoods. Johnson, who meets often with Muslim-American communities and leaders all over the country, takes the opposite approach: to work with them.

One obstacle to that is distrust. That distrust has roots in the immediate post-9/11 days, when Muslims were indeed singled out and targeted. But Johnson said that even today, “overheated rhetoric that fans fears and conflicts has consequences.” He has experienced those consequences in the wariness that greets him and his deputies in initial meetings with Muslim community groups.

And what of the debate over whether to attribute these attacks to “radical Islam” as Trump insists, but President Obama declines to do? Again, Johnson wouldn’t take partisan sides. But he said Muslims constantly tell him “ISIL has hijacked my religion. So when you call them ‘Islamic extremists,’ that’s a problem for us.”

If we employ such rhetoric, Johnson said, “we are not going to get very far.” A sobering assessment from a man trying to develop a crucial tool in America’s counter-terrorism arsenal.

Margaret Warner is chief Foreign Correspondent for PBS NewsHour.

This piece originally appeared on the PBS NewsHour website.