The United States may be facing the most severe housing crisis in its history. According to the latest analysis of weekly US Census data, as federal, state, and local protections and resources expire and in the absence of robust and swift intervention, an estimated 30–40 million people in America could be at risk of eviction in the next several months. Many property owners, who lack the credit or financial ability to cover rental payment arrears, will struggle to pay their mortgages and property taxes and maintain properties. The COVID-19 housing crisis has sharply increased the risk of foreclosure and bankruptcy, especially among small property owners; long-term harm to renter families and individuals; disruption of the affordable housing market; and destabilization of communities across the United States.

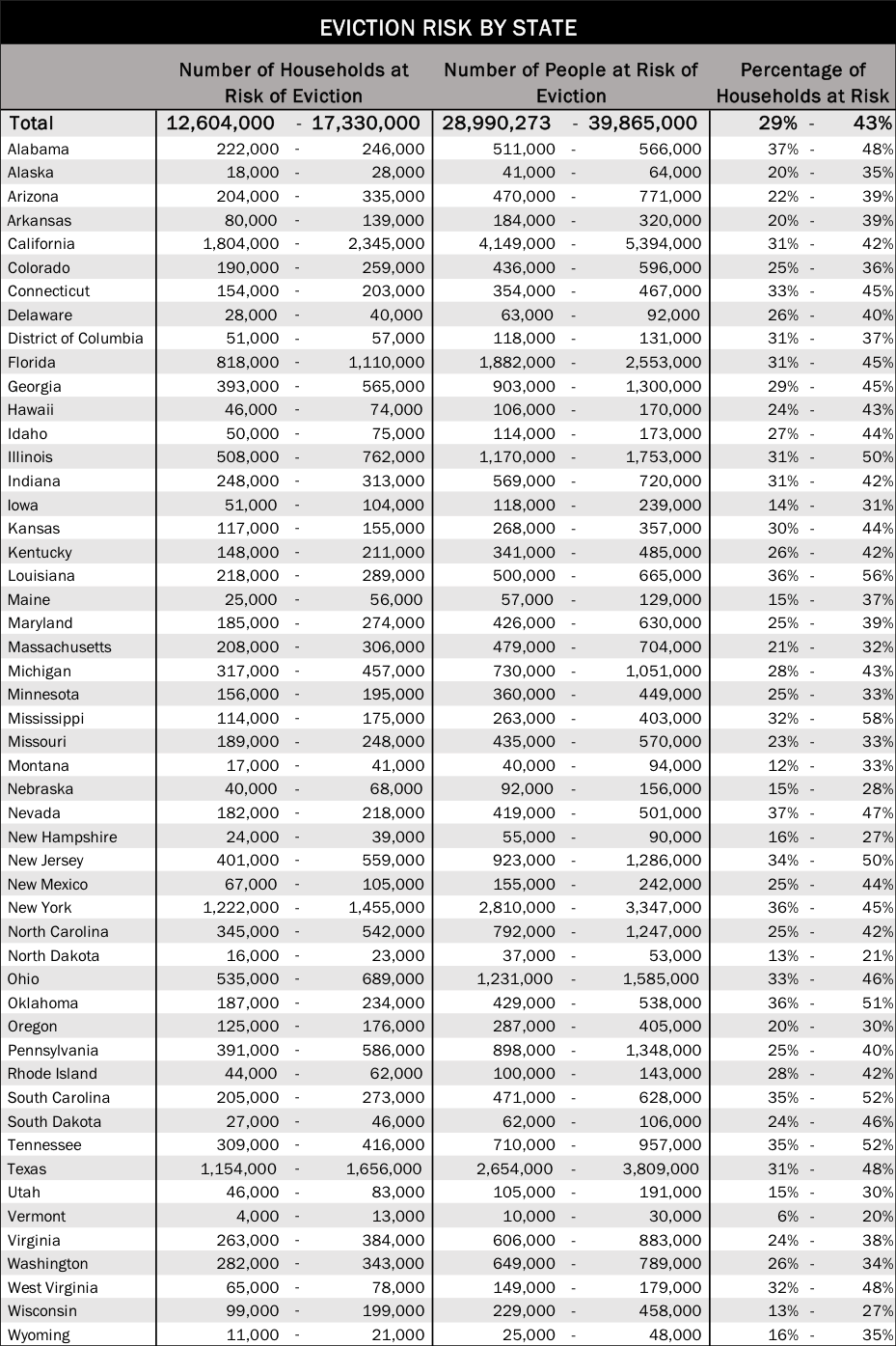

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers, academics, and advocates have conducted a continuous analysis of the effect of the public health crisis and economic depression on renters and the housing market. Multiple studies have quantified the effect of COVID-19-related job loss and economic hardship on renters’ ability to pay rent during the pandemic. While methodologies differ, these analyses converge on a dire prediction: If conditions do not change, 29-43% of renter households could be at risk of eviction by the end of the year.

This article aggregates the existing research related to the COVID-19 housing crisis, including estimated potential upcoming eviction filings, unemployment data, and housing insecurity predictions. Additionally, based on this research and new weekly analysis of real-time US Census Bureau Household Pulse data, this article frames the growing potential for widespread displacement and homelessness across the United States.

The COVID-19 pandemic struck amid a severe affordable housing crisis in the United States

COVID-19 struck when 20.8 million renter households (47.5% of all renter households) were already rental cost-burdened, according to 2018 numbers. Rental cost burden is defined as households who pay over 30% of their income towards rent. When the pandemic began, 10.9 million renter households (25% of all renter households) were spending over 50% of their income on rent each month. The majority of renter households below the poverty line spent at least half of their income towards rent in 2018, with one in four spending over 70% of their income toward housing costs. Due to chronic underfunding by the federal government, only one in four eligible renters received federal financial assistance. With the loss of four million affordable housing units over the last decade and a shortage of 7 million affordable apartments available to the lowest-income renters, many renters entered the pandemic already facing housing instability and vulnerable to eviction.

Before the pandemic, eviction occurred frequently across the country. The Eviction Lab at Princeton University estimates that between 2000 and 2016, 61 million eviction cases were filed in the US, an average of 3.6 million evictions annually. In 2016, seven evictions were filed every minute. On average, eviction judgment amounts are often for failure to pay one or two months’ rent and involve less than $600 in rental debt.

An increase in evictions could be detrimental for the 14 million renter households with children: research from Milwaukee indicates that renter households with children are more likely to receive an eviction judgment. Although tenants with legal counsel are much less likely to be evicted, on average, fewer than 10% of renters have access to legal counsel when defending against an eviction, compared to 90% of landlords.

At the same time, a lack of rental income places rental property owners at risk of harm. Individual investors, who often lack access to additional capital, may be particularly vulnerable. Presently, while “mom and pop” landlords own 22.7 million out of 48.5 million rental units in the housing market, more than half (58%) do not have access to any lines of credit that might help them in an emergency. Landlords who evict tenants face court costs, short or long term vacancy, reletting costs, and the loss of 90-95% of rental arrears via sale to a debt collector or other third party. In the short term, lack of rental income may result in unanticipated costs, and an inability to pay mortgages, pay property taxes and maintain the property. In the long term, it places small property owners at greater risk of foreclosure and bankruptcy.

Communities of color are hardest hit by the eviction crisis

Communities of color are disproportionately rent-burdened and at risk of eviction. People of color are twice as likely to be renters and are disproportionately likely to be low-income and rental cost-burdened. Studies from cities throughout the country have shown that people of color, particularly Black and Latinx people, constitute approximately 80% of people facing eviction. After controlling for education, one study determined that Black households are more than twice as likely as white households to be evicted. In a study of Milwaukee, women from Black neighborhoods made up only 9.6% of the city’s population but accounted for 30% of evicted tenants. In Boston, 70% of market-rate evictions filed were in communities of color, although those areas make up approximately half of the city’s rental market. Researchers from UC Berkeley and the University of Washington found the number of evictions for Black households in Baltimore exceeded those for white households by nearly 200%, with the Black renter eviction rate outpacing the white renter eviction rate by 13%. In New York City, a sample of housing court cases indicated that 70% of households in housing court are headed by a female of color, usually Black and/or Hispanic. In Virginia, approximately 60% of majority Black neighborhoods have an annual eviction rate higher than 10% of households, approximately four times the national average, even when controlling for poverty and income rates. In Cleveland, the top ten tracts for eviction filings from 2016-2018 were all majority Black tracts; only six had poverty rates above 10%.

Similarly, people of color are most at risk of being evicted during the COVID-19 pandemic. A report co-authored by City Life/Vida Urbana and Massachusetts Institute of Technology showed that in the first month of the Massachusetts state of emergency, 78% of eviction filings in Boston were in communities of color.

COVID-19 job and wage losses could create an unprecedented and long-term housing crisis

The economic recession, coupled with job and wage loss, magnified and accelerated the existing housing crisis. As of July 2020, nearly 50 million Americans have filed for unemployment insurance. Between March and July, unemployment rates fluctuated between 11.1% and 14.4%. By comparison, unemployment peaked at 10.7% during the Great Recession. More than 20 million renters live in households that have suffered COVID-19-related job loss. This job loss is exacerbated by the recent expiration of pandemic unemployment insurance benefits across the country. With federal legislators in a stalemate regarding how or if to extend benefits, unemployed renters are at an even greater risk of financial constraints leading to eviction.

Job loss is affecting people of color at much higher rates than their white counterparts. Initial numbers from April highlight this disparity: 61% of Hispanic Americans and 44% of Black Americans said that they, or someone in their household, had experienced a job or wage loss due to the coronavirus outbreak, compared with 38% of white Americans. People with disabilities (who have historically higher rates of unemployment than the general population), LGBTQ people (who experience homelessness at a disproportionate rate), and undocumented immigrants (who do not qualify for unemployment insurance or receive stimulus checks), could all be at heightened risk of economic hardship during the pandemic.

In the early weeks of the pandemic in the US, researchers at the Terner Center at the University of California, the Urban Institute, the Joint Center for Housing at Harvard, the National Low Income Housing Coalition, and the Furman Center at NYU separately estimated the number of at-risk renter households employed in jobs that were most vulnerable to COVID-19-related job loss. Together, these studies concluded that between 27% and 34% of renter families were at risk of job or wage loss.

Renters experiencing cash shortages are increasingly relying on sources other than income to pay rent. Thirty percent of renters report using money from government aid or assistance to pay rent, and another 30% indicate that they have borrowed cash or obtained a loan to make rental payments. Tenants are increasingly using credit cards to pay the rent, with a 31% increase between March and April, an additional 20% increase from April to May, and a 43% increase in the first two quarters as compared to the prior year. There is increasing evidence that families are shifting their budget towards rent. Food pantry requests have increased by as much as 2000% in some states, with nearly 30 million Americans reporting they do not have enough food.

Evidence indicates that rental payments are decreasing during the pandemic. The National Multifamily Housing Council (NMHC) reported that 88% of tenants had paid July’s rent by mid-month—less than both June 2020 and July 2019. Apartment List estimates that 36% of renters missed July payments. According to Avail, an online payment platform for midsize independent landlords and their tenants, only 55% of landlords using the platform received full rent payments in July.

NMHC and the National Apartment Association informed Congress in April that “more than 25 percent of the households that rent in the US may need help making payments” because of COVID-19 rental hardship, translating to nearly 11 million households and 25 million people. In a study based on predicted job and wage loss, the Aspen Institute Financial Security Program and the COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project projected that 19 to 23 million renters in the United States are at risk of eviction through the end of 2020, representing up to 21% of renter households. Similarly, Amherst Capital, a real estate investment firm, estimated in June that 28 million households (64 million people) are at risk of eviction due to COVID-19.

Temporary protections against evictions during the COVID-19 pandemic have largely expired across the US

Federal, state, and local eviction moratoriums provided important protections for some renters, but they are expiring rapidly. In the first month of the pandemic, the federal government instituted a limited moratorium on evictions in federally-assisted housing and for properties with federally backed mortgages. The federal eviction moratorium protected about 30% of renters. Various actors in forty-three states and the District of Columbia issued eviction moratoriums that varied in level of protection and stage of eviction stopped. Those state-level protections ranged from a few weeks to a few months in duration and did not apply to all evictions. The Eviction Lab’s Eviction Tracker System indicates that eviction moratoriums were effective in reducing eviction filings when they were in place. Federal protections expired on July 24th. As of July 31st, 30 states lack state-level protections against eviction during the pandemic.

According to the COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard, created by the Eviction Lab and Professor Emily Benfer, the vast majority of states lack protective eviction moratoriums and housing stabilization measures that could support renters facing rent hardship. As a result, tenants unable to pay their rent due to the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic are receiving eviction notices, and courts across the country have resumed eviction hearings, in many cases via video conference. Global advisory firm Stout Risius Ross, LLC (Stout) estimates that 11.6 million evictions could be filed in the US in the next four months.

States, counties, and cities have offered limited emergency rent assistance to renters and landlords by using funding provided in the CARES Act via Community Development Block Grants and the Coronavirus Relief Fund, as well as other funding sources. However, according to an analysis by the National Low Income Housing Coalition, the need has overwhelmed many of these programs, as demonstrated by the use of lottery systems, and the closure of three out of 10 programs (some within minutes of opening).

The risk of eviction could escalate rapidly across America

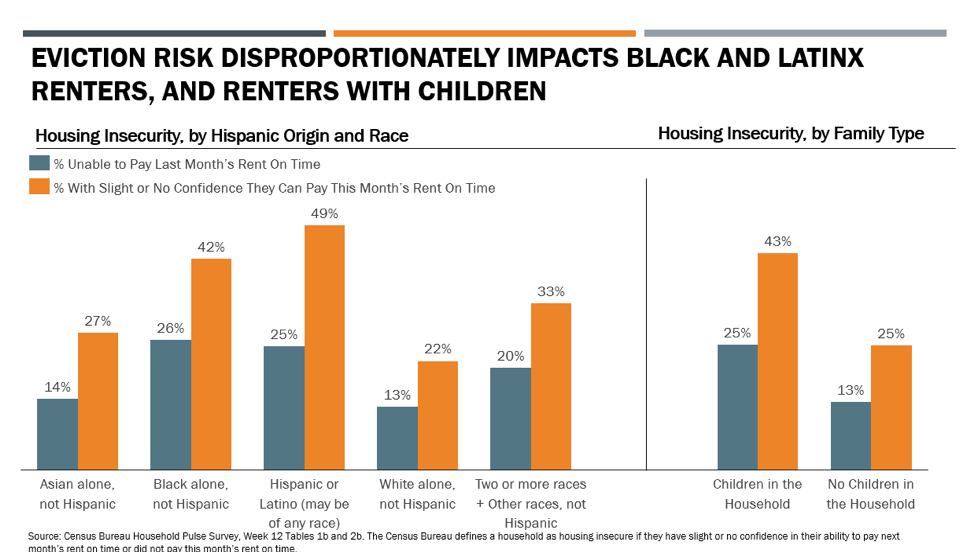

According to the most recent US Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey (Week 12), 18.3% of renters nationally report that they were unable to pay July’s rent on time. Forty-three percent of renter households with children and 33% of all renter households have slight or no confidence that they can pay August rent on time. Among renter households earning less than $35,000 per year, 42% have slight or no confidence in their ability to pay next month’s rent.

Black and Latinx populations consistently report low confidence in the ability to pay rent during the pandemic. The Census Bureau’s Week 12 Housing Pulse Survey indicates that nearly half of Black (42%) and Hispanic (49%) renters have slight or no confidence in their ability to pay next month’s rent on time, a figure that is twice as high as white renters (22%). Moreover, 26% of Black renters and 25% of Hispanic renters reported being unable to pay rent last month, compared to 13% of white renters.

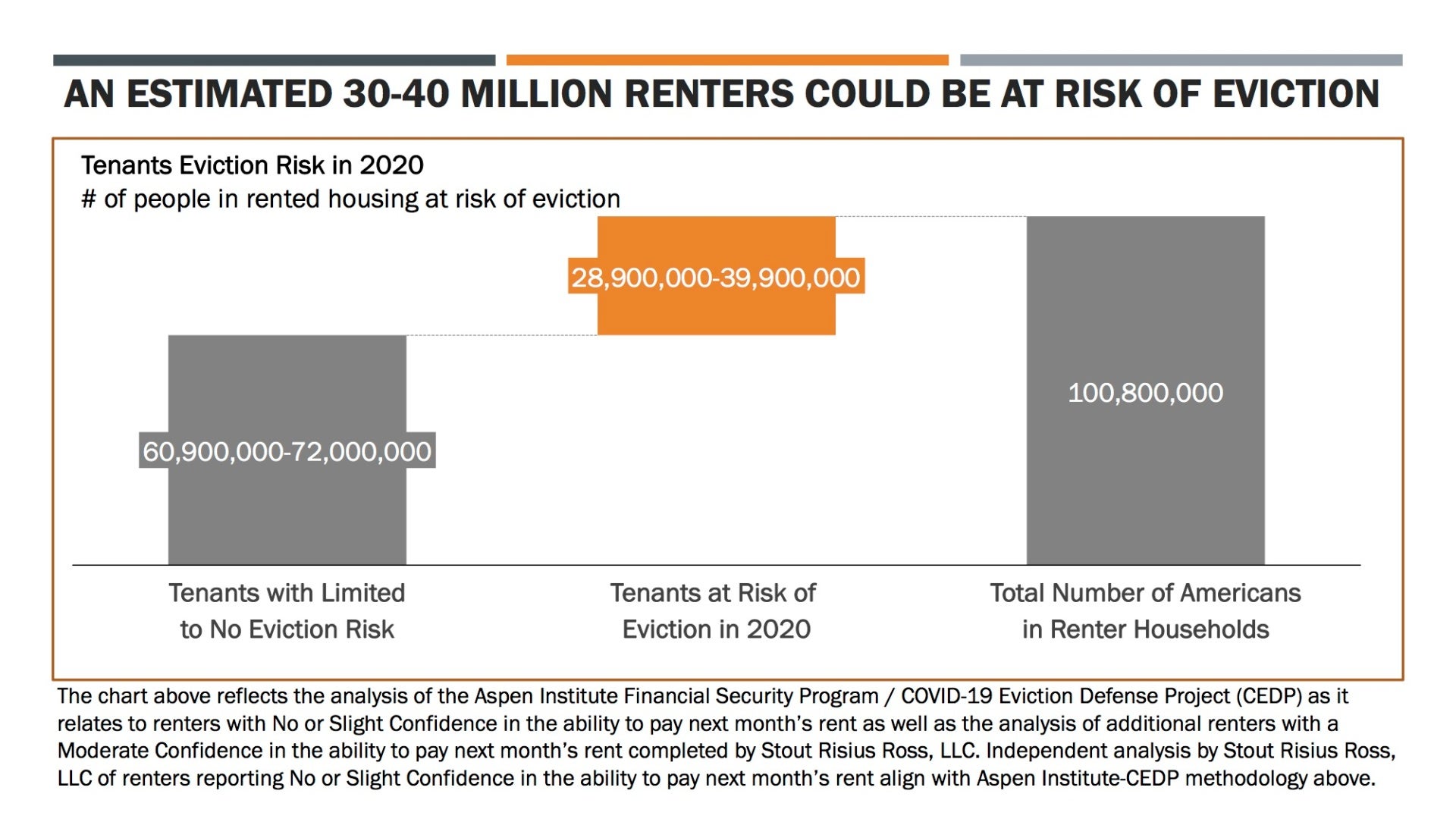

Current projections indicate that America is facing an urgent and unprecedented eviction crisis. In an updated analysis of the US Census Bureau’s Pulse Survey, based on renter’s perceptions of their ability to pay, the Aspen Institute Financial Security Program and the COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project currently estimate that 29 million renters in 12.6 million households may be at risk of eviction by the end of 2020. Stout anticipates that up to 40 million people in more than 17 million households may be at risk of eviction through the end of the year when considering a portion of survey respondents who have a “moderate” degree of confidence in the ability to pay rent (in addition to those with slight or no confidence). Both projections rely on renter perceptions of their ability to pay measured by the Pulse Survey.

The chart below reflects the analysis of the Aspen Institute Financial Security Program and the COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project as it relates to renters with No or Slight Confidence in the ability to pay next month’s rent, as well as the analysis of additional renters with a Moderate Confidence in the ability to pay next month’s rent completed by Stout. Stout’s independent analysis of renters reporting No or Slight Confidence in the ability to pay next month’s rent aligns with the Aspen Institute analysis presented below.

The COVID-19 housing crisis could devastate small property owners, tenants, and communities

Significant loss of rental income during the COVID-19 pandemic creates financial peril and hardship for renters, small property owners, and communities. Without rental income, many landlords may struggle to pay mortgages and risk foreclosure and bankruptcy. The National Consumer Law Center predicts that 3 million homeowners, or roughly 5%, will have significantly delinquent mortgages by early 2021. Currently, 44% of single-family rentals have a mortgage or some similar debt. Sixty-five percent of properties with 2 to 4 units and 61% of properties with 5 to 19 units have a mortgage. Foreclosure can lead to a lack of maintenance, urban blight, reduced property values for neighboring properties, and erosion of neighborhood safety and stability. Without rental income to pay property tax, communities lose resources for public services, city and state governments, schools, and infrastructure, and can expend significant resources managing or disposing of properties acquired through tax foreclosure.

The impact of an eviction on families and individuals is even greater. Following eviction, a person’s likelihood of experiencing homelessness increases, mental and physical health are diminished, and the probability of obtaining employment declines. Eviction is linked to numerous poor health outcomes, including depression, suicide, and anxiety, among others. Eviction is also linked with respiratory disease, which could increase the risk of complications if COVID-19 is contracted, as well as mortality risk during COVID-19. Eviction makes it more expensive and more difficult for tenants who have been evicted to rent safe and decent housing, apply for credit, borrow money, or purchase a home. Instability, like eviction, is particularly damaging to children, who suffer in ways that impact their educational development and well-being for years.

The public costs of eviction are far-reaching. Individuals experiencing displacement due to eviction are more likely to need emergency shelter and re-housing, use in-patient and emergency medical services, require child welfare services, and experience the criminal legal system, among other harms.

Proposed policy interventions avoid suffering, save lives, and prevent severe harm

The eviction crisis and its devastating outcomes are entirely preventable. Policy interventions at the national, state, and local levels could avoid many of the devastating costs outlined above. The COVID-19 Housing Policy Scorecard, Eviction Innovations, and national and local housing rights groups offer many different eviction prevention options that are available and being considered by policymakers. However, without federal financial assistance, any intervention will be a stopgap at best and may fail to prevent the eviction crisis and its collateral harm.

The most comprehensive policy proposals include a nationwide moratorium on evictions and at least $100 billion in emergency rental assistance. Combining this assistance with an extension of federally enhanced unemployment insurance for displaced workers would provide additional relief for renters. Responses like these could neutralize the eviction risk outlined in this report, eliminating the public and private costs of mass evictions that result from the pandemic. More importantly, they could prevent millions of people in America from experiencing unfathomable hardship in the months and years ahead. These solutions have passed the US House of Representatives two times, and have companion legislation in the Senate.

Similarly, studies have shown a civil right to counsel in eviction cases can deliver significant benefits for tenants and landlords. While exact figures vary by jurisdiction, tenants with counsel experience improved housing stability—often by remaining in their home, but alternatively by obtaining additional time to relocate, avoiding a formal eviction on their record, and accessing emergency rental assistance or subsidized housing. Representation also leads to lower default rates and more fairly negotiated resolutions with landlords that limit disruption from displacement and ensure the rights of all parties are exercised. Other policies, such as eviction record sealing and restrictions that preclude property owners from basing tenant eligibility on eviction records, can prevent the longer-term harm that comes from eviction.

Given the incredibly high cost of evictions to renters, landlords, and communities, a wide range of policy interventions would provide significant cost avoidance for state and local government across the US

Conclusion

Renters experiencing financial hardship due to COVID-19 have exhausted their resources and limited funds just as eviction moratoriums and emergency relief across the United States expire. Without intervention, the housing crisis will result in significant harm to renters and property owners. Meaningful, swift, and robust government intervention is critical to preventing the immediate and long-term negative effects of the COVID-19 housing crisis on adults, children, and communities across America.

Authors

- Emily Benfer, Wake Forest University School of Law

- David Bloom Robinson, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Stacy Butler, Innovation for Justice Program, University of Arizona College of Law

- Lavar Edmonds, The Eviction Lab at Princeton University

- Sam Gilman, The COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project

- Katherine Lucas McKay, The Aspen Institute

- Zach Neumann, The Aspen Institute / The COVID-19 Eviction Defense Project

- Lisa Owens, City Life/Vida Urbana

- Neil Steinkamp, Stout

- Diane Yentel, National Low Income Housing Coalition