This issue brief has been updated from the May 2017 Worker Training Tax Credit issue brief to include economic modeling.

Summary

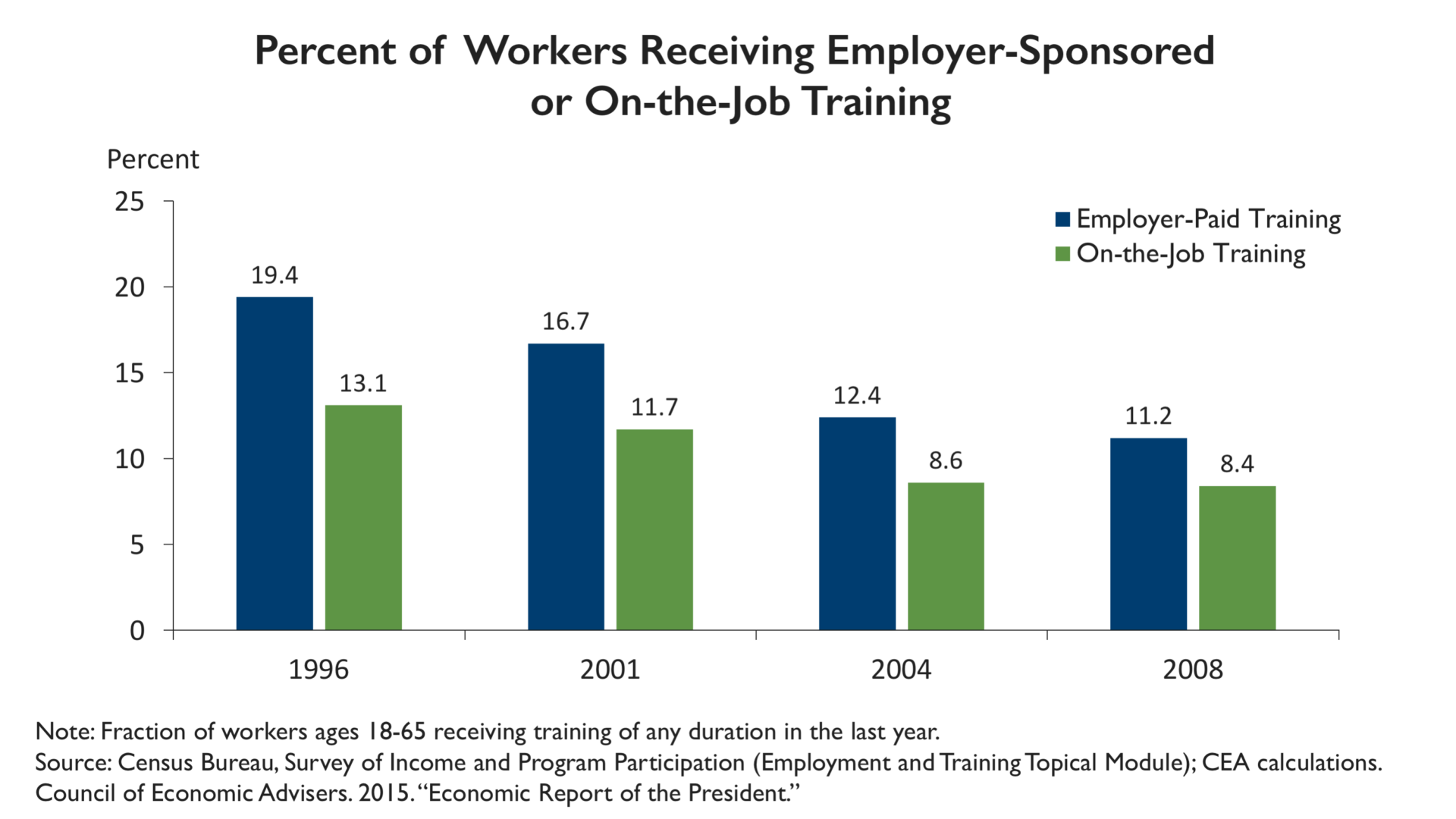

Rapid advances in technology, including artificial intelligence and automation, are transforming industries and reshaping the skills necessary to secure and keep a job. In response, U.S. workers will need to acquire skills that are not easily automated or that complement ever-changing technology. Yet, data suggest an alarming trend: there is a steady decline in the amount employers are investing in their workforce.[1]

Federal and state policymakers should consider using tax incentives to encourage additional workforce training investments. To accomplish this, in May 2017 the Future of Work Initiative proposed the Worker Training Tax Credit. Modeled on the popular Research and Development (R&D) Tax Credit, this new tax credit could be used by small and large businesses to invest in training for their low- and middle-income workers.

Based on economic modeling recently conducted by District Economics Group, the Worker Training Tax Credit would cost roughly $146.5 million over ten years, and lead businesses to increase training investments by 8.5 percent. Because the tax credit excludes training provided to high-income workers, these induced training investments would provide greater opportunity to low- and middle-income workers.

Background

The importance of investing in human capital, and its impact on economic growth, has been well documented. Investments in human capital improve worker productivity, spur innovation, and provide pathways for upward mobility.[2]

Investing in worker skills is becoming more important. As innovation and automation disrupt the economy, workers will need training to work with new technologies or to acquire skills necessary to transition to new jobs.[3] While four-year degrees continue to provide an earnings premium, other types of credentials also provide considerable economic returns.[4] In one study, vocational certificates and associate degrees corresponded to more than 30 percent higher earnings than a high school degree alone.[5] A World Economic Forum report found that by 2020, more than one third of the core skill sets of most occupations will be skills that are not considered crucial to today’s workforce.[6] In short, access to education and training opportunities over the course of workers’ careers should be a key public policy objective.

Some in the business community have recognized the need to increase investments to improve worker skills. Corporate leaders including JPMorgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon and IBM CEO Ginni Rometty, and former CEOs Jeffrey Immelt (General Electric) and Andrew Liveris (Dow Chemical), and have called for additional investments in worker training.[7] More than 20 companies and trade unions recently announced commitments to expand apprenticeship programs, retraining and continuing education opportunities.[8]

Despite these commitments, the available data suggest that businesses have been investing less in their workers, not more. From 1996 to 2008, the percentage of workers receiving employer-sponsored or on-the-job training fell 42 percent and 36 percent, respectively (see chart below).[9] This decline was widespread across industries, occupations, and demographic groups.[10]

While business investment in training has fallen, the public sector has not made up the difference. As a share of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), government spending on training and other programs to help workers navigate job transitions is now just 0.1 percent of GDP, lower than all other OECD countries except for Mexico and Chile, and less than half of what it was 30 years ago.[11]

In part, the decline in employer-provided training can be explained by changes in the employer-employee relationship over the past thirty years. A generation ago, when many employees worked at the same company for their entire career, an investment in worker training would benefit the worker and the company making the investment. Although measures vary, job tenure across most demographic groups has declined over the past thirty years, leading The Economist to note that “the single, stable career has gone the way of the Rolodex.”[12] [13] Fearing that workers will take their new skills to other employers, companies have responded over time by reducing their investments in training and skill development.

This trend exposes a market failure. Because the benefits of training reside primarily with the worker rather than with the business, there will always be a portion of the investment that benefits the overall economy but not the business itself. As relationships between workers and businesses become less stable, businesses have a more difficult time capturing the return on their training investments. The result is less investment in training at the same time as the economy requires a more highly-skilled workforce.[14] This underinvestment justifies public policies to make workforce investments less costly and more attractive to employers.

Moreover, many low- and middle-wage workers do not benefit from existing training investments because businesses disproportionately direct training expenditures to the highest-paid and highest-educated workers.[15] A report from the Hitachi Foundation explains that training investments are often managed as worker benefits, which are also skewed towards higher-paid workers.[16] This skewed distribution suggests that any policy solution to the training disinvestment problem should target low- and middle-wage workers.

Proposal: The Worker Training Tax Credit

To address the decline in employer-provided worker training, the Future of Work Initiative proposes a business tax credit to offset a portion of the cost of new training activities for non-highly compensated workers. The Worker Training Tax Credit would mirror the policy design of the popular R&D Tax Credit. Businesses would establish a base expenditure level for qualified training expenses, which would be determined by averaging the amounts spent in each of the three years prior to the current tax year.[17] The value of the tax credit would be 20 percent of the difference between the current year qualified training expenditure and the base expenditure level. The credit would only cover training for non-highly compensated workers (less than $120,000 per year), the standard currently used in the Internal Revenue Code.[18]

Eligible training activities include employer-provided training that leads to an industry-recognized credential, or training programs authorized under the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act.[19] There may be examples of employer-provided training that do not result in a recognized credential for the employee but are beneficial to the company and the employee. Policymakers should explore expanding the universe of eligible expenses to cover additional forms of training even if a credential is not the end result of the training.

Finally, in order to incentivize both small and large employers, our proposal borrows from the modification to the R&D credit that allows small and new businesses to access the credit.[20] First, small businesses with gross receipts under $5 million in the taxable year and no older than five years would be allowed to use the Worker Training Tax Credit against their payroll tax liability. Small businesses could take this payroll tax credit up to five times, but the overall credit amount is capped at $250,000 in a given tax year.[21] Second, small businesses would be able to use the Worker Training Tax Credit against the Alternative Minimum Tax.[22]

Examples of Training Tax Incentives

Several states have provided businesses with tax incentives for training investments, including Connecticut, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, Rhode Island, and Virginia. These incentives range between 5 percent and 50 percent of training expenses.[23]

Worker training tax incentives can also be found internationally. For example, Austria provides a 120 percent business deduction for training expenses, as well as a 6 percent credit for companies that are not profitable enough to benefit from the deduction. France provides a business credit for entrepreneurs equal to the number of training hours multiplied by the minimum wage.

The European Union’s European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training looked at training tax incentives across Europe and found that these policies encouraged job training and required less administrative overhead than government programs.[24] Its report did caution that these incentives may subsidize training activities that would have otherwise been done anyway, and it recommends that incentives target populations that currently lack access to training. We believe that our policy design addresses both these concerns.

The Future of Work Initiative first proposed the Worker Training Tax Credit in May 2017, and since then, two bills have been introduced in the U.S. Congress that mirror this proposal. Senator Warner (D-VA) – along with Senators Casey (D-PA) and Stabenow (D-MI) – first introduced the Investing in American Workers Act in October 2017, and this past spring Representative Krishnamoorthi (D-IL) – along with Representatives Crowley (D-NY) and Sánchez (D-CA) – introduced a companion bill in the House.[25]

Other members of Congress have introduced similar bills. Representatives Pete Aguilar (D-CA) and Frank LoBiondo (R-NJ) introduced the On-the-Job Training Tax Credit Act of 2015, which would provide companies with 500 or fewer full-time employees a 50 percent tax credit to offset on-the-job employee training, up to $5,000.[26] And Representative Brenda Lawrence (D-MI) introduced the Promote Workforce Development for the Advancement of Manufacturers Act of 2017, which would allow manufacturing businesses to take a 20 percent credit for training expenses that exceed 50 percent of average over past 3 years.[27]

[1] While there is sufficient employee data to determine that training investments have fallen, the government has not surveyed employers since 1995 (in the now-discontinued Survey of Employer-Provided Training). Employer data is important to better understand types of training provided and levels of investment. In Toward a New Capitalism, we recommend a new, regular employer survey of training practices, including informal training. https://www.aspeninstitute.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/New_Capitalism_Policy_Agenda.pdf

[2] Mankiw, Gregory, David Romer, and David Weil. 1992. “A Contribution to the Empirics of Economic Growth.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 107, no. 2 (1992): 407-437. http://eml.berkeley.edu/~dromer/papers/MRW_QJE1992.pdf; Romer, Paul. 1990. “Human Capital And Growth: Theory and Evidence.” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 32 (1990): 251-286. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/016722319090028J; Lucas, Robert. 1988. “On the Mechanics of Economic Development.” Journal of Monetary Economics 22 (1988) 3-42. http://www.parisschoolofeconomics.eu/docs/darcillon-thibault/lucasmechanicseconomicgrowth.pdf

[3] Acemoglu, Daron, and Pischke, Jörn-Steffen. 1999. “Beyond Becker: Training in Imperfect Labour Markets.” The Economic Journal 109, no. 453 (1999): F112–F142. https://economics.mit.edu/files/3810; Brynjolfsson, Erik, and Andrew McAfee. 2012. “Thriving in the Automated Economy.” World Future Society. http://ebusiness.mit.edu/erik/MA2012_Brynjolfsson_McAfee.pdf.

[4] Economic Policy Institute. 2018. “State of Working America Data Library, College Wage Premium.” March 1. https://www.epi.org/data/#/?subject=wagegap-coll.

[5] Backes, Benjamin, Harry J. Holzer, and Erin Dunlop Velez. 2014. “Is It Worth It? Postsecondary Education and Labor Market Outcomes for the Disadvantaged.” IZA Discussion Paper 8474, Institute for the Study of Labor. September. https://www.iza.org/de/publications/dp/8474/is-it-worth-it-postsecondary-education-and-labor-market-outcomes-for-the-disadvantaged.

[6] World Economic Forum. 2016. “The Future of Jobs: Employment, Skills and Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution.” January. http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_FOJ_Executive_Summary_Jobs.pdf

[7] Dimon, Jamie. 2017. “2016 Letter to Shareholders.” JPMorgan Chase. April 4. https://www.jpmorganchase.com/corporate/investor-relations/document/ar2016-ceolettershareholders.pdf; Rometty, Ginni. 2016. “IBM CEO Ginni Rometty’s Letter to the U.S. President-Elect.” International Business Machines Corporation. November 15. https://www.ibm.com/blogs/policy/ibm-ceo-ginni-romettys-letter-u-s-president-elect/; Immelt, Jeffrey. 2017. “Competing For the World.” General Electric. May 4. http://www.gereports.com/competing-for-the-world/; Cohen, Patricia. 2017. “Jobless Rate at 10-Year Low as Hiring Grows and Wages Rise.” New York Times. May 5. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/05/business/economy/jobs-report-unemployment.html.

[8] Thrush, Glenn. 2018. “Amid Worker Shortage, Trump Signs Job Training Order.” New York Times. July 19. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/07/19/us/politics/trump-worker-training.html.

[9] Council of Economic Advisors. 2015. “Economic Report of the President.” https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/docs/cea_2015_erp_complete.pdf. More recent data on employer-provided training has been mixed. Data from the Society for Human Resource Management suggests that employer-provided tuition assistance has been falling in recent years, from 66 percent of surveyed businesses offering tuition assistance benefits in 2008 down to 53 percent in 2017. Meanwhile, data from the Association for Training & Development suggests that employer training investments have been roughly flat over the last decade. Society for Human Resource Management. 2017. “2017 Employee Benefits: Remaining Competitive in a Challenging Talent Marketplace.” https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/trends-and-forecasting/research-and-surveys/Documents/2017%20Employee%20Benefits%20Report.pdf. Association for Talent Development. 2017. “2017 State of the Industry.” December. https://www.td.org/research-reports/2017-state-of-the-industry.

[10] Waddoups, C. Jeffrey. 2016. “Did Employers in the United States Back Away from Skills Training during the Early 2000s?” ILR Review 69, no. 2 (March): 405-434. http://ilr.sagepub.com/content/69/2/405.

[11] Executive Office of the President. 2016. “Artificial Intelligence, Automation, and the Economy.” December. https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/documents/Artificial-Intelligence-Automation-Economy.PDF

[12] Hollister, Matissa, and Kristin Smith. 2014. “Unmasking the Conflicting Trends in Job Tenure by Gender in the United States, 1983–2008.” American Sociological Review, 79, no. 1, 159–181. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0003122413514584.

[13] The Economist. 2017. “Equipping people to stay ahead of technological change.” January 14. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2017/01/14/equipping-people-to-stay-ahead-of-technological-change.

[14] Lynch, Lisa. 2005. “Development Intermediaries and the Training of Low-Wage Workers.” National Bureau of Economic Research. http://www.nber.org/chapters/c9959.

[15] Waddoups, C. Jeffrey. 2016. “Did Employers in the United States Back Away from Skills Training during the Early 2000s?” ILR Review 69, no. 2 (March): 405-434. http://ilr.sagepub.com/content/69/2/405.

[16] Levine, Jonathan, Mark Popovich, and Tom Strong. 2013. “Doing Well and Doing Good: Pioneer Employers Discover Profits and Deliver Opportunity for Frontline Workers. The Hitachi Foundation. September. https://www.issuelab.org/resources/15753/15753.pdf.

[17] Adjusted for inflation (CPI-U)

[18] This concept is found in Section 414(q) of the federal tax code. It was set at $120,000 in total compensation in 2016. https://www.irs.gov/retirement-plans/plan-participant-employee/definitions.

[19] Section 3(52) of Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act defines an industry-recognized credential as consisting of “an industry-recognized certificate or certification, a certificate of completion of an apprenticeship, a license recognized by the State involved or Federal Government, or an associate or baccalaureate degree.”

Section 122(a)(2) of the Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act defines an eligible training provider as (A) an institution of higher education that provides a program that leads to a recognized postsecondary credential; (B) an entity that carries out apprenticeship programs; or (C) another public or private provider of a program of training services, which may include joint labor-management organizations, and eligible providers of adult education and literacy activities if such activities are provided in combination with occupational skills training.

[20] Office of Senator Christopher Coons. 2015. “Senator Coons’ R&D provisions included in year-end tax extenders bill.” December 16. https://www.coons.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/senator-coons-r-and-d-provisions-included-in-year-end-tax-extenders-bill.

[21] This provision should have no impact on the Social Security trust fund or individual worker contributions.

[22] The recent Tax Cut and Jobs Act of 2017 eliminated the Corporate AMT and raised the threshold — but did not eliminate — the AMT for individuals and pass-through businesses.

[23] Connecticut: Credit of 5% of all expenses incurred for the enhancement of human capital. An evaluation by Connecticut’s Department of Economic and Community Development found that the credit “produces modest and positive benefits… [including] cumulative productivity gains to firms making investment in human capital.” Department of Economic and Community Development. 2014. “An Assessment of Connecticut’s Tax Credit and Abatement Programs .” State of Connecticut. September. http://www.ct.gov/ecd/lib/ecd/decd_sb_501_sec_27_report_revised_2013_final.pdf.

Georgia: Tax credit of 50% of a company’s direct training expenses, with up to $500 credit per full-time employee, per training program. Maximum annual credit per employee of $1,250.

Kentucky: Tax credit of up to 50% of eligible training.

Mississippi: Tax credit of 50% of costs for training an employee, not to exceed $2,500 per employee per year.

Rhode Island: Tax credit of 50% of training expenses for all employees, capped at $5,000 per employee.

Virginia: Tax credit of 30% of training costs (if through community college) or $200 annually (if through private schooling) for employers who participate in worker retraining efforts.

[24] Cedefop Panorama Series. 2009. “Using Tax Incentives to Promote Education and Training.” European Centre for the Development of Vocational Training, Office for Official Publications of the European Committees. http://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/publications-and-resources/publications/5180.

[25] “S.2048 – Investing in American Workers Act.” 115th Congress. Introduced October 31, 2017. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/2048.

“H.R.5516: Investing in American Workers Act.” 115th Congress. Introduced April 13, 2018. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/5516.

[26] Companies with 500 or fewer full-time employees that also participate in on-the-job employee training would receive the lesser of the following as a tax credit: 50 percent of all expenditures for the job training program or $5,000. Representative Aguilar introduced the bill on May 19, 2015 to the House. https://www.congress.gov/bill/114th-congress/house-bill/2431.

[27] Representative Lawrence introduced the Promote Workforce Development for the Advancement of Manufacturers Act of 2017 on January 10, 2017 to the House. https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/house-bill/419.

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible in part by a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.