The pursuit of economic opportunity for all Americans is as important to the health of the country’s economy as it is to the strength of its democracy. The promise that hard work and determination will yield economic success is a central American ideal, but it has been called into question as secular economic forces and institutional changes have reshaped the American economy and had an uneven impact on Americans’ ability to prosper.

Economic prosperity is increasingly a function of an individual’s education level, where they live, and the income quintile into which they were born. Expanding economic opportunity to more Americans will mean breaking down barriers to success and fostering more widespread opportunity. It will also mean investing in pathways for individuals to develop valuable skills, enhance their earning potential, and pursue meaningful work.

Large differences in economic outcomes persist among workers with and without a college education. While highly skilled workers are thriving, enjoying high wages and strong demand for their advanced skills and education, workers without a college degree have experienced stagnant or declining wages and reduced employment. Prime-age men are working at lower rates today than at any point in the post-war era, driven primarily by reductions in the rate of work among non-college educated individuals.

Geographic disparities in economic opportunity have become more pronounced. As prosperity is increasingly concentrated in certain cities and regions, other communities, particularly those in rural areas, falter. Regional differences in household incomes, along with many other economic outcomes, are no longer converging as they have historically. Artificial constraints on housing supply in the most economically productive regions have driven up housing costs, making these areas less accessible to potential in-movers and, in turn, stifling geographic mobility and economic convergence.

In light of these challenges, The Aspen Economic Strategy Group (AESG) invited leading scholars from across the country to present innovative, evidence-based, and bipartisan policy ideas to address salient barriers to economic opportunity. The discussion papers and memos presented in this volume are arranged by three policy goals: (1) developing human capital for the modern, global economy; (2) increasing prime-age labor force participation; and (3) promoting private sector job creation and wage growth.

A cornerstone of the AESG is promoting bipartisanship in economic policymaking. To this end, each of the three discussion papers in this volume is co-authored by AESG members who have served as senior counselors to past Democratic and Republican presidential administrations. These discussion papers are the product of a bipartisan working group process explained in a preamble to this volume. Glenn Hubbard and Austan Goolsbee propose new evidence-based investments in America’s community colleges, at a similar scale to the 19th century Morrill Land Grant Program. Keith Hennessey and Bruce Reed discuss the challenges of low prime-age labor force participation and potential policy responses. Phillip Swagel and Jason Furman discuss the macroeconomic policies that best promote growth and present two policy options to incite wage growth among low- and middle- income workers. The volume also includes nine commissioned policy memos from outside experts, each of which addresses a specific policy challenge related to at least one of the three policy goals.

Policy Goal 1: Building Human Capital for the Modern, Global Economy

A policy agenda to build human capital for the modern, global economy would include investments in education at all levels and ages, including early-childhood, kindergarten through grade 12, post-secondary, and mid-and continuing career. Many thoughtful and careful scholars, policy advocates, and experts have weighed in elsewhere on the need for early childhood and K-12 investments and reforms. In this volume, we focus on the need for skill development beyond high school. This decision was a practical one, made to keep our volume focused, not because earlier investments aren’t critically important. With that caveat in mind, we stipulate that even a post-secondary agenda to build human capital would need to be multi-faceted. There is a need to increase the number of Americans with a college degree, to provide meaningful alternatives to college, and to create opportunities for dedicated skill development throughout a worker’s career.

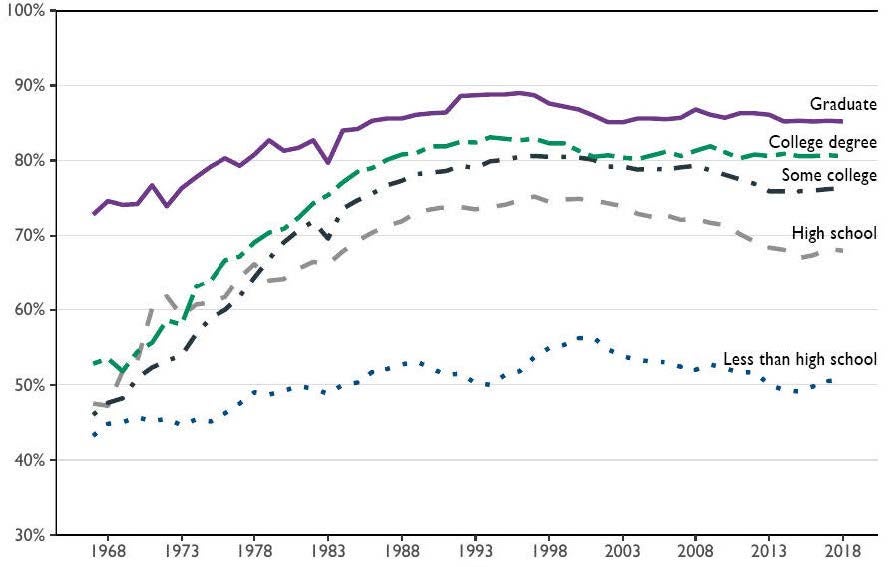

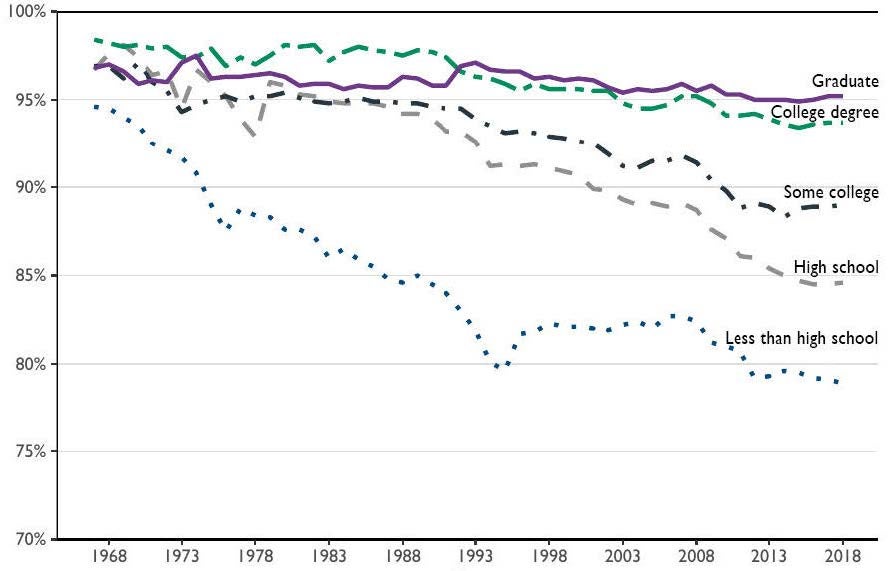

The modern economy greatly favors college-educated workers. Employment rates among those without a college degree have fallen substantially in recent decades. Prime-age men used to participate in the labor force in roughly equal measure across education groups. That is no longer the case. A 2016 Council of Economic Advisers report notes that in 1964, 98% of prime-age men with a college degree or more participated in the workforce, compared to 97% of men with a high school degree or less. In 2015, the participation rate for college-educated men had fallen only slightly to 94%, while the rate for men with a high school degree or less had dropped precipitously to 83%. Since the early 1990s, the labor force participation of prime-age women has also fallen by much more among those without a college degree. In 2016, the labor force participation rate among prime-age women with a bachelor’s degree or higher was 87%, as compared to 62% for those with a high school degree or less.

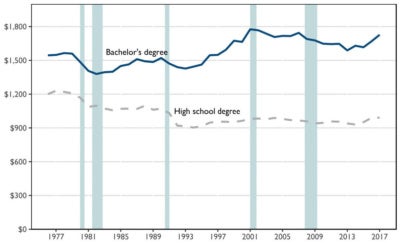

In addition to growing gaps in employment rates, there are large earnings gaps between those with and without a college degree. In 2017, workers with a college degree earned nearly two thirds more than workers without a college degree. As Figure 1 demonstrates, the earnings gap in weekly earnings between workers with a college degree and those with a high school degree increased substantially in the latter half of the 20th century, and that gap remains large. Increasing the number of Americans with a college degree would advance both individual economic security and the productivity and competitiveness of the American economy more broadly.

Figure 1. Real Weekly Earnings by Education Level,

1975 – 2017

The sample includes full-time workers between the ages of 25-64. We include workers with a high school diploma or equivalent degree in the shaded series.

In recent decades, rates of college enrollment in the U.S. has increased steadily. However, college completion rates remain low. Among young adults age 25 to 34, only about 26% have a bachelor’s degree. National data on students who enrolled in college in 2010 reveal the extent of the so-called college drop-out problem. Among students who initially matriculated at a four-year institution, nearly half failed to complete their degree within six years. Among students who initially enrolled full-time at a two-year public institution, nearly 42% had not received any degree or were no longer enrolled in school six-years later. Among students from two-year colleges who successfully transferred to a four-year institution, only 40% completed a bachelor’s degree within six years. Increasing the rates of persistence and completion among college students would have a significant impact on their earnings potential, and, more broadly, would increase the skill level of the U.S. workforce.

Achieving higher rates of college completion among young adults is necessary but not sufficient. Those without college degrees cannot be relegated to low-paying jobs and limited opportunities. Alternative pathways to economic prosperity are needed such that those without college degrees can still meaningfully develop their talents and contribute productively to the modern economy.

Furthermore, the skills demanded in the modern economy constantly evolve. Workers transition jobs and industries multiple times throughout their working years and, even within an occupation, tasks change. Individuals must adapt to new technologies, learn new skills, and earn new credentials over the course of their careers. This paradigm shift necessitates new models of training and skill development that are better suited to the needs of full-time, working adults. While the education marketplace has already begun to adapt to these new realities, many public institutions are lagging behind due to resource constraints.

In their discussion paper in this volume, AESG members Glenn Hubbard and Austan Goolsbee call for new investments in America’s system of community colleges at a similar scale as the 19th-century Morrill Land Grant Acts. Community colleges offer widely accessible and flexible postsecondary education and mid-career training opportunities. Yet, despite their promise and potential, community colleges suffer intense resource pressures, which constrain the educational and labor market outcomes of their students. Hubbard and Goolsbee propose a new federal grant program that provides funding to community colleges, contingent upon institutional outcomes. Additionally, they call for seven complementary proposals to further expand opportunities for mid-career skill development and training and to provide better pathways into the workforce for non-college-educated workers.

Work-based training opportunities, particularly apprenticeships, are less common in the U.S. labor market compared to other advanced economies. In a policy memo in this volume, author Robert Lerman proposes enlarging apprenticeship programs in the United States and argues that such a move would increase youth employment and wages. His proposal calls for the development of occupational standards, credible end-point assessments, and independent certifying bodies to support high-quality apprenticeship programming. Lerman also advocates for a robust marketing effort to reduce labor market stigmas that are sometimes associated with work-based training.

Career and technical education (CTE)—a combination of career-specific training and other traditional academic content—is another important pathway for individuals to gain career-ready skills outside of traditional four-year degree programs. However, not all programs are created equal, and there is an especially significant disparity between CTE program outcomes across public and for-profit institutions. The policy memo by author Ann Huff Stevens clarifies the existing evidence about “what works” in career and technical education and proposes several reforms to strengthen evidence-based programming.

There is a great deal of optimism about the potential for online learning to drastically expand access to high quality skill development due to its flexibility and cost-effectiveness. However, author Joshua Goodman’s policy memo cautions that not all students are served equally well by online educational programming. Academically at-risk students typically perform worse online than they do in traditional in-person settings. Goodman’s memo serves as an instructive primer to policymakers who are considering plans to leverage online education for economically vulnerable mid-career Americans.

Policy Goal 2: Expanding Labor Force Participation

The U.S. labor force participation rate—the share of working-age individuals employed or looking for work—reached an all-time high of 67% in 1999 and has since declined by nearly five percentage points. This steady decline has coincided with several trends, some cyclical, such as protracted unemployment following the Great Recession; some demographic, such as population aging and the retirement of the Baby Boomer generation; and some structural, such as changes in the demand for certain types of skills or workers.

Prime-age workers (age 25-54) are the backbone of the U.S. labor force. Thus, declines in the labor force participation rate among this group have troubling implications for the future of U.S. economic growth and widespread prosperity. The prime-age labor force participation rate today remains two percentage points below its 1999 peak of 84%. If it had held steady at its peak, there would be an estimated 2.4 million more prime-age workers in the labor force today. Periods of non-employment during prime-earning years can lead to lower future earnings, as workers lose valuable opportunities to gain experience and to build workplace skills.

Declining prime-age labor force participation has been most pronounced among workers with lower levels of education, as shown in Figure 2. That gap in employment between those with and without a college degree has grown by nearly ten percentage points since the 1960s among both men and women. Today, one in five working age men and one in two working age women without a high school diploma are not in the labor force.

Figure 2. Male and Female Prime-Age (25-54) Labor Force Participation,

1968-2017

Men

Women

Note: Individuals were considered in the labor force if they reported they were at work; held a job but were temporarily absent from work due to factors like vacation or illness; were seeking work; or were temporarily laid off from a job during the preceding week of the survey.

In their discussion paper, AESG members Keith Hennessey and Bruce Reed review the many potential explanations for the decline in labor force participation among prime-working age individuals. Drawing on the work of Abraham and Kearney (2018), they observe that demand-side factors such as globalization and technological change have depressed demand for low-skill workers, but, this fact alone cannot sufficiently explain the overall decline in labor force participation. Hennessey and Reed point to additional supply-side considerations, such as the rise in disability insurance rolls, which may be discouraging workers from re-entering the labor force after a period of unemployment. They also call for additional research to better understand why labor force participation in the United States is lower than that of other advanced economies.

This section of the volume also includes two policy memos. A memo written by James Ziliak highlights the rural/urban divide in employment rates and economic prosperity. Ziliak provides a thorough review of wage and employment trends across non-metropolitan areas, showing that less-educated, rural workers are further behind their urban counterparts today than they were fifty years ago. Ziliak also puts forward a set of proposals to address rural employment challenges, arguing for both people-based and place-based policy approaches. People-based approaches include relocation assistance, as well as a short-term credit to subsidize commuting expenses. Place-based programs include investments in rural broadband, the expanded small business loans and grants to rural entrepreneurs, and a federal jobs program to revitalize rural infrastructure.

In a second policy memo in this section, authors Gordon Dahl, Manudeep Bhuller, and Katrine Løken address the role of incarceration in limiting employment opportunities and call for prison reform as an economic strategy. In particular, many observers have noted the link between high rates of incarceration and low rates of employment among less educated African American men in the United States. Dahl, Bhuller, and Løken argue the U.S. is missing out on an opportunity to promote employment and build skills among incarcerated populations, which could help improve labor force attachment when formerly incarcerated individuals re-enter society. Drawing upon rigorous evaluations of Norway’s prison system, the authors propose shortening prison sentence lengths, investing in education and training programs, and expanding post-release programs to support reentry into society.

Policy Goal 3: Increasing Private Sector Wages and Jobs

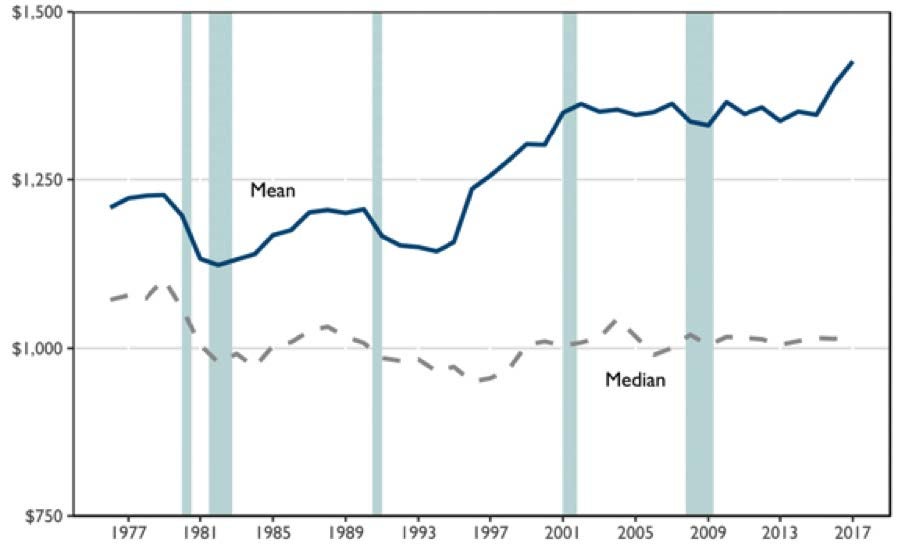

In the three decades following the end of World War II, the income of a typical American household grew by roughly 3% per year. Since the 1970s, low- and middle- income American households have experienced income gains of only one percent per year. Figure 3 compares mean and median weekly earnings since the late 1970s. Median earnings have been stagnant since the early 1980s, while mean weekly earnings have grown slightly more, reflecting that wage growth has been concentrated at the upper end of the income distribution.

Figure 3. Average vs. Median Weekly Earnings, 1976-2017

Note: Sample includes full-time workers (defined as those who worked more than 2080 hours in a year) between ages 25-64.

Slow wage growth has coincided with slower overall economic growth and, perhaps most importantly, lower productivity growth. The average annual productivity growth rate since the 1970s has been half that of the preceding postwar period.

Understanding the link between productivity and wages is critical to understanding recent wage trends. We thus commissioned two memos on this topic from leading experts. Some recent observers have argued that the link between wages and productivity has weakened, due in large part to diminished bargaining power among workers and increased wage setting power of firms. In his policy memo, author Michael Strain argues that the link between productivity and wages remains strong.

In another memo in this volume, author Chad Syverson observes that wages among workers at the lower end of the wage distribution have even fallen behind the more languid overall growth target. The widening chasm between the upper and lower portions of the wage growth distribution has coincided with larger gaps in productivity growth between firms, which may reflect two different sides of the same coin. Syverson reviews existing explanations for slower growth of productivity and wages, as well as increased dispersion. He concludes that it is impossible to tell, from current existing evidence, whether these trends are the result of increased market power and rent-seeking or of more benign explanations unrelated to market power, such as a breakdown in the diffusion of best practices, and technologies across firms in the marketplace. He then describes potential policy responses to the slowdown in productivity growth: investing in infrastructure, improving managerial practices, encouraging competitive product markets, and reducing frictions in the input markets of labor, capital, and ideas.

In their discussion paper, AESG members Jason Furman and Phillip Swagel discuss the macro conditions necessary for wage and job growth to occur in the long run and outline a broad bipartisan policy agenda for creating such an environment. The goals of this agenda include: (1) Ensuring the economy is operating at full employment; (2) Increasing long-term productivity and labor force growth; (3) Making a more resilient economy in the face of shocks and inevitable cyclical downturns; (4) Ensuring more sustainable economic growth over the longer term; and (5) Contributing to more broadly-shared prosperity. The authors offer a number of policy approaches to achieve these goals.

Based on their decades of combined economic policy experience, Furman and Swagel acknowledge the political difficulties inherent in designing specific policies to achieve these goals. They thus turn their attention to policy options that more directly target the take-home pay of low-income workers in the short-run. Taking the economic environment and skills as given, they outline two specific alternative policy options for raising the take-home pay of less skilled workers during the course of a business cycle. The first option expands on the existing Earned Income Tax Credit structure to nearly triple the amount that goes to workers without qualifying children. The second option sets up a new structure to deliver wage subsidies to low-income workers, which would be administered through employers.

The wage subsidy proposal in Furman and Swagel’s paper expands upon the policy memo written by author David Neumark. In his memo, Neumark proposes an employer tax credit to partially offset the cost of minimum wage increases for firms that employ low-wage workers. Taking future minimum wage increases as a given, Neumark’s Higher Wages Tax Credit (HWTC) would provide a tax credit of 50% of the difference between the prior minimum wage and the new minimum wage, for each hour of labor employed. This credit would reduce the incentive for employers to substitute away from low-skilled workers in the face of minimum wage increases, thus mitigating the potential adverse effects of minimum wage increases while simultaneously preserving and possibly enhancing some of the benefits of minimum wage hikes.

This section of the volume also includes a policy memo by author Joshua Gottlieb on the issue of housing prices in high productivity cities. Gottlieb examines the indirect role that housing supply constraints might have on productivity and wage growth by restricting the flow of human capital. Zoning restrictions are estimated to constrain economic production and wages by more than two trillion dollars per year (Glaeser and Gottlieb, 2009) and are often most punitive for low- and middle-income households because they drive up the cost of housing for potential in-movers. Gottlieb proposes to overcome the NIMBY (“not-in-my-backyard”) phenomenon by encouraging state governments to enact minimum zoning mandates that would preempt local land use restrictions that artificially reduce urban density.

Conclusion

The papers and proposals contained in this volume target specific barriers to economic opportunity for many American workers. They are actionable and evidence-based. We do not pretend to think that any of the policy proposals contained in this volume are the “silver bullet” solution to the challenges outlined in our introductory paragraphs. Yet, the collection of ideas offered in this volume offer policymakers a thoughtful starting place in addressing a critical set of current challenges.

Furthermore, the policy agendas outlined in the three discussion papers contained in this volume have bipartisan appeal. Each discussion paper reflects the joint work of prominent economic policy experts. The discussion papers were informed by the collective contributions of bipartisan working groups and were drafted by a pair of leading experts who served as senior economic counselors in past Democratic and Republican presidential administrations. The authors of these discussion papers united around a common set of facts and worked together to identify specific solutions. We hope this volume serves as a reminder to its readers that bipartisan solutions exist, and that there are ample opportunities to come together to identify and implement them.