Demond Drummer is co-founder of CoderSpace, where youth ages 14-17 learn to code and develop leadership skills for a changing world. He was previously a tech organizer on the South Side of Chicago, where he facilitated digital leadership trainings with block clubs, parent groups and business owners.

This interview is part of the Aspen Institute Center for Urban Innovation’s series of conversations with inclusive innovation practitioners.

Jennifer Bradley: How do you think about the relationship between tools and values?

Demond Drummer: First of all, I love this question.

Demond Drummer, Co-founder, CoderSpace

There’s this idea that tools and technology are morally neutral. That’s a comforting falsehood. All the tools and technology we have in front of us are infused with values and laden with biases that reinforce existing patterns of power, access, opportunity, voice, et cetera. And so, it’s important that we first acknowledge that reality, and then be very intentional about what tools we use and how we use them.

For example, while American slave owners used the Bible to indoctrinate the Africans they enslaved, those who were in bondage brought their visions of liberation to that same Bible and produced readings that pointed toward freedom.

So it’s not enough to simply adopt the tools in front of us, we have to appropriate them for our own purposes. You can call this “hacking” if you want.

All the while we must remember Audre Lorde’s warning: “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”

JB: What are the tools that you use?

DD: A powerful tool I use in everything I do is the one-to-one relational meeting. There’s nothing like intentionally relating to someone else by sharing my story and seeking to understand their story, their motivations, their values–namely, the “why” behind what they do. Sometimes I skip over this crucial step for the sake of expediency. But I’ve learned that starting with this genuine conversation–steering it back to these fundamental questions–builds working relationships that are stronger, more productive and more sustainable.

A project like Large Lots in Chicago–something we did in Englewood and has since taken on a life of its own–doesn’t happen because of new technology or some standard insincere public input process. A successful project like this can only emerge from a web of strong working relationships developed over time. Only through one-to-one relationship building can you bridge divides of historic and legitimate mistrust, get everybody in the room and decide that we will get this one policy changed.

Part of the CoderSpace application process involves an interview. We say it’s an interview, but it’s actually a relational meeting with the youth applicant and their family. It’s extremely time intensive and absolutely necessary. Building a foundation of trust gives us room to take risks together as a learning community. This is how we have a 97% retention rate over three years, even as we iterate and refine the program.

One-to-one interactions. That’s the currency of inclusive innovation.

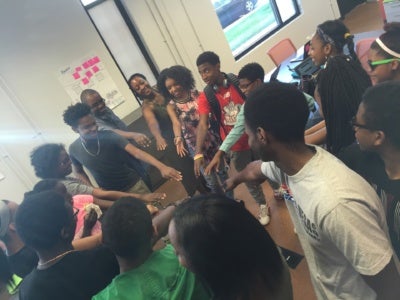

Courtesy of CoderSpace

JB: Which tool do you not use?

DD: In-person conversations and interactions are far more meaningful and productive for me, so I avoid using digital means of communicating whenever practical. I try to get as close to that in-person connection as possible.

JB: What is a tool that you wish existed, but doesn’t?

DD: At the Obama Foundation Summit I sat next to a dance professor who shared with me how she uses the technology of the circle in her teaching. My spirit lit up because this is what we do at CoderSpace. The circle is an Indigenous technology that opens space for learning and co-production–whether the subject be dance or computer science. The circle is egalitarian and inclusive. Some may be learning while others may be teaching, but everyone has something to contribute to what we’re creating together.

The hardest part of CoderSpace is living out our values in spaces that are not designed with our values in mind. Linear classrooms say, “Look to the front where the instructor is standing,” when in fact we want students to look to each other–because that’s how real learning happens.

Courtesy of CoderSpace

I wish more learning spaces, more organizations, more government agencies and public processes were designed around the technology of the circle.

JB: How should we think differently about tools?

DD: Don’t think about the tools! The tool is a secondary question. It comes back to values. What are you trying to accomplish and why? How do you want to work and why? And then you situate whatever tools you may appropriate or create into that frame of thinking.

I root my work in the theory and practice of Septima Clark. Septima Clark was a teacher in Charleston, SC who was fired from her job because she was a member of the NAACP. This was 1956. The school board fired her, but she didn’t stop teaching. Living under a Jim Crow regime that used literacy tests to prevent black people from voting, Clark developed citizenship schools to teach literacy as a means to power.

So for me, digital literacy and computer science education are a means to power. Even though the vast majority of CoderSpace youth go on to study computer science in college, I’m becoming less interested in how many of our students pursue careers in technology. What’s more interesting to me is how we can use technology and computer science as a context in which youth can practice different habits of mind and modes of production that are increasingly relevant in a rapidly changing world.

We constantly challenge our youth to apply what they’re learning to whatever it is they are most passionate about. We don’t want them to simply keep up with the pace of change. We want them to use their experience, their questions, their values to drive the change in whatever field they ultimately choose.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This blog series is supported by the Citi Foundation, a vital early supporter of the Center for Urban Innovation at the Aspen Institute. With the Citi Foundation’s help, the Center convened leading-edge practitioners to develop a shared set of principles to guide a cross-sector approach to inclusive innovation in low- and middle-income neighborhoods, and to determine how the Aspen Institute could support this practice.