In December, Aspen Words announced the longlist for the sixth annual Aspen Words Literary Prize, a $35,000 award recognizing a work of fiction that addresses a vital social issue. The selected books explore the climate crisis, racism, xenophobia, and mental health, and feature a range of dynamic voices. While the jury works on selecting a shortlist, Aspen Words chatted with the nominees about their work, how they view their role as a writer in this cultural and political moment, and the best piece of writing advice they’ve received.

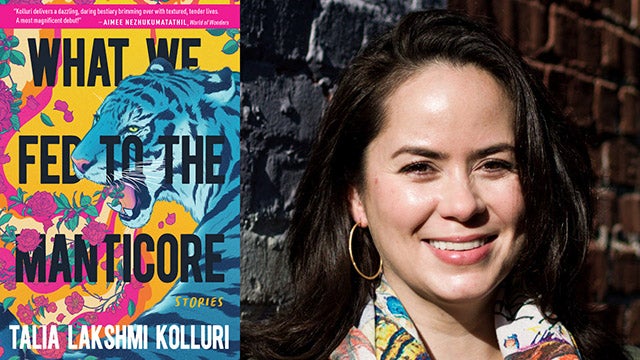

Talia Lakshmi Kolluri was born and raised in Northern California and currently lives in California’s Central Valley. What We Fed to the Manticore is her debut collection. The book explores themes of environmentalism, conservation, identity, belonging, loss, and family with resounding hearts and deep tenderness through nine emotionally vivid stories, all narrated from animal perspectives. Kolluri’s pages speak to the fears and joys of the creatures we share our world with and ultimately place the reader under the rich canopy of the tree of life.

What about our current cultural and political moment inspired you to write What We Fed to the Manticore?

I feel very strongly that human impacts on the environment, which include the climate crisis, are one of the most urgent categories of issues that we immediately need to address on a global scale. Human environmental impacts intersect with everything: economic and racial injustice, food insecurity, oppression of marginalized groups, geopolitics, and more. These impacts pose an existential threat to the well-being and survival of so many creatures on this planet, including humanity. Their reach is long, and it spans across distances and through time, both deep into our past and extending far into our future.

I often feel very powerless against all of the history and systems that have brought us to this point, and when I feel powerless, I feel hopeless. And then I step outside, and I see a hummingbird, or a trail of ants, or bees hovering above flowers. I smell the earth after rain. And I think, “Ah yes, here we are.” We, the ants, the bees, the hummingbird, the flowers, and me. I wanted my book to take readers by the shoulders and plunge them headfirst into the life that surrounds us. I wanted it to demand attention to nature, to insist that we attend to it because we are of it.

Can you share an experience that taught you the power of language?

When I was a teenager, we were given a book in English class that was part of a standard curriculum. One student asked for something different to read because her parents said she wasn’t allowed to read what was assigned. I don’t remember what book it was or if the teacher gave her something else, but what I do remember is my own reaction of being absolutely astonished at the idea of not being allowed to read something.

When I was a child, I often spent hours of unsupervised time in the public library reading continuously, until I had plowed through everything for kids my age and moved on to see what books were available to adults. At home, I read whatever I wanted without restriction. I was a voracious reader, so that included almost every book in the house, from medical reference books to romance novels. Reading was indisputably a sanctuary, an entertainment, and a pathway to a limitless life for me. The notion of hearing “no” to my chosen reading was a foreign concept that I couldn’t understand.

When I heard my classmate ask for another book, I wondered what exactly was contained in this novel that her parents didn’t want her to know. I felt by not reading it, she would be at some sort of disadvantage because all the rest of us would have knowledge that she had no access to. The notion of the absence of words is what showed me their power. I think of this again now as we see waves of book banning streaking across this country, and as we see access to education, which fundamentally is access to language about all kinds of things, being restricted in various ways across the world. Language is the gateway through which we step toward knowledge, information, and context. And through knowledge comes liberation. I don’t think there is anything more powerful.

How did the process of writing this book change you?

I hope that I have been transformed into a more attentive person. I wrote this collection over the course of a decade, and during that time, landscapes have been transformed, entire species have been declared extinct or brought to the brink of extinction, seasons feel different, and the passage of time has been written on my face, my body, and my life. I am struck more and more by the impermanence of everything. This may have been a function not only of the stories I chose to write, but also of the phases of my life and the particular time in which I was writing, but I found at the end of the process that I was acutely aware of both my own individual insignificance and my mortality.

I also became much more aware of the interconnectedness and the fragility of our environment, including the living systems that are still a mystery to us. Our world is delicate, and we are careless with it and with all the lives that reside in it, both human and non-human. With every creature I researched, I learned just how precarious everything is. This book was fueled by curiosity and a sense of wonder, but in the end, what I think I produced is a book of mourning. This has begun to mean that I feel extreme urgency about paying attention to the world around me because I want to bear witness to the world as it is, even as we transform it into something we may not recognize.

Which of the characters did you find most difficult to write?

The most challenging character for me to write was the whale narrator in “The Open Ocean Is An Endless Desert.” Whales’ sensory systems are so interesting because they use physiology that seems similar to ours such as eyes and ears, but with wildly different effects when the information is taken in. During my research process, I learned that the interior bones of a whale’s ears are essentially floating inside their heads which allows them to more precisely pinpoint the direction of sounds underwater and that while they can see, their vision is significantly more limited in sharpness ours.

To complicate things further, I wrote from the point of view of a baleen whale, and there are some features of their hearing that are less well understood than for toothed whales. All this to say, I was writing a character who lives in a completely different environment from my own, and understands his surroundings through a soundscape which is very far from my own experience. I also understand that life in the water column in the open ocean includes a lot of expansive space for a whale, and daily life doesn’t often include close quarters with other creatures. It may seem like an isolated life, but it isn’t because so much of their perception is based on sounds heard across long distances. To write this story, I needed to reframe that perception for myself. It absolutely stretched my imagination to write as a whale, but I’m so happy that I chose to do it.

What was the last book you couldn’t put down?

This past year I read The Immortal King Rao, by Vauhini Vara and I had been looking forward to it for months. Vara is such an interesting and innovative writer and I felt that so much of this novel was for me in a way that few books are. Set in parallel timelines, she weaves several themes together examining caste in South India, evolving immigrant identities, complex father-daughter relationships, the creeping influence of technology, solitude while mourning, and dissolving democracy all against the backdrop of “hothouse earth.” It’s brilliant and I’ll be returning to it many times.