Photo Credit | iStock Photos

As coverage of another presidential election overtakes airwaves, neither of us were surprised to see the media seize on the story of generational divide in voting patterns. Young women are betraying their feminist foremothers by “feeling the Bern” and older women have yet to get with the times, where economic issues are as important as what chromosomes a leader claims. Or so the overly reductive narrative tells us.

The generational rift makes for sensational headlines, but falls short of understanding the full range of issues that are important to women of all ages — not to mention races, classes, religions, and abilities. Women are not a monolith — should that really still strike the mainstream media as clickbait?

The women’s movement has and continues to be a big tent movement — interested in wage parity alongside climate change, affordable childcare alongside sexual freedom, global health alongside criminal justice. Why? Because while women are not a monolith, they do understand one thing pretty universally: all issues are interconnected. You pull one snag and the whole world unravels.

That’s good sense, but it doesn’t make for easy movement building. After all, if you can’t tackle issues in silos, it makes it harder to create finite goals for impact. While the women’s movement worldwide has been strengthened by its nuanced understanding of how identities and issues overlap, it has often slowed us down when setting agendas and finding consensus for collective action.

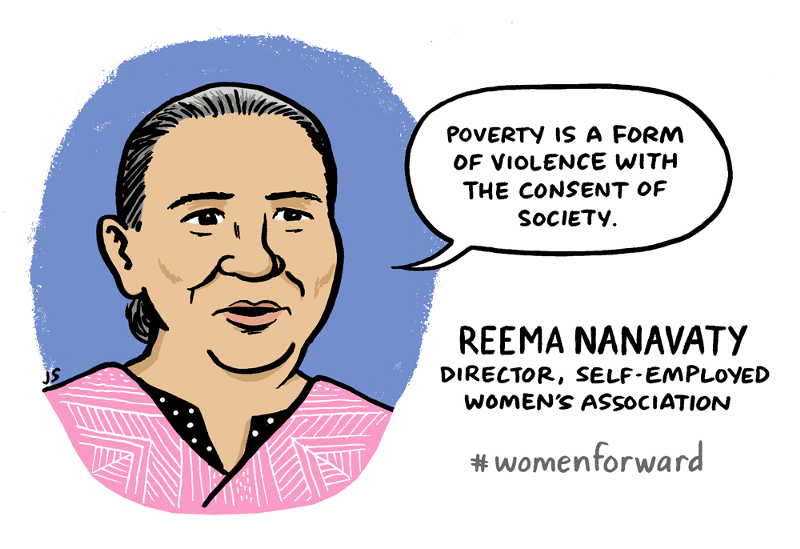

We believe it’s imperative that we study the organizations that have gotten the multi-issue movement really moving, especially on economic rights. Take the Self-Employed Women’s Association(SEWA), which has created large-scale change at the intersections of labor rights, women’s empowerment, gender-based violence, and health for over four decades. Of the female labor force in India, more than 94 percent of women are in what’s called “the unorganized sector.” Recognizing the dire need for education and empowerment among this population, SEWA has done everything from targeting sexual and economic exploitation, to creating childcare co-ops, to setting up literacy programs. SEWA is proof that grassroots can inform the treetops; it has been globally recognized and held out as a model to be replicated elsewhere.

Another great example, this one born stateside, is the National Domestic Worker’s Alliance (NDWA). Founded in 2007, NDWA has done revelatory work both making visible and fighting for the rights of domestic workers in 36 cities and 17 states. There are at least 1.8 million such workers—such as nannies, elder caregivers, and housecleaners—in America, and the number is only expected to rise. Rather than relying on traditional labor organizing tactics of collective bargaining against a single employer, they’ve often had to get creative about how they engage both workers and their employers — many of whom are mothers, fathers, daughters, and sons with obvious incentives to make the critical caretaking work that domestic workers do a dignified experience. NDWA has gotten Domestic Workers Bill of Rights on the books in six states and counting, and they won a landmark victory when the Department of Labor released new regulations to cover homecare workers under federal minimum wage and overtime protections nationwide. But even more interesting, their efforts touch on a huge range of issues — economic rights, to be sure — but also immigration, racial justice, the feminization of the caring professions, and the growing elderly population, among so many more.

Sometimes it’s not an organization, but a movement, that demonstrates just how effective, not just enlightened, multi-issue efforts can be. Black Lives Matter — which has exploded onto America’s streets and consciousness over the last two years — was started by three self-described black, queer women. Despite the fact that the mainstream media has sometimes painted it as a narrowly focused fight only interested in protesting police violence, the vision and tactics employed by this decentralized network have been vast. Black Lives Matters chapters have tackled everything from affordable housing to criminal justice to media representation.

Interestingly, Alicia Garza — one of the founders — cut her teeth at the NDWA, where she still works. She will be joining Reema Nanavaty of SEWA, among so many other innovative leaders, to help us launch a new series at the Aspen Institute today called Aspen Forum on Women and Girls: Conversations Across Generations. In it, many of the world’s foremost experts on critical issues facing women and girls, particularly economic, will come together across differences and share solutions.

Three decades ago, University of California, Los Angeles, and Columbia University law professor Kimberle Crenshaw coined the term “intersectionality” to describe the multi-issue quality of the women’s movement. In brief, intersectionality is the idea that just as identities are intertwined (Crenshaw herself is both African American and female, an academic and activist, for example), so must our understanding of institutions of oppression be intertwined. This fall, she wrote with great urgency about how the term has become part of our everyday lexicon, but that it doesn’t always lead to the kind of enlightened action that we might hope for:

“Intersectionality alone cannot bring invisible bodies into view. Mere words won’t change the way that some people — the less-visible members of political constituencies — must continue to wait for leaders, decision-makers and others to see their struggles.”

What makes us most hopeful is that the historically invisible no longer seem to be waiting. A wide range of impatient, courageous rabble rousers, both globally and here in the US, are becoming un-ignorable — even to the notoriously myopic mainstream media. There’s never been such an exciting time for women of different generations to come together at the intersections and on the frontlines of the key issues of our times. See you there!

PEGGY CLARK is the vice president of policy programs, executive director of the Aspen Institute Global Health and Development Program, and director of the Alliance for Artisan Enterprise at the Aspen Institute. ANNE MOSLE is a vice president at the Aspen Institute and executive director of Ascend at the Aspen Institute.