On February 17, Aspen Words will announce the shortlist for the fourth annual Aspen Words Literary Prize, a $35,000 award recognizing a work of fiction that addresses a vital social issue. Fifteen works are still in the running, and the diverse list includes 13 novels and two short story collections. While the jury works on narrowing down this list to five finalists and a winner, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, how they view their role as a writer in the cultural and political moment, and the best piece of writing advice they’ve received.

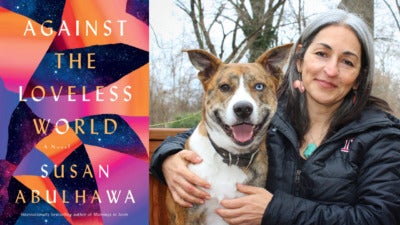

Susan Abulhawa is a Palestinian American writer and political activist. She is the author of Mornings in Jenin and The Blue Between Sky and Water. Born to refugees of the Six-Day War of 1967, she moved to the United States as a teenager, graduated with degrees in biomedical science and neuroscience, and established a career in medical science. Against the Loveless World follows Nahr, a Palestinian refugee turned political prisoner, who tells her story from an Israeli solitary-confinement cell. As the themes of nationalism, radicalized violence, and women’s rights drive the international news cycle, Nahr’s story offers an intimate look at what drives people to extreme actions.

How do you view your role as a writer in this cultural and political moment, and why is the time right for your book?

I belong to an ancient people with documented continuous habitation of one patch of earth over millennia. The cultural and moral fabric of our society formed organically through centuries of conquests, wars, migrations, pilgrimages, religious conversions, intermarriage, rape, oppression, triumph, and all the stuff of our tumultuous fabled land. All of that—all of who we are and were—is slowly being erased, replaced with a tidy, uncomplicated myth that denies we ever existed, as if the past few thousand years never happened. In the west, it is said “Palestinians are an invention” and, famously, “Palestinians don’t exist.”

It is also true that our active or passive resistance, whether violent or non-violent, against the existential terror we have faced for the past century is deemed as terrorism. Our rhetorical resistance is dismissed as anti-Semitism, a label also applied to our friends who dare express even minimal compassion or acknowledgment of Palestinian humanity.

We are cartoons in popular imagination—on the right: terrorists or savages; on the left: pitiable victims or romanticized mythical creatures who can endure the unendurable.

The Palestinian novel, like all our cultural productions, forms a terrain where our fragmented, exiled, occupied, and terrorized society gets to meet its various parts. The stories we commit to paper allow us to bridge the geographic, linguistic, political, economic, and generational borders that arose from our diaspora. It allows us to find each other in our collective trauma, our shared longing for home, and the deeply beautiful culture passed down to us from our foremothers and forefathers.

At a basic level, the novel is an affirmation of our existence and a gravitational force that helps to hold us steady as the land is pulled from under our feet. My own novel is part of this cultural landscape. I wrote it with a singular loyalty to the characters and the authenticity of their dialogues and actions. And that loyalty, by default, makes this book a narrative written for us, our ancestors, generations to come, and anyone who wants to glimpse a small piece of our complicated, vulnerable, and very human lives. Said in another way, this novel does not cater to or even consider the sensitivities of readers, particularly those who cannot abide our indigeneity. It chooses instead the gritty realness of one woman’s trek through what most of the world only understood as headlines, toward a feminist defiance and universal dignity.

What is the core tenet of your book’s philosophy?

It is an aspiration for a social ethos where we all get to have value; where humans and animals aren’t terrorized for profit or supremacist ideals; where we are all afforded the elemental grace of an unmolested home, and the right to fight for it with all our might when it is taken away. The central character of my novel is a woman who struggled all her life against behemoth social and political forces for the right to live a dignified existence, wherein she might have sovereignty over her own fate and her own body.

If you weren’t a writer what would you be?

I wasn’t always a writer, at least not a published one. In fact, my college and graduate education and the first decade of my career were all in biomedical science. I was a biologist, working in the field of neuroscience when I published my first creative essay. (I still occasionally do some freelance writing for medical journals when I need extra income.)

But in my mind now, if I were to cease being a writer, I should like to take up carpentry, and perhaps pick up a few welding skills. I love the company of animals and the peace of gardening, too. So, a carpenter who lives with a lot of animals, a vast garden, and a vast library. Such luxury! Then again, I cannot be too long away from the street, where my comrades always take to, to use their bodies in making the world a bit gentler and more just.

What’s the best piece of advice you’ve received on writing fiction?

The best advice I received on writing came from a musician—Denardo Coleman, son of the late musical genius Ornette Coleman. I had the honor of being in his father’s loft before he died (and actually got to play a bit of pool with him!) when I was writing my second novel. I was replete with self-doubt and impostor syndrome, and I expressed that to Denardo. He said: “all you have to do is create art that feels true to you.” He reminded me that his father at the time of his emergence on the jazz scene was booed off stage, beaten up for his new musical concepts, and was wholly rejected by the jazz establishment (he was terribly ridiculed by giants like Miles Davis, for example). He said, “if my dad had ever paid attention to anything but creating music he felt good about, he wouldn’t have revolutionized jazz the way he did.”

Which books have brought you hope or solace, or expanded your awareness over the last year?

Although I tend to gravitate toward fiction, particularly historic fiction, the two books to list in this answer are, ironically, non-fiction. They are 1) Sylvia Pankhurst: A Natural Born Rebel, by Rachel Holmes, and 2) The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which I first read in my late 20s or early 30s and decided to re-read at 50. The latter changed my life when I first read it. It was instructive to be reminded of a historic figure I’ve always greatly admired, but as a ‘woman of a certain age,’ I could see in his writing the ways in which he was flawed and vulnerable, which made him all the more important to me. The former was a new historical figure in my consciousness. She’s perhaps one of the most badass women of the 20th century that most of us have never heard of. Getting to know her through the history that Rachel Holmes so wonderfully animated for us was profoundly inspiring to me as a woman, as a writer, as a student of history, and as an activist.