“Notice they built two turns as you enter. Radiation doesn’t turn corners, so they designed it specially this way.” That’s Jack Covert, our guide on a tour of the fallout shelter constructed at the direction of Arthur Houghton on the Wye River property that is now the Aspen Institute’s Eastern Shore Maryland campus. Covert remembers being told this in 1962, at the height of the Cold War, when as a recent college graduate, he started doing grounds-keeping and maintenance at the Houghton property. It was the run-up to the Cuban missile crisis, Covert says, and he absorbed this bit of information along with details on maintaining the newly opened shelter—all of it “scary.”

The Cold War. It is a distant memory for those of us who were already born, distant history to those who were not. Yellow and black civil-defense signs in the halls of apartment buildings. Hushed adult conversations during the Cuban missile crisis. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists’ Doomsday Clock set at two minutes to midnight. But it’s back. A recent New Yorker article detailed the lavish preparations being made by some Silicon Valley billionaires for the end of civilization as we know it. Kim Jung-un threatens to unleash nuclear terror on the American mainland and our Korean Peninsula allies; our current president retorts with equally bellicose and unrealistic threats.

On the Eastern Shore of Maryland, surrounded by fields of corn and soybeans, Angus cattle roam and waterbirds drift overhead, and a remnant remains of an earlier era when the threat of nuclear apocalypse was as real as that little toolshed sitting there on the side of the road.

A casual visitor can easily miss the entrance to the 10,000-square-foot underground complex—it looks like a toolshed, a few hundred feet from the residence Arthur Houghton built for his family on the same parcel where the family of William Paca, a Maryland governor and signer of the Declaration of Independence, had lived.

A field of soybeans partially obscures the view to the approach road to the Institute’s River House, the house that Houghton began as a second home and that was completed as a conference center in 1988.

“It’s like a time capsule,” a visitor remarks as we make our way down the sloping entryway.

The place has a grim logic. Houghton, who was deeply engaged in the design and construction of all the properties at Wye, designed the shelter to house 50 people—not just him and his family but also all the staff he employed and their families as well. Howard Ely, a local builder, did the construction, pouring concrete on top of metal overlaid by five feet of earth.

No detail was unconsidered. There were showers, a printed-out protocol for decontamination, and bathrobes to change into afterward. Fresh sheets were ready, and each family was asked to bring a suitcase to store in the facility in advance, in case they should need to evacuate quickly to the underground dwelling. Years after bringing down a suitcase to provision his own loved ones, Covert opened it to find a pair of one of his children’s long since outgrown shoes.

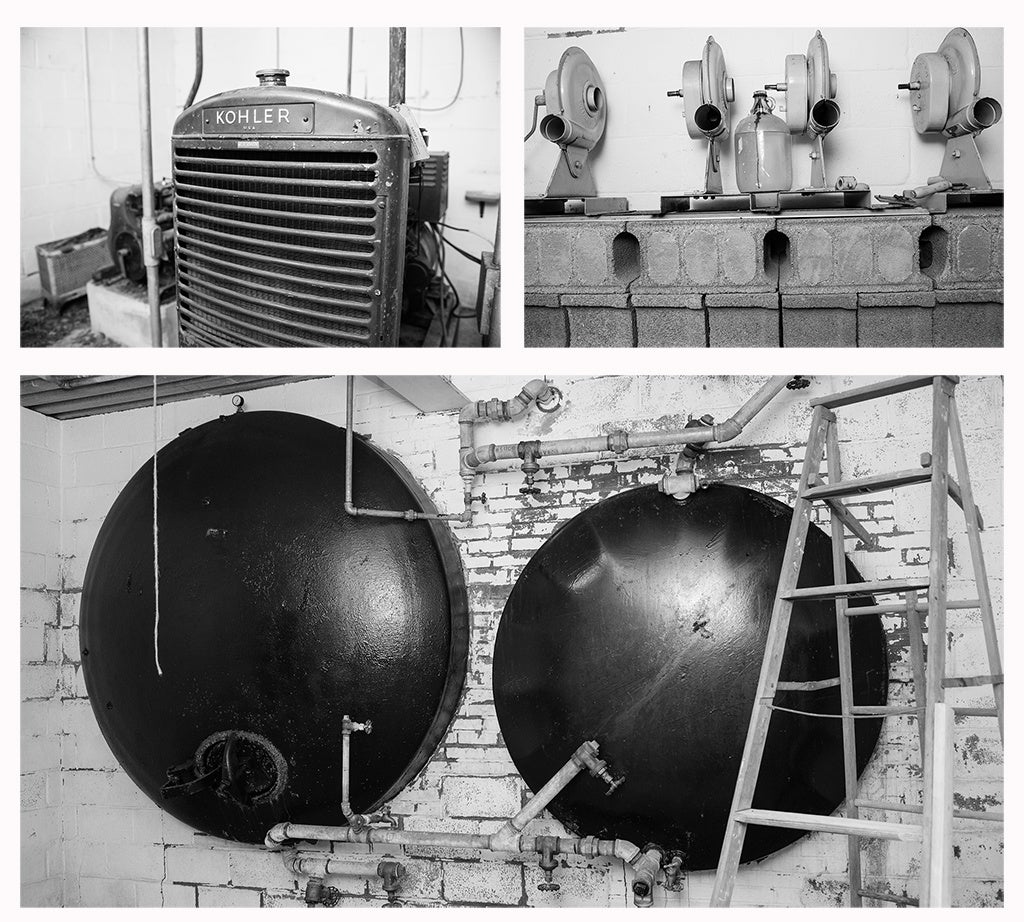

Rows of canned and dried goods took up one large storeroom, with Houghton’s directions for rotating and discarding outdated items written out in detail. Chemical toilets were designed to save precious water. Generators were housed in one “clean” area where they could be maintained and fueled, to be vented into another “dirty” one: radiation was inevitable in a space open to the outside air. Two water tanks held about 5,000 gallons between them—but were divided so that a leak in one would leave the second available for use. Air vents could be operated in two ways: by the generators and, if those failed, by hand crank, with sturdy hardware that still works, as Covert demonstrates for us. Bunk beds, gone since the shelter became a storage facility for Institute archives, furnished each room, with a special suite designated for the owners—the chintz fabric of an ancient settee and an upholstered screen hint at the ambience. There was even a stack of body bags in a remote corner.

Houghton stocked the shelter with tools and lumber as well, so that “the men could build something if they needed it,” Covert explains. Fishing tackle and guns for hunting would allow survivors, once they emerged, to provide food for their families. It was said that Holly Houghton, Arthur’s daughter, claimed she would not go into the shelter in the event of calamity, for she could not bring with her a beloved horse. And the Houghton family was not alone in its preoccupation.

Fallout shelters were in vogue on the Eastern Shore in the 1960s, says Jeff Horstman, Arthur’s stepson. Though few, if any, were as elaborate as this one, even modest homes had basement shelters stocked with a few basics and water, designed to let their residents ride out nuclear Armageddon. The Eastern Shore was, after all, just far enough from DC to be out of what was certain to be a blast zone. Survival, the experts told locals, was possible with the right precautions. The worldly and well-connected Houghton knew people in Washington; he’d get advance notice if things were falling apart. As Covert remembers his words, wouldn’t it be foolish not to have built the thing if it turned out to be needed?

By the late 1970s, the concept and reality of “mutually assured destruction” seemed to make that prospect more distant—although tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union remained high well into the Reagan years. Horstman remembers the shelter as a great place for his teenage parties, and a curiosity that stimulated cocktailparty banter among visitors—excursions to view it were common after a few drinks on the patio. Princess Anne and Mark Phillips were among the dignitaries who toured it as houseguests of the Houghtons. By the time the Wye River property was donated to the Institute in 1979, the fallout shelter had fallen into disuse. A recent visit revealed rows of files from Institute programs in place of the cannedgoods inventory, and rooms of teleprompters and recording equipment—relics of a period when several rooms were used to store items from the collection of the former Museum of Broadcasting, now the Paley Center for Media in New York City. One script on roller paper in enormous early computer script reads:

“I’ll give you one more chance to get that beam going

or I’ll kill you and the girl and I’ll rule the moon with this

gun—One—

Save Yourself Jerry!

Two—

No!

Three—”

In a recent article in Wired, my Institute colleague Garrett Graff notes that at one time, the Federal Emergency Management Agency inventoried properties that could be used to shelter public officials in an emergency. Perhaps it is time to dust off the Wye fallout shelter and put it back on the list. We can hope not.

Meryl Chertoff, the executive director of the Institute’s Justice and Society Program, worked for the Federal Emergency Management Agency from 2003 to 2005.