Two Steps at a Time

For first-generation students, getting into college can be the biggest challenge of their lives. And the hard part comes next.

It was Joel Baraka’s first day of college, and he had a plan.

The University of Wisconsin freshman had more challenges than a typical new student. He had gone to high school in South Africa and was originally from Uganda — almost as far away from Madison, Wisconsin as you can get. His parents had not gone to college, so he moved across the globe without really knowing what to expect.

The culture, the weather, the sometimes-Kafkaesque systems of financial aid and academic planning — these were out of his control. So he concentrated on what he thought he could control. “Get to class before the professor,” he would tell himself. “And sit in front, where you learn better.”

The morning of his first class, he found the building with ease and entered with time to spare. But inside it felt like a labyrinth. He wandered for 30 minutes trying to find the classroom, eventually staggering in late while the rest of the students watched. He had to sit in the back.

I ended up spending 30 minutes trying to find the actual room, I was so tired I actually almost went back home.”

“After the class was over, I was really devastated,” he says. “It was like I had failed. This was the start of my journey and I hadn’t been able to meet what I had planned to do.”

Baraka is far from the only student to have a disastrous first day of school — the best laid plans of mice and freshmen often go awry. But as a first-generation student, his challenges are greater than those of many of his peers. And without family guidance and inherent expectations of higher education, students like him face a far greater risk of dropping out of college before earning a degree. It’s a problem that initiatives at the Aspen Institute, together with educators and colleges across the nation, are working to solve.

Access across America

Where the Aspen Institute is helping students get higher education

Legend

Click items in the legend to filter by Aspen initiative

Defining “first-generation” can be a thorny prospect when college students come from such a diversity of backgrounds and familial situations. While the Higher Education Act keeps the designation relatively simple — any student whose parents (or parent) did not complete a baccalaureate degree — researchers, colleges, and nonprofits can have tighter or looser definitions. Whatever the specifics, it’s a term meant to refer to students who go to college despite not having a family history of higher education, often with low-income and/or immigrant backgrounds.

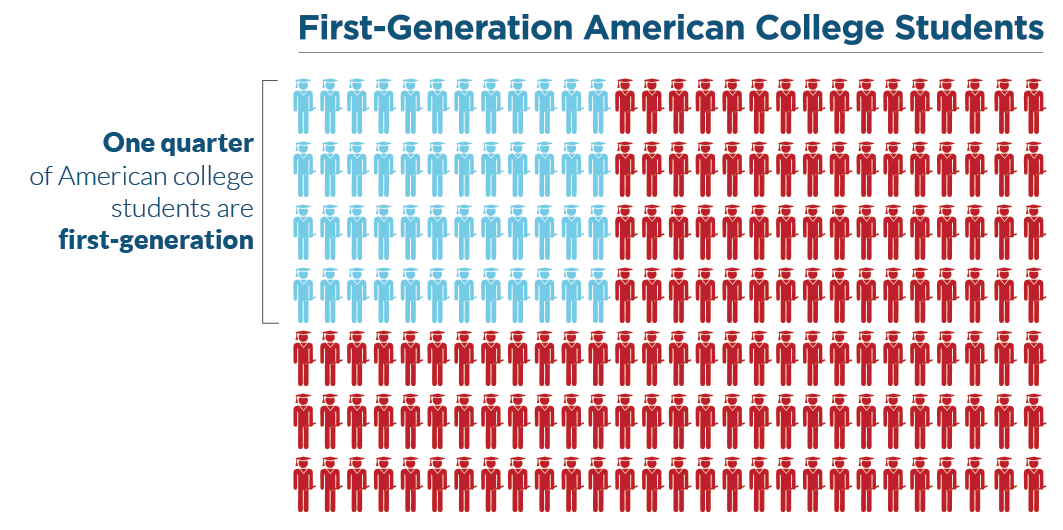

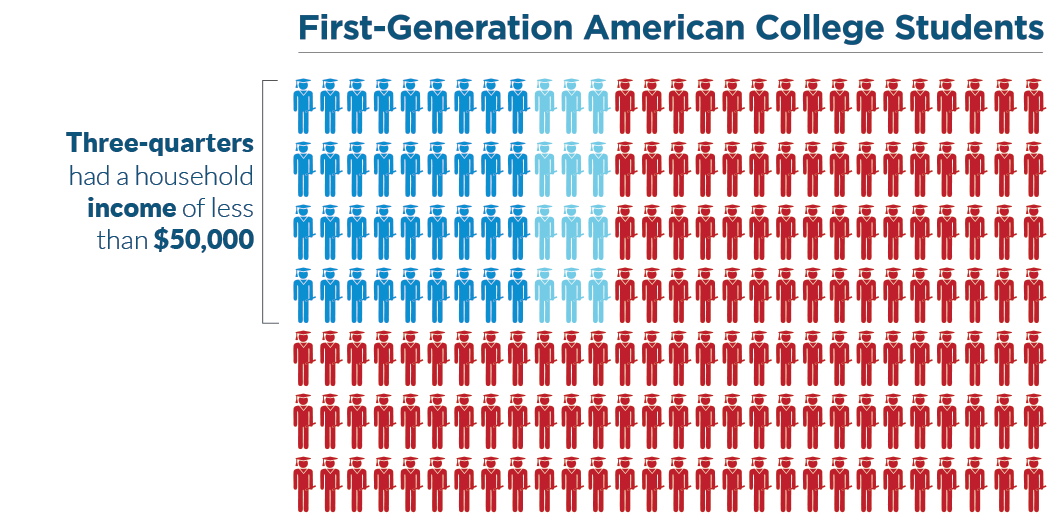

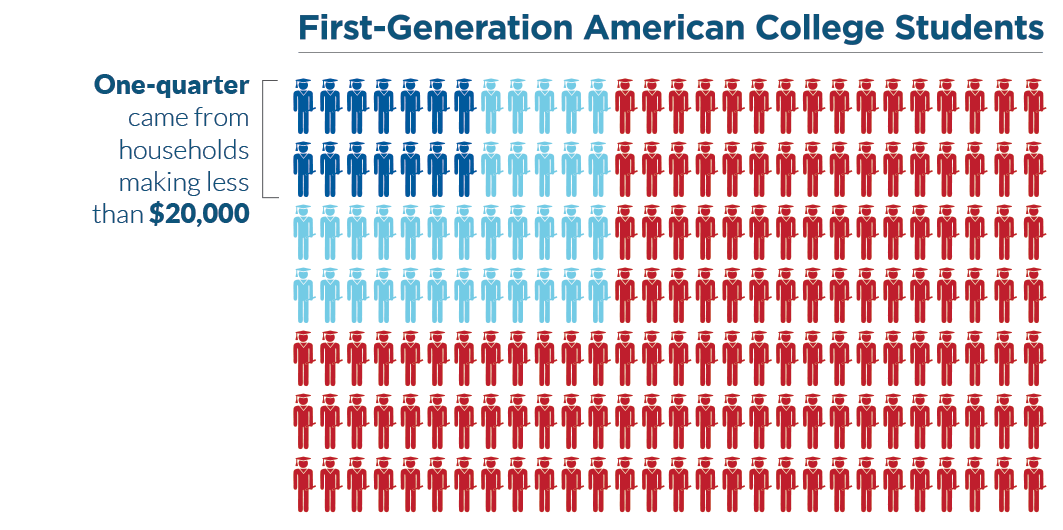

About a quarter of American college students are first-generation, according to a 2017 report from the US Department of Education. Three-quarters of first-generation students had a household income of less than $50,000, and a quarter came from households making less than $20,000. These students are more likely to be black (14 percent compared to 11 percent for other students) and much more likely to be Latino (27 percent compared to 9 percent).

The study found that first-generation students had a much more difficult time completing college than students from a college-educated background. Just over half of first-gen learners earned a certificate or higher, compared to 70 percent of more traditional students. The difference is even starker when looking at those who completed a bachelor’s or higher — just 23 percent of first-generation students, compared to 55 percent of others.

Helping first-generation students graduate is a process that begins well before college. The Aspen Institute’s Youth Programs work with young people ages 14-24 to help them excel academically and in their communities, bringing students together to create a network that can aid them in their application process and beyond. This includes the Aspen Young Leaders Fellowship, a two-year program in which young leaders are selected to participate in dialogues and create change in their communities, and the Bezos Scholars Program, of which Joel Baraka is a part.

Claudia Saavedra, an Aspen Young Leaders Fellow, graduated summa cum laude from Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey and is on track for a master’s degree next year. Getting to that point, though, was a struggle.

“My parents spoke very little English, they just have a high school degree from another country,” she says. “They just didn’t know how to navigate the education system. I didn’t know what financial aid was. I didn’t know what a FAFSA was.”

Saavedra wasn’t able to afford four-year college initially, but got her start at County College of Morris.

“My biggest challenge was the college application process — I knew that I wanted to go to college but I didn’t know how to get there,” she says. “Attending community college actually helped me with my transition.”

Many colleges have wised up to the challenges these students are facing. The Common Application now allows students to identify as first-generation, which has allowed schools to offer preferred admission, waive application fees, and keep data on how many first-gen students are coming to campus. While that has changed the admissions landscape completely, it takes more than an acceptance letter to help students earn their diplomas.

First-generation students can struggle with thousands of little things once they get to campus, things that students from a college-educated background might take for granted. Joel Baraka found himself still getting used to using a computer regularly while professors communicated over email and assigned almost everything digitally. “It’s as simple as typing on a laptop,” he says. “I get surprised when the US students are typing. They are so fast!”

And as Baraka found out his first day of school, the pressure of success can be a huge emotional burden. Frosilda Pushani, a sophomore at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, knew how much her family was counting on her.

“I remember I would cry literally every night because I thought I couldn’t handle one of my Spanish classes,” she says. “I know I have to work harder than everyone else to achieve the goals I want because I don’t have a backup plan.”

Baraka knows that the more traditional students around him are also working hard and stressed out, but it’s hard for him to explain the greater challenges he’s facing. “I have to understand culture, and then technology, and then academics,” he says. “It’s like they are taking one step where I have to take two steps.”

The Aspen Institute College Excellence Program works with schools across the country to identify and implement policies that will help students like Pushani, Saavedra, and Baraka learn, graduate, and eventually find a job. “To educate students who are the first in their families to attend college, colleges have to do more than simply open their doors,” says program founder and executive director Josh Wyner. “They need to actively address the challenges that these students face, from managing financial hardships to understanding educational choices to thoughtfully preparing for life after college.”

As they track the experiences of first-generation students more closely, schools are taking notice. The American Talent Initiative, part of the College Excellence Program in collaboration with Ithaka S+R and Bloomberg Philanthropies, is a partnership between 100 colleges aiming to get 50,000 more low-income students on track to graduate by 2025. To do that, participating schools are adding services for the students who need to take two steps when others take one.

“If we believe that education really is access to opportunity, it has to be reaching every kind of student,” says Pomona College President G. Gabrielle Starr, whose school is a part of the American Talent Initiative. “It needs to be an engine of prosperity for an entire family. You can only be first-generation once.”

During new student orientation, Pomona hosts a dinner for first-generation students and their families, which Starr says is important for helping ease the worries of parents sending their children off somewhere wholly unfamiliar. Once school begins, students are matched with faculty members who were the first in their own families to attend college, providing mentorship and making themselves available to answer questions. First-gen students on campus have also developed their own community to help others transition.

“There are first-generation college students everywhere” on campus, Starr says. “It really provides an air of possibility.”

Aspen Institute President Dan Porterfield saw that possibility firsthand. One-fifth of the class of 2021 at Franklin & Marshall College, where he served as president before taking over the Institute this past June, is first-generation. The class is also 20 percent Pell grant recipients and 27 percent US students of color, up from 5 percent and 11 percent a decade before.

“First-generation college-goers are among the most important Americans,” he says. “It’s critical that colleges recruit first-gen college students from all communities in every ZIP code. There’s talent in every corner of this country, and our colleges can and must do a better job at finding, funding, educating, and launching first-generation college students.”

That begins with meeting students’ full financial needs, but as students and faculty have experienced at Pomona, it certainly doesn’t end there. After schools actively recruit first-generation students, Porterfield says, they should bring them together once they’re on campus so they can learn from one another. Programs connecting new students with faculty, staff, and upperclassmen can provide practical advice on everything from course selection to internships and pre-professional development. And when those first-gen students find success, schools should shout it from the rooftops.

“It’s very valuable when a college president and her leadership team identify first-generation students as a critical asset to the school’s overall success and constantly reinforce that message,” Porterfield says. “It’s a serious mistake to view first-gen students as simply a collection of challenges to be remediated rather than as a collection of talents to be developed.”

Franklin & Marshall and Pomona aren’t the only places helping students to band together. As a member of the Newark cohort of the Aspen Young Leaders Fellowship, Claudia Saavedra is creating a space in which local first-generation and low-income students will be matched with mentors who can help them figure out career aspirations and guide them through the college application process.

Educational Attainment as of 2012

First-Generation College Students

Continuing-Generation College Students

Hover over charts to see more information

- Some College

- Undergraduate Certificate

- Associate’s Degree

- Bachelor’s Degree

- Master’s Degree or Higher

“The Aspen Young Leaders Fellowship honestly made me feel like the world was mine,” Saavedra says. “It was like, wow, someone actually believed in me, that I can create change. That was something I didn’t have.”

Joel Baraka found that the Bezos Scholars Program, run by the Bezos Family Foundation and hosted by the Aspen Institute, helped him prepare for his college journey. He was one of five students from his high school selected to participate in the Aspen Ideas Festival in 2017. (It was his first-ever time in the US — “The first two days I could barely breathe, the altitude was too much.”) The program continued to help over the next year, assisting with his college applications and even providing a recommendation.

“They would tell us about the US culture,” he says. “It helped me so much in handling the application process.”

If we believe that education really is access to opportunity, it has to be reaching every kind of student, It’s an engine of prosperity for an entire family. You can only be first generation once.”

After he got into the University of Wisconsin, the Bezos Family Foundation sent Baraka books and games to help him relieve stress and checked in regularly. “I feel like I have family,” he says, “and someone to contact if I have any problems.”

Outside of occasionally forgetting he needs a hat when venturing out into the Wisconsin cold, Baraka has adapted to college life. He’s studying civil engineering and showing up to classes on time, if not early. But he knows there are many first-generation students or potential students who haven’t been afforded the same opportunities. With enough support from schools and organizations like the Aspen Institute, first-gen students won’t have to walk any farther than their peers to get their diplomas.