![]()

I was 11 the first time my body was grabbed, smacked, and slapped.

While I walked to class, boys groped me. While I sat at my desk, boys “accidentally” touched my chest. By 12, groups of male classmates called me to ask if I touched myself. By 13, it escalated to requests for pictures of my body. I hadn’t yet been exposed to language that could describe my experiences – words like objectification and misogyny. It made it difficult for me to not only understand what was happening and why, but to vocalize my protests. Teachers’ and administration’s silence towards myself and others in similar situations was a missed opportunity for course correction. This enabled their behavior in and out of school to continue — and worsen.

#MeToo has shone a light on the prevalence of harassment and assault, and solutions are slowly emerging. While this progress deserves to be celebrated, it has been made almost exclusively by and for adults. These issues don’t suddenly appear when we turn 18, begin college, or enter the workforce. By ignoring young people’s experiences, we fail to create solutions that address the unique problems they face. K-12 schools can work to proactively prevent harassment and assault by integrating consent into their sex education courses.

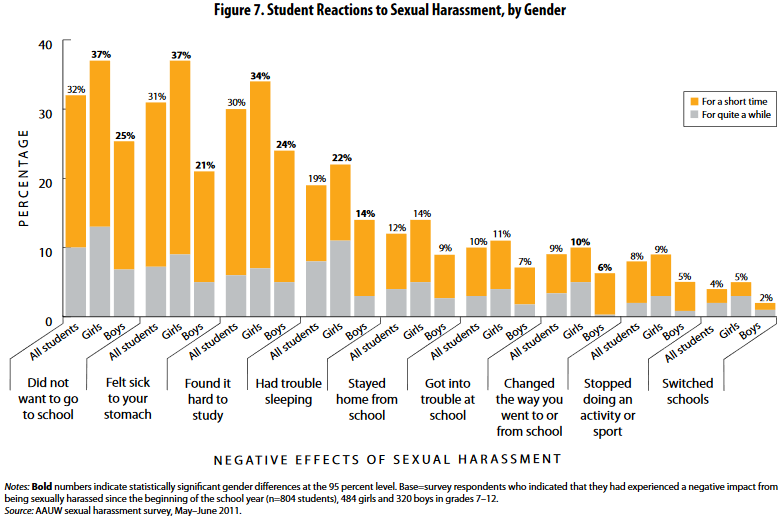

As is the case for adults, harassment and assault among youth is gravely underestimated. Forty-Two percent of female rape survivors were under 18 years old when they were first raped, and 28 percent of male survivors were first raped when they were 10 or younger. Compared to the general population, girls ages 16-19 are four times more likely to be victims of rape or attempted rape. Forty-Eight percent of 7th-12th graders have experienced gender-based harassment during the school year. A refusal to talk about or solve these issues is an infantilizing denial of the realities that young people face. Our lack of trust in their readiness to have these conversations is a disservice that directly impacts academic achievement and emotional well-being.

California remains the only state that requires affirmative consent education for high school students. Our insistence on not talking about consent until college, if ever, ignores the amount of time it takes to unlearn problematic beliefs surrounding gender and sexuality. It neglects younger students who will benefit from this information, and exacerbates inequities considering many young people will never attend college. Beginning consent education early on is essential to building a foundation through which positive habits and beliefs can be applied to new situations as children develop socially. Age-appropriate, non-sexual lessons – such as teaching children they shouldn’t tickle someone who has asked them to stop – lay the groundwork for bodily agency, how to vocalize this agency, and the expectation that this vocalization should be heard.

When consent is integrated into sex education, new topics can be included such as abuse; identifying, expressing, and receiving verbal and non-verbal consent and non-consent; bodily autonomy; rape myths; bystander intervention; and resources for rape survivors. This provides students with skills to engage in healthy sexual and non-sexual relationships, identify unhealthy ones, and recognize issues in their own behavior.

It’s important to note that consent education should not be taught in ways that merely reaffirm existing gender-power dynamics and heteronormativity. Many conversations about sexual assault prevention subscribe to the gatekeeper myth, by which men instigate sex and women are supposed to resist if it is unwelcomed. By obeying a laundry list of actions and inactions, one can purportedly prevent their own rape. This teaches young people that rape is to be avoided, rather than not committed. Keeping these issues in mind, educators should emphasize that consent education is not merely about the legal boundaries of sexual interactions, but about a shift in the ways we view power, gender, sexual orientation, and interpersonal relationships altogether.

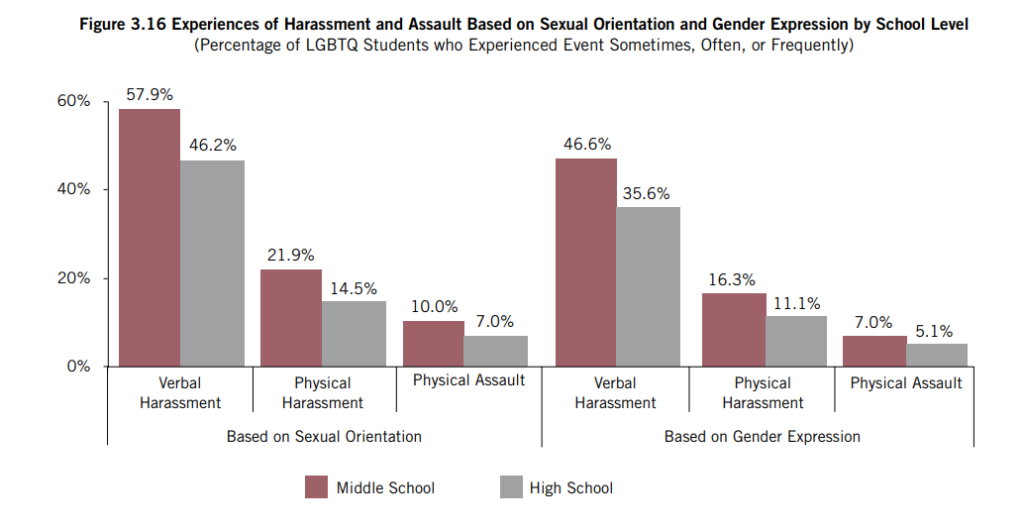

We also see instances where LGBTQ+ relationships are either ignored or demonized in sex education. Seven states actually require that it be portrayed negatively. This is especially harmful considering 43 percent of LBG and 89 percent of trans youth have experienced physical dating violence, as compared to 29 percent of cisgender, heterosexual youth.

To be sure, consent is not the antithesis of abstinence – consent education benefits those who choose to be sexually active as well as those who choose to wait. Being abstinent requires the ability to vocalize the “no” that consent education teaches, as well as partners who respect those boundaries. For those who are not sexually active, but will be in the future, consent education also provides a toolbox that can be reached into when needed. Those tools are especially important considering 59 percent of men believe husbands are entitled to sex with their wives, and 46 percent believe boyfriends are entitled to sex with their girlfriends. Additionally, harassment and abuse can be committed by and happen to youth who are not sexually active. Ultimately, all youth need consent education regardless of what sexual choices they make.

A #MeToo movement with an age limit is inadequate and ineffective. Youth remain unsafe and schools continue to be incubators for harmful behavior. We must reach the problem at its root. Solutions cannot merely impact youth. Students are both the primary stakeholders and the experts in their own experiences, making it imperative that they are the drivers of change. Faculty must ask students what is happening in and out of school and what can be done about it. A seat at the table that is safe and confidential allows schools to be knowledgeable about and therefore effective in responding to the problems students face.

My experiences in school were not an anomaly. Unless we listen and take action, students like me will continue to have their academic careers and personal lives impacted by harmful school environments. Consent education is not a panacea, but rather one of many possible and necessary steps to creating change. If we want sustainable solutions to #MeToo, young people’s needs must be at the forefront of the movement.