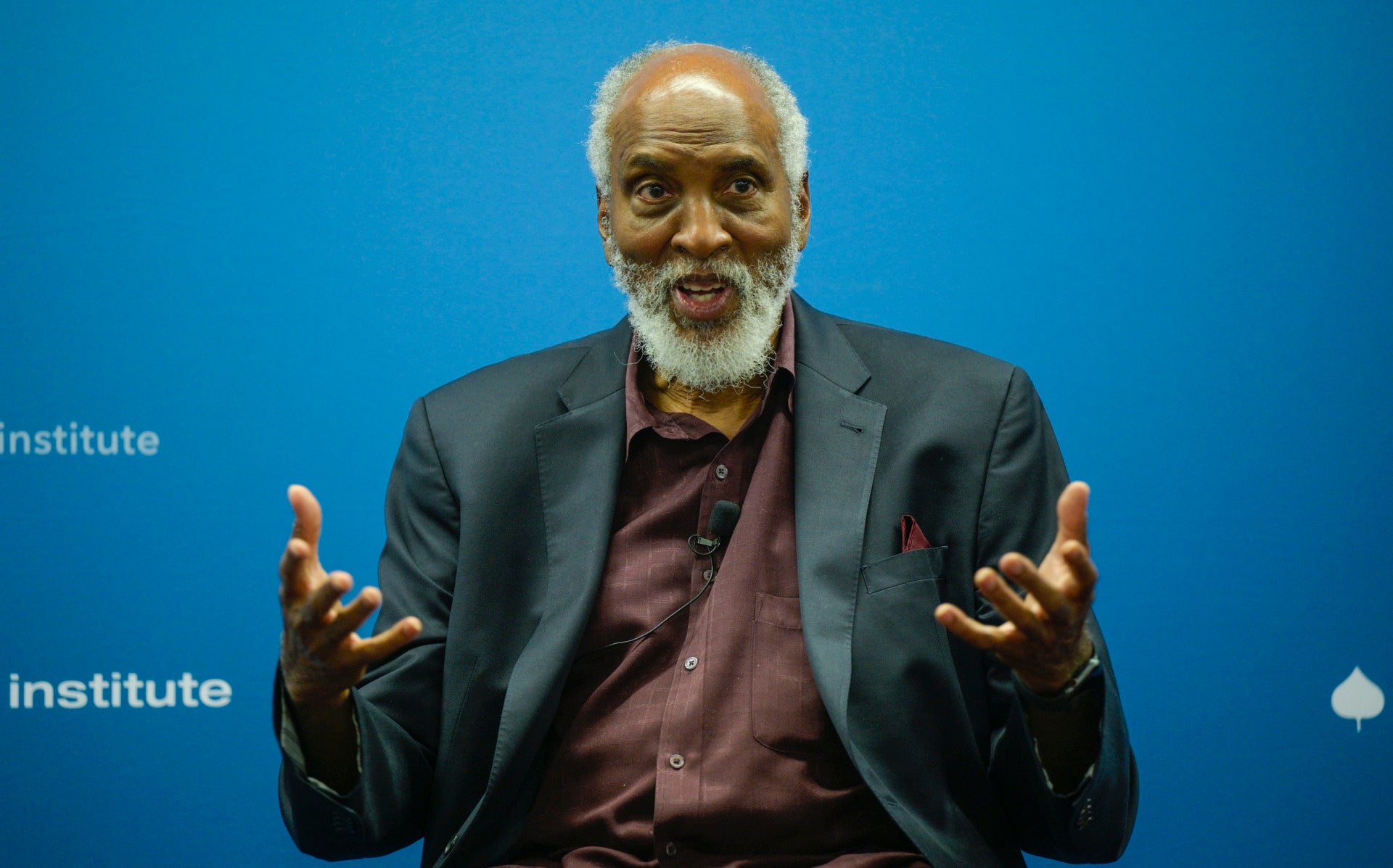

Writers Ta-Nehisi Coates and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie confronted the limits of urbanism at CityLab Paris.

Lagos. New York City. Paris. Baltimore. Washington, DC.

Lagos. New York City. Paris. Baltimore. Washington, DC.

These are some of the grand metropolises that have collectively served as homes to writers Ta-Nehisi Coates and Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. And yet, the two do not identify as urbanists.

“We have to be careful not to romanticize cities,” Adichie said at the CityLab Paris conference. In their conversation with Jeffrey Goldberg, the Editor-in-Chief of The Atlantic, the two writers—well known for their work on issues of race and gender—talked about…well, how we talk about cities.

Urban areas around the world are seen as melting pots—places where by virtue of proximity, residents are forced to confront, and reconcile with, their differences. Squeezing next to people who are from different backgrounds on public transit, for example, is a part of a universal urban acclimation. Coates became used to that while living in New York, he said, and found the familiarity of that experience comforting when he moved to Paris. But at the end of the day, people go back to their homes, and so “you cannot mistake that for real social integration,” he said.

Lagos is Adichie’s home city, and one that features heavily in her fiction. “There’s an energy there that I absolutely love,” she said. But, she added, “it can also feel like people pass one another” on the street without acknowledgement.

When asked where she writes best, she said she prefers “quiet, bland American suburbia” in Maryland, where she can find silence and has a limited social network.

One city she and Coates have very different perspectives on is Paris, the very city where they had this conversation. Coates loves it; as an American, he’s had largely positive experiences. But Adichie is not a fan. As a woman with a West African passport, she has never been treated well in France, she said. Her French friends of African descent are also routinely made to feel like they don’t belong—especially in certain, central parts of Paris. “There is a superiority that I don’t like,” she said. This attitude stems from France’s inability to face that the power dynamics created by its colonial past, and that still persist in its urban spaces today. “The French did not get a memo that they’re no longer a world power,” she said.

Idealizing cities as bastions of progressiveness is a disservice to people living both inside them and outside them, the writers suggested. Conversations about the revitalization of American cities, for example, often hail the “creative class”—a term that often does not include the people of color who have long lived inside these cities, and who have pride and cultural capital in these spaces. (Coates gives the example of go-go, a dance music that originated among black communities in Washington, DC, but that is becoming endangered as the city gentrifies.)

On the other hand, the focus on the rural-urban divide glosses over the fact that African Americans also live in the country—that they have historical ties to rural areas. Ultimately, that divide is a euphemism that doesn’t get get to the heart of the problem at the root of the political rifts in the US, said Coates. “[It’s] a stand-in for other divides that are already there.”

This article originally appeared at CityLab.